“Exploring Urban Identities through Photography as a Fine Art Medium”

An online course through BAI by Niklas Goldbach

I took this course in the fall of 2024, as it appealed to my interest in further exploring how individuals and artists represent their environments, as well as themselves and other people in the photographs of cities that they take. Specifically, the course website states:

“This course delves into the complexities of urban landscapes and their unique identities through photography. In four weeks, you’ll get an introduction how to capture diverse aspects of a city, including its people and culture. Using your camera as a tool, we’ll cover various techniques and approaches to photography, emphasising its artistic potential in telling stories, following conceptual approaches, and capturing the distinctive visual characteristics of urban spaces.

In the first part of the course, we’ll explore how man-made environments shape and reflect the social, cultural, and historical contexts of a city. We’ll investigate the ways in which different neighbourhoods and communities have their own distinct identities, and how they are communicated through architecture, public spaces and other urban features. We will discuss the different sub-genres and approaches of photography which often overlap: street photography, documentary photography and architectural photography.

In the second part of the course, we’ll examine the role of identity politics in photography and how photographers can use their art to engage with social and political issues. We’ll look at the work of photographers and artists who have used their camera to challenge dominant narratives or amplified the voices of marginalised communities. You’ll have the opportunity to use your own photography to explore issues and aspects of identity and representation, and develop ideas how to contribute to the ongoing dialogue about the role of art and photography in shaping our understanding of the world around us.”

This blog will serve as a repository for notes I take during the course, as well as other written reflections and course-related projects I create.

COURSE OVERVIEW

This course will examine several ideas about:

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY: where photographers can showcase a city’s energy itself through the art of street photography - examining people and the spaces they move through;

ARCHITECTURAL (CITYSCAPES) PHOTOGRAPHY: where one learns how to examine architecture (cityscapes) photography;

DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY: where, in addition, one can ask if the idea of documentary photography can really exist, and what it actually is (a focus on communities, urban life, neighbourhoods, gentrification, older buildings falling apart, new buildings, social & cultural aspects of cities and environments, peoples - class, race, gender - power dynamics of who holds the power); and

ABSTRACTION: can help challenge a viewer’s perception of the urban environment - abstract perception allows for creative interpretations of our environments (experiment with angles, reflections, atmosphere).

Weekly projects build upon each other and work towards the final project.

Introductions

It wasn’t required, but I created a post in the forums introducing myself to my classmates.

I’m Steven Lee, a third year bachelor of fine art student at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, in the city of Surrey, British Columbia. I live not far from my campus, in South Surrey. I’m a 10 minute drive from the border with Washington State, and a 40-60 minute drive southeast of downtown Vancouver

I was born in the small city of Williams Lake, which is about a 7 hour drive northeast of Vancouver. It’s a very rural landscape, a small valley town surrounded by Coniferous trees and the odd Deciduous ones too, a city that feels like a throwback to a simpler, slower time that was never ruled by our contemporary screen culture. It’s a place that’s embedded into my very being.

When I was 13, my parents retired to South Surrey where I went to high school. In the 1990s, the area still felt a bit more rustically rural and removed from the sleeping giant of Vancouver, a place that artist-writer Douglas Coupland would eventually call a “city of glass.” The year I finished high school was when my Dad announced that he wanted us to move from the house we’d settled into in Surrey to a condo overlooking the Port of Vancouver in downtown Vancouver about twenty years ago now.

I didn’t want to move. Vancouver, for me, was more of a place you visited as opposed to a place where one could live. Its urban reflections stood in sharp contrast to the rural references and comforts of my younger years. But I layer that Vancouver did offer a closer connection to other things I was interested in: cycling; flâneuring; going to art galleries; heading to local festivals such as the Vancouver Film Festival, the Vancouver Fringe Festival, and the Vancouver Writers Festival; seeing movies on the big screen; walking to the places I bought groceries from; and walking nude from Acadia to Wreck Beach several times each summer.

Ultimately, I was fortunate enough to live with my parents downtown for just over twelve years. If I could have afforded it, I might have stayed downtown. But eventually I was able to get a place in South Surrey again, a detached townhouse big enough to live in, as I finished my BFA, and started my independent studio practice. The place has a small space I use as a studio where I draw, paint, photograph, and make mixed media artwork. And my garage has a small space I’ve setup for working on sculpture pieces, primarily with wood.

