Peaking behind the mirror: tracking the similarities & differences between Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques and Hitchcock’s Psycho

Les Diaboliques is a 1955 French, black and white thriller, and its title is roughly translated as The Devils or The Fiends, as directed by filmmaker Henri-Georges Clouzot. The film holds a 98% approval rating based on 23 reviews on the Rotten Tomatoes website, and Time Magazine placed it on its top 24 horror films of all time list. In addition, Les Diaboliques holds a spot on Bravo Television’s top 100 films list. By comparison, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho developed and cemented many staples of the contemporary horror and slasher film genre, which are still in use by filmmakers today. Psycho was preserved by the Library of Congress at the National Film Registry. And like Les Diaboliques, Psycho also holds a place on the Bravo Television Network’s list of the top 100 scariest movie moments; while Entertainment Weekly and Premiere magazines both listed Psycho on their lists of the top 100 movies of all time. Psycho also holds a number of spots on a variety of The American Film Institute’s best of lists, including the coveted spot as the number one thriller of all time on its 100 Years, 100 Thrillers list; as well as the eighteenth position on the 100 Years, 100 Movies list. Finally, actor Anthony Perkins’s character, Norman Bates, holds the number two position on The American Film Institute’s 100 Years, 100 Villians list (beat out by Anthony Hopkin’s character of Hannibal Lecter from 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs). This essay will examine the ties between these two classic films, including an overview of what formal elements they have in common; as well as an examination of what areas Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques may have influenced Hitchcock’s Psycho. To this end, we can ask what do these two films have in common? Both films are adaptations of fiction novels. Both films were made unconventionally, outside of the norms of the conventional studio system. Both films also share similar narrative structures with a number of plot twists occurring over the course of their story arcs (including scenes where the main characters are murdered in bathrooms early on in the story). On a formal level, both films were shot in black and white; and both films explored similar themes and ideas as revealed through a carefully crafted mis-en-scène. Finally, both films were producers of a time in filmmaking where the best directors worked to push the boundaries of their craft.

Both Les Diaboliques and Psycho are adaptations of fiction novels. Les Diaboliques was adapted by screenwriters Henri-Georges Clouzot, Jérôme Géronimi, René Masson, and Frédéric Grendel from the novel Celle qui n’était plus (She Who Was No More) by the French crime-writing duo of Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. In fact, there seemed to have been a bit of a friendly competition in acquiring the rights to Celle qui n’était plus, rights which Hitchcock saw as important to acquiring as he felt the story would help him push his own filmmaking craft. Film critic Terrance Rafferty, in his essay Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts revealed that “…Hitchcock, who had once toyed with the idea of filming the story himself, was an admirer…” (Rafferty). Furthermore, Kim Newman, in an interview appearing on the Criterion Blu-Ray release of Les Diaboliques also noted how:

Hitchcock saw (Clouzot) as a challenge (to his own style of filmmaking), and apparently wanted to buy the book, (but when he couldn’t) he bought the authors next book (which he made into Vertigo). Vertigo was his attempt to do something bigger, and better, and more colourful, and richer, and deeper, than Diaboliques. Although we now hail it as a masterpiece, it was commercially not a huge success and critically was not much liked. And so he may have felt that Clouzot had beaten him. And you have the feeling that for a good five to ten years he had Diaboliques in his mind. And I think that there was a certain frustration that he couldn’t make a film like that because he was working in America and he had missed the boat… And so, he turned around and made Psycho, which temporarily blots out the reputation of Diaboliques (Newman).

Psycho was also based on a novel, of the same name, as written by Robert Bloch. Bloch based his novel on the case of convicted Wisconsin serial murderer Edward Gein (whose story also influenced the 1974 slasher film, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, co-written and directed by Tobe Hooper, as well as the 1991 psychological horror film, Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs). Bloch too was influenced by Les Diaboliques, stating in a 1983 interview that, “…yes! In fact my favorite horror film of all time is Diabolique. I think that is the epitome of what the horror film should bee. You'll note that there is very little bloodshed” (Lofficier). Finally, Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan, in his book, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light notes how: “…Hitchcock had described Psycho to the New York Times as a story in ‘…the Diaboliques genre’” (McGilligan).