The South Surrey of my teenage years and my adult ones has many stark differences. Each week, it feels as if another acre of land is being bulldozed for a new glass tower, townhome complex, or strip mall. For a time, I tried documenting the change, but the rate un which the changes occur becomes almost mind bogglingly difficult to measure and record. There’s an insane busyness to Metro Vancouver by day, and a loneliness that echos the film noir of the 1940s and 50s by night.

In recent years my artistic practice has changed focus to something more personal - portrayals or the self. You can find me online on social media through my website: www.stevelee.art.

Artifact 01 > Steven Hanju Lee. “then & now 2: yesterday.” 35mm black & white film photography, Late 1990s.

Artifact 02 > Steven Hanju Lee. “COMPARISONS PROJECT: VANCOUVER. ‘FADED PLACES.’” 20” x 28” daytime digital long exposure, 23 Feb 2019.

Artifact 03 > Steven Hanju Lee. “Abandoned Toy.” Apple iPhone 11 Pro Digital photograph, 26 Sep 2020.

Artifact 04 > Steven Hanju Lee. “Casting Long Shadows Upon the Horizon.” Apple iPhone 11 Pro digital photograph, 12 Apr 2024.

Artifact 05 > Steven Hanju Lee. “The claustrophobia of depression.” (Draft 1) Apple iPhone 11 Pro Digital photographic joiner collage, 07 Oct 2024.

Notes - WEEK 01 > TO THE STREET

TIME - we freeze time but can take time to photograph something that makes sense… often we have to return to a place to develop a sense for why you want to photograph it. The time of day can impact things too.

Street photography doesn’t always has to take place on the street. It can take place in their everyday environment. This can require patience and bravery.

ARTICLES ON PHOTOGRAPHIC SEEING

Coppieters, Chris. “Analyzing a Photograph: A How-To Guide.” University of Oregon, 1995.

Studio Nuovo. “Basic Strategies in Reading Photographs.” 2024.

KEYWORKS

1) Nicèphore Nièpce, “View from the Window at Le Gras.” 1822-27.

In her Udemy course, THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY (1839-1930s), Kristen Hutchinson describes this photograph as being the earliest surviving photograph (and possibly the first photograph ever taken).

Artifact 06 > Nicèphore Nièpce. “View from the Window at Le Gras, Colour 2020.” Jonnychiwa, 3 Apr 2020.

Artifact 07 > Nicèphore Nièpce. “A View from the Window at Le Gras.”

Artifact 07 > Nicèphore Nièpce. “A View from the Window at Le Gras.”

Artifact 08 > Nicèphore Nièpce. “A View from the Window at Le Gras.”

FORM

With Niépce’s heliograph, it is known that the image was captured with a camera obscura, with the scene reflected onto a 16.2cm x 20.2cm (6.4” x 8.0”) chemically coated, light sensitive, metal plate. This black and white art object was directly captured onto a fixed surface, so unlike the development of glass plates and film negatives, there is only one final art object that exists for this work - no copies can be made from the original as can be done with printmaking or photographic processes that had yet to be developed.

Specifically, as noted by Todd Vorenkamp, in his 2021 article for B&H Photo titled Elements of a Photograph: Form…

“…there are seven basic elements of photographic art: line, shape, form, texture, colour, size, and depth.”

There are many lines in this old, faded fixed plate image. First, there are numerous lines in Nièpce’s image which serve as leading lines which guide the viewer’s eyes deeper and deeper into the image, as illustrated in Artifact 09 below. There are other lines that break up the image further - lines which form the various geometric shapes (assorted squares, rectangles, and other curvilinear shapes) of the buildings, windows, and doors of the image. Finally, there are lines that divide the scene into its varied layers of depth, as illustrated in Artifact 10 below.

Artifact 09 > Leading lines in A View from the window at Le Grass.

Form

The Merriam-Webster definition of “texture” that we, as photographic artists, are concerned with is: “…the visual or tactile surface characteristics and appearance of something.” Nièpce’s photo has a number of textures, ranging from smooth to rough. The windows, the sides of buildings, and the sky have a nice, smooth surface appearance to them. This is in contrast to the rough look of the tiled roof of the central building, and the leafy darkness of the tree that sits in front of the large, clear sky.

In terms of colour, although different people have colourized Nièpce’s photograph (as shown in Artifacts 06, 08, 09, and 10), the original image was in black & white, a constraint placed upon inventors of the day by the simple fact that colourized film processes had not been discovered & invented yet.

The image Nièpce created here has at least seven layers of depth, as seen in Artifact 09 below. In the foreground, the image is framed by two open windows, and the camera sits just in front of this window, inside a room on the second storey of a building on Nièpce’s property. To the immediate right of the window is a taller building with a door at its bottom that leads to a path, forming a second layer of depth in the image. The third layer features the mid-ground of the image with its bulky, prominently centred building with a sloped rectangular shaped roof, its two long parallel sides leading the viewer’s eye towards the background. On a fourth layer, one sees another taller building, just to the left and behind the prominently featured, centred building. A fifth layer is a tree just behind the tall building of the fourth layer. Then, a field can be seen on the sixth layer, and behind that, on the image’s seventh layer of depth, the sky. All of these layers work together to create the illusion of a three dimensional image.

Artifact 10 > The Seven Layers of Depth in A View from the Window at Le Grass.

CONTENT

The story being told in A View from the Window at Le Grass is a simple one. You get the feeling that you are standing at this window, possibly after getting up from bed, looking out at the farm-like surroundings as the cool morning air comes in through the window you’ve just opened.

CONTEXT

Hutchinson also notes that Nièpce had found that the process of lithography was a limited way to produce images. As such he experimented with different ways to produce realistic images through the action of light on photo sensitive materials. The early days of photography was a time of experimentation and development to capture better images, at a faster rate, which were able to last longer as a fixed object. The process Nièpce’s photographic process was what he called HEILIOGRAPHY, from the Greek, meaning “sun writing.”

Hutchinson describes how, on a technical level, Nièpce placed a prepared plate in a camera obscura and exposed it from a window on his estate for a time that is believed to have lasted approximately eight hours (one photo historian has estimated that the exposure may have taken several days, a conclusion they came to after studying Nièpce’s notes and journals). Dr Belden-Adams, writing for SmartHistory, describes the process by explaining how:

“At a second-story window of his country house in Le Gras, France, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce placed a camera obscura, loaded with a polished, light-sensitive, bitumen-coated, pewter plate, and aimed it toward the view outside. He then uncovered the lens for anywhere from eight hours to “several days.” The result: the earliest surviving camera-made photograph.”

Hutchinson also describes how Niècpe’s photograph was similar to the paintings that were created by the Impressionists in the later 19th century as those painters felt they no longer had to strive to create hyper-realistic images in their paintings because of the advent of photography which was a tool that could produce the realistic images much better.

2) Louis Daguerre. “Boulevard du Temple.” 1837-39.

Works Cited

Belden-Adams, Kris. "Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, View from the Window at Le Gras.” Smarthistory, 11 July 2022, accessed 09 Oct 2024. https://smarthistory.org/joseph-nicephore-niepce-view-from-the-window-at-le-gras/.

Assignment 01 - Our House in the Middle of Our Street

Document the house (and the street ?) your are currently living in – your approach can be personal, poetic, analytical… it can be abstract, documentary or narrative. You can depict a micro- or a macro cosmos.

Reflect on artistic and formal strategies other photographers have used for their work – did you have an inspiration?

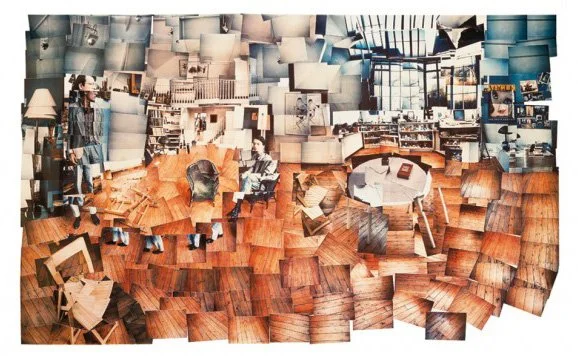

I’ve long been attracted to playing with multiple images that are shot, curated and arranged within the confines of a single space. The finished product forms a composition known as a joiner collage, a concept developed and refined by British pop artist David Hockney in the 1980s. Essie King, writing for MYARTBROKER.COM in her February 2024 essay entitled “Exploring David Hockney’s Joiners” explains how:

“This method, which involves piecing together a mosaic of photographs to form a cohesive image, challenges and transcends traditional perspectives in both photography and painting. By fragmenting and then reassembling the visual field, Hockney's joiners disrupt conventional viewpoints, inviting a deeper exploration into the intricacies of perception and representation.”