When Psycho was made, Hitchcock was at the peak in his career, fitting the true definition of ‘auteur,’ as film historian Stephen Rebello described how usually: “Paramount gave Hitchcock carte Blanche over story selection, screenwriter, casting, editing, and publicity for any project costing $3 million or less” (Rebello 15). But in spite of this clout, the studio was nervous about making Psycho. Rebello reveals how Paramount executives responded to the film’s script as being: “Too repulsive… rather shocking… cleverly plotted, quite scary toward the end, and actually fairly believable… But impossible for film” (13). Ultimately, Hitchcock would move outside the norms of the conventional studio system and finance the project himself, as professor-journalist Joseph W. Smith describes in his book, The Psycho File:

In a rare move, the fiscally conservative Hitchcock decided to finance the picture himself - and to film it at Universal, if Paramount would distribute it. Hitchcock deferred his usual $250,000 director’s fee in exchange for an initial 60 percent ownership and a deal in which all rights and revenues would revert to him after a predetermined profit for Paramount. According to biographer Donald Spoto, this savvy deal eventually made Hitchcock a millionaire 20 times over (Smith 14).

In terms of narrative, both films share a similar structure and both feature a number of plot twists over the course of their overall story arc. Clouzot sets up the first half of Les Diaboliques to concentrate on the exploration of the relationship between the film’s protagonists, Christina (Vera Clouzot) and Michel Delasalle (Paul Meurisse) and Michel’s mistress, Nicole Horner (Simone Signoret). Michel is the dictatorial director of a dilapidated countryside boarding school who inflicts metal and verbal abuse not only upon his students and staff but on his wife Christina as well. Christina is a good, kind hearted, and god fearing woman who appears to be very much helpless in her situation even though she does hold the balance of power in her relationship with Michel: she is the wealthy owner of the school itself. But she is unable to leave him, even though he is having an affair with another teacher, Nicole. And as Christina already knows, Nicole soon learns that no one is prone from Michels wrath. So, the two female protagonists work out a plan to murder Michel. From this angle, Les Diaboliques shares a parallel with another Hitchcock film, 1951’s Strangers on a Train, as both stories revolve around protagonists who appear to join forces to commit murder most horrid. The first half of Clouzot’s film is also similar to Hitchcock’s Psycho, as Les Diaboliques in that it ends with the murder of Michel in a bathtub by Christina and Nicole. Like Psycho, where main character of Marion Crane is brutally stabbed to death while taking a shower by an unknown assailant (possibly Norman Bates’s mother), the murder Michel also takes place early on in the film, but unlike Psycho, it is not an unexpected murder. Christina and Nicole bring the body back to the school and dump the body into a murkily neglected swimming pool where the protagonists hope the boy will be found and chalked up to an accidental drowning. However, when the pool is eventually drained, the body has disappeared. This twist allows Clouzot to rack up the tension with each scene that follows during the second half of his film, as the audience wonders what will happen to the protagonists. Has Michel come back from the grave? Is someone trying to coerce and deceive the protagonists? Or did the protagonists do something else that’s wrong? These questions ultimately leads up to some of the biggest twists Clouzot has in his film, one of which sees Michel, seemingly back from the grave, trying to kill Christine in the bathroom. It’s a scene that holds as much power as Hitchcock’s shower scene in Psycho does, in that Michel’s appearance and Christine’s subsequent death is completely unexpected. Newman notes how this scene would be remembered equally alongside Hitchcock’s shower scene, noting how it would “…stay in people’s heads for decades… it became one of those films that became a part of popular culture” (Newman).

Artifact 01 > Clouzot, Henri-Georges. Criterion Collection’s DIABOLIQUE Blu-Ray Cover. Criterion, 2011.

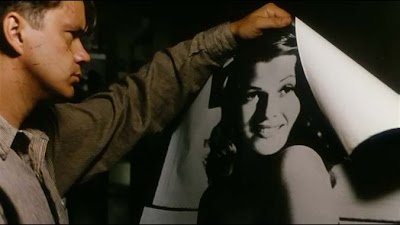

In Psycho, Hitchcock introduces us to Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) and Sam Loomis (John Gavin), two lovers who yearn to get married but are not in a sound financial position to do so. Marion, feeling trapped by her ordinary existence, seizes an opportunity to steal $40,000 from her employer. Hitchcock’s camera skillfully follows Marion as she escapes her life, intending to join Sam for a life together in California. En route, a heavy rainstorm sidetracks Marion, who ends up driving lost off the main highway, eventually turning into a lonely looking motel, the Bates Motel, where she decides to seek refuge at until the storm passes. There she meets Norman Bates, the manager of the motel, who tells her that’s he rarely has customers anymore because of his location off of an old highway, long forgotten by a new highway that replaced it. He explains how he lives with his mother in a house behind the motel, and he invites Marion to have dinner with him. As she unpacks her things, she overhears an argument between Norman and his mother about his interest in her, their voices carried down over a hill through the damp night air, and into her motel room’s open window. Marion settles into her room, carefully unpacking a few of her things, and wrapping the cash she stole inside a newspaper she places on the bedroom nightstand. She then sits, carefully considering what she has done, calculating what she might need to do to pay her boss the money she has spent from what she stole. She then enters the bathroom, tearing up and flushing the piece of paper she’s done some math on, and enters the washroom’s shower. This is one of cinema’s most famous scenes occurs, with the very unexpected murder of Marion by, the audience suspects, Norman’s mother. Unlike the washroom murder in Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques, this murder is not at all anticipated or expected by Hitchcock’s Psycho. It’s a scene that marks a significant shift in the film’s narrative, moving the focus of Psycho from following protagonist Marion Crane to Norman Bates, who appears to be covering up a murder committed by his elderly mother. Other than the strange argument between Norman and his mother that occurred mere moments before, there are no scenes of anyone plotting to kill Marion as Christina and Nicole do in Les Diaboliques. It’s a monumental plot twist that Hitchcock serves his audience, very early in his film’s narrative. By contrast, Clouzot places his film’s unexpected murder in a more traditional place in his film, near the climax of the narrative, as opposed to early on in Les Diaboliques. And from the murder of Marion Crane onward, the second half of Psycho would present a number of mysteries and more shocking twists as the remaining characters feel their way through to the conclusion of Psycho’s wildly twisting plot.

On a formal level, both Les Diaboliques and Psycho were shot in black and white by directors who both had a solidly thorough understanding of how to successfully work in black and white, at a time when filmmaking was gradually shifting from using black and white film to using colour stock. Today, very few filmmakers are able to work in black and white, primarily due to the Hollywood studio system’s belief that black and white films are too hard to market, and simply do not have a large enough appeal to turn a profit with audiences. Indeed, these same concerns existed as a very real challenge back in the 1950s, further complicated by the introduction of television into the home of movie-going audiences, marking an alternative use for their previously limited time and entertainment dollar. As such, today it appears that only those filmmakers who are at the very top of their game are able to use their clout in filming in this old style way. Woody Allen’s 1979 film, Manhattan was shot in black and white only after Allen achieved a high level of success with his Academy Award winning film, 1977’s Annie Hall. Martin Scorsese was able to make his 1980 film, Raging Bull, in black and white after the critical success of 1976’s Taxi Driver. There was also a more formal concern for Scorsese, who after screening prep-footage for the film, was told that the colour pallette of the film’s mis-en-scene didn’t match the reality of the 1940s and ‘50s that it was trying to depict, as noted by Peter Biskind in his book Easy Riders and Raging Bulls. Scorsese also felt that a black and white style would have more of “…a tabloid look, like (the photographs of) Weegee” (Biskind). Directors Steven Spielberg, and Tim Burton, were also ab le to shoot black and white films after achieving a high degree of both commercial and critical successes, with Spielberg’s 1993 film, Schindler’s List, and Burton’s 1994 film, Ed Wood. Finally, Joel and Ethan Cohen were able to make a neo-noir feature film in 2001 with The Man Who Wasn’t There, after achieving critical and box office success with films such as 1996’s Fargo.