Hockney’s joiner style parallels his interests in drawing and painting. Hockney created his first collage by accident, when he photographed a living room that he was creating a painting of. Hockney took many photographs of the space and glued them together onto a surface with the intention of using the finished piece as a point of reference for his painting. On looking at the final composition, he realized it created a narrative, as if the viewer of the collage were able to move through the room.

Artifact xx > Hockney, David. “Living Room.”

Hockney’s joiners primarily play with the concept of how individuals see. The cubist paintings of Paul Cezanne, Georges Braque, and Pablo Picasso trace a line to the joiner collages of Hockney. Both cubism and joiner collages share the concept of analyzing a subject or a scene by breaking it up and reassembling it in an abstracted visual representation from multiple angles and perspectives. This abstraction plays a role in creating new meanings of the artwork. In a YouTube video by the Getty Museum called David Hockney’s Pearblossom Hwy, Hockney explains how:

“Although it looks as though there is a central viewpoint, not one photograph is taken from that central viewpoint, they’re all taken from all over. You’re looking down on the road, you’re looking up, you’re looking every direction… every photograph here is taken close to something which is why you the viewer feel involved in it, feel close to it. That’s what does it... you are actually, literally close to everything, you’re moving around in it… I was trying to pull you in.” Hockney also describing how: “…when I first did collages, I called it drawing with a camera, as I thought that’s what you were doing. In drawing, you make choices, but we don’t all see the same thing and we don’t all hear the same things either.”

Artifact xx > Hockney, David. Pearblossom Hwy.”

In another short video called David Hockney on his photocollage process (1983), by L.A. Louver (a gallery which represents Hockney), Hockney notes how: “…time was appearing in the picture, and because of it, the bigger illusion of space.” Variations in lighting, colour, textures, and viewpoint illustrates how time affects a space through the passage of time in joiner collages.

Works Cited

King, Essie. “Exploring David Hockney’s Joiners.” Myartbroker.com, 06 Feb 2024, accessed 14 Oct 2024. https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-david-hockney/articles/exploring-david-hockney's-joiners.

Getty Museum. “David Hockney’s Pearblossom Hwy.” YouTube, 01 Feb 2012.

L.A. Louver. “David Hockney on his photocollage process (1983). YouTube, 01 Apr 2020.

Create a series of (minumum) 3 – 5 (maximum) photographs. Reserve some time for selection process and give your series a title. Upload your results to the Forum and prepare a short presentation in which you explain your formal and artistic choices (artist’s statement).

Artifact xx > Lee, Steven. “Homescapes 1.” Digital Photographic Collage.

Homescape 1 is a digital photographic collage composed of approximately 30 different photos taken over two to three days between October 7-14, 2024. I shot most of the images at night, a period in which I often lay awake in bed thanks to the insomnia I suffer from. I shot the photos for this collage from two different perspectives. First, the top half of the photo consists of a variety of shots as seen from my perspective, as if the viewer were looking at the mess in the guest room at my mother’s house through my eyes. And the lower half of the photo shows my face, in a variety of distinct positions, mostly alone, and a few where I snuggled closely to my dog.

Artifact xx > Lee, Steven. “Homescapes 2.” Digital Photographic Collage.

Homescape 2 is a joiner collage composed of approximately 50 photos taken at four or five distinct times over the course of three or four days between October 8-14, 2024. I played a lot more with the passage of time in this collage, and with showing myself from different perspectives, doing different things. I also highlighted the mess of the guest bathroom at my mother’s house, which, like the guest room, has become so disarrayed thanks in part to my poor physical health since my stroke in January 2023, combined with the depression that so often paralyses me.

A PDF of this project can be viewed here.

Instructor’s Feedback…

“Glad you contextualized yourself within Hockney’s universe. Looking forward to your assignment next week!!” - Niklas Goldbach