Working in France, Henri-Georges Clouzot likely faced less pressure to shoot in colour as directors in the European film system had much more creative freedom than directors in Hollywood. Clouzot shot his most famous films in black and white, including 1947’s Quai des Orfèvres and 1953’s Le Salaire de la peur (The Wages of Fear). But the choice may have gone beyond what was available aesthetically. In post-war Europe, movie equipment, film stock, and other supplies were often difficult to come by, so it is reasonable to assume that Clouzot simply used what was most readily available to him from film to film. Like Hitchcock, Clouzot had a relatively early exposure to films, as well as a relatively early start in filmmaking as a profession. In the 1930s, Clouzot worked in Germany writing and translating scripts and dialogue across over twenty different films. He was also able to study the films of F.W. Murnau and Fritz Lang, whose German expressionist style and lighting would influence Clouzot’s own later work in films such as Les Diaboliques. But in the studio system of the late 1950s, it is likely that Hitchcock faced pressure to shoot Psycho in colour, as Hitchcock ahd already made a large number of successful colour films for the Hollywood system (such as, but not limited to: 1948’s Rope; 1954’s Dial ‘M’ for Murder which was not only shot in colour, but in 3D as well, and Rear Window; as well as 1959’s North by Northwest). Drawing a parallel to the film noir movies of the 1940s and ‘50s, in his book The Psycho File, Joseph W. Smith describes other motivations for Hitchcock’s decision to film Psycho in black and white:

Not only was this cheaper, but he also felt that red gore would be too repulsive for his viewers… Budget constraints aside, Psycho’s black and white photography greatly enhances its chilling and depressing effect and perfectly matches its sordid, seedy milieu of cheap motels, used car lots, and low-paying jobs… Psycho is not (a world) we would ever want to live in (19).

Smith’s quote perfectly illustrates Hitchcock’s keen understanding of the power of film and how different formal choices impacts an audience’s overall emotional experience of what they are observing on screen. This was a skill that Hitchcock refined over the course of a lifetime, and in a famous interview with film critic and French New Wave filmmaker François Truffaut, Hitchcock described some of his own early film influences as an impressionable young man in Britain:

Though I went to the theatre very often, I preferred the movies and was more attracted to American films than to the British. I saw the pictures of Chaplin, Griffith… I especially remember Intolerance and The Birth of a Nation… all the Paramount Famous Players pictures, Buster Keaton, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, as well as the German films of Decla-Bioscop, the company that preceded UFA. Murnau worked for them (Truffaut 26).

Chaplin, Griffith, Keaton, and Murnau were all very accomplished black and white, silent film storytellers. All of their films were very visual, utilizing the power of black and white filmmaking to enhance their stories and their film’s mis-en-scene. The creativity these directors infused into their work ensured that they didn’t have to rely on title cards as a crutch for telling their stories to audiences. These directors knew their audiences would be smart enough to follow the story based on the visual cues given to them from scene to scene. And in watching the films of both Clouzot and Hitchcock, one can readily see how they learned from those early filmmakers. In support of this line of thought, Hitchcock discussed with Truffaut how, at a very young age, he was very much a student of the technical aspects of filmmaking as storytelling tools, stating how:

I was very much aware of the superiority of the photography in American movies to that of the British films. At eighteen I was studying photography, just as a hobby. I had noticed, for instance, that the Americans always tried to separate the image from the background with backlights, whereas in the British films the image melted into the background. There was no separation, no relief (31).

The progression of Hitchcock’s own career in filmmaking started when he first designed title cards, and then worked as an art director for silent movies in the early 1920s before working his way up to the director’s chair in 1922. Hitchcock would go on to direct a dozen silent films and thirty sound films which were all shot in black and white before he directed his first colour film, 1948’s Rope, starring James Stewart. But again, it seems that the decision to shoot Psycho in black and white may have been tied to Hitchcock’s appreciation of Les Diahboliques’s style and look. As discussed earlier in this essay, Joseph W. Smith confirms how Hitchcock: “…appears to have been rankled by the success of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diboliques” (Smith 18). Furthermore, Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan, in his book Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light notes how Hitchcock:

…told (Psycho screenwriter Joseph) Stefani that the French film had influenced his decision to shoot Psycho in black and white… Their afternoon meetings were leavened by screenings; and Diabolique was shown more than once to Stefano and others on the staff (McGilligan 583).

One can see the similarities of the mis-en-scene as constructed in both Les Diaboliques and Psycho by examining each film’s opening moments. Les Diaboliques opens with Georges Van Parys’s very ominous score playing as the credits roll over an abstracted image that could be water on a pond, or on a wet sidewalk (later in the film, the viewer will be able to connect this opening image as being of the school’s swimming pool). Water is usually equated to life, but in Clouzot’s crafter world, water as the power to kill people, and can often appear as murky, and very dirty. The names of the film’s stars appear in strong capital case letters, with the title of the film itself appearing in similar lettering, only in smaller case letters. At approximately 1:20s, children sing a lonesome, aching melody that could easily be a requiem mass for the dead. The simple opening scene nicely represents the kind of story Clouzot will tell, as it leaves a viewer in a state of unease and suspense, wondering what they are about to experience. As the music comes to an end, the image dissolves into that of a car driving from the city to the country side, arriving at a rather dilapidated looking boarding school. It’s the last time that music will play, only the diegetic sounds of the characters and their surroundings will be played for Clouzot’s audience, grounding both them and the audience in the film’s reality. The car we see drives up to a large iron gates, above which is a large sign declaring the name of the school - Institution Delasselle. As a man drives into the school grounds, we hear him being addressed by another character, and we learn that this is Michel Delasselle, the director of the institution that also bears his name. With these simple shots, Clouzot is taking the viewer from the outside world into the world the characters of his film will inhabit at the boarding school. In many ways, the boarding school is a prison for its characters, as emphasized by the large iron gates and the solid brick wall that surrounds the school.

Michel Delasselle, the director of the school is driving the car we see,

Works Cited

Lofficier, Randy and Jean-Marc. “Interview with Robert Bloch.” The Unofficial Robert Bloch Website [L’Ecran Fantastique (1983) and Starlog #112 (1986)]. https://web.archive.org/web/20150212121219/http://mgpfeff.home.sprynet.com/lofficier_interview1.html

McGilligan, Patrick. Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light. New York: ReganBooks / HarperCollins Publishers, 2003.

Newman, Kim. “Novelist and Film Critic Kim Newman Discusses Les Diaboliques.” Interview. Les Diaboliques. New York: Criterion. Blu-Ray Supplement, 2011.

Rafferty, Terrance. “Diaboliques: Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts.” The Criterion Collection. Criterion, 16 May 2011. Web. 25 Nov 2011. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1859-diabolique-murder-considered-as-one-of-the-fine-arts

Robello, Stephen. Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. England: Marion Boyars, 1990.

Smith, Joseph W. The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock’s Classic Shocker. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009.

Truffaut, Francois. Hitchcock / Truffaut: The Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1983.