Teaching with Themes

I originally wrote this for a peer reviewed COURSERA project in a workshop by the Museum at of Modern Art dealing with the topic about teaching art & ideas. This write-up is posted in the course mini-blog for week 5 but I liked the work I did on this and wanted to post it separately so I can share it more easily.

Part 3 - Peer Reviewed Assignment

Part One: Select Your Theme

Select a theme. You can choose a theme from the course or from MoMA Learning, or create your own. Remember that a good theme is a universal concept that can be explored on its own and is relevant to students’ lives. For example, Dada is an art movement, but Artistic Collaboration, which relates to Dada, could work as your theme.

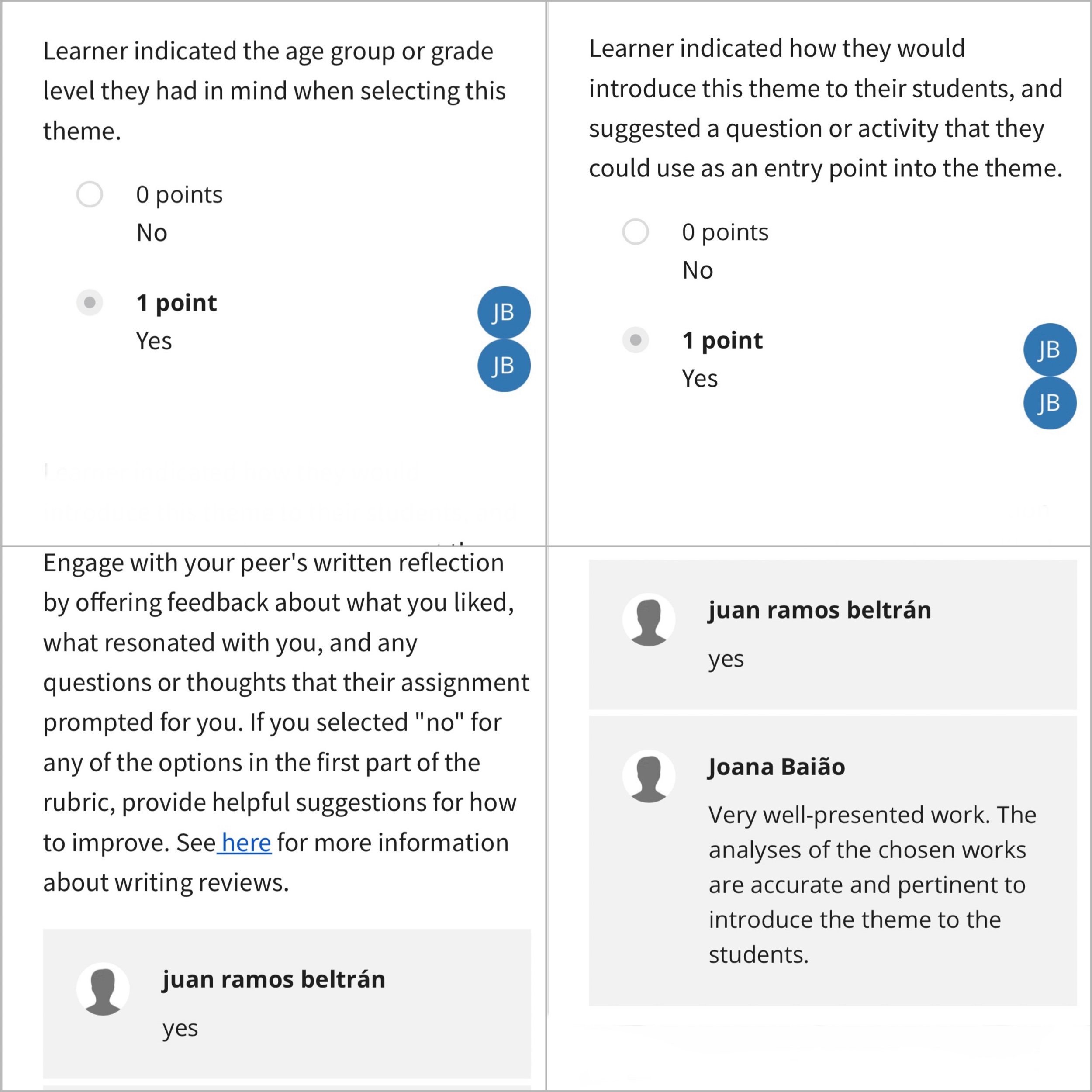

Test it through the Theme Machine. If your theme was not successful, choose another theme to test.

When you identify a theme that is successful in the Theme Machine, describe your theme in one sentence.

Topic: Depression, anxiety, and loneliness

Theme Statement: A central theme explored in the fine art photographs by artists Francesca Woodman, Eva Charkiewicz, Jackie Dives, and Janelia Mould is that major depressive disorder can destroy a person’s ability to concentrate, enjoy life, feel connected with others and good about themselves, sleep, and work.

Part Two: Select Your Artworks

Choose 2-4 works of art that have not been discussed in this course to explore in your theme. We encourage you to select works of art from a local museum or gallery. You can also select images from MoMA’s website or another museum website. For each work, indicate the title, artist(s), date, and medium by including this information with your submission or linking to the page about the work on a museum’s website.

Write 100-200 words about how the works of art connect to your theme.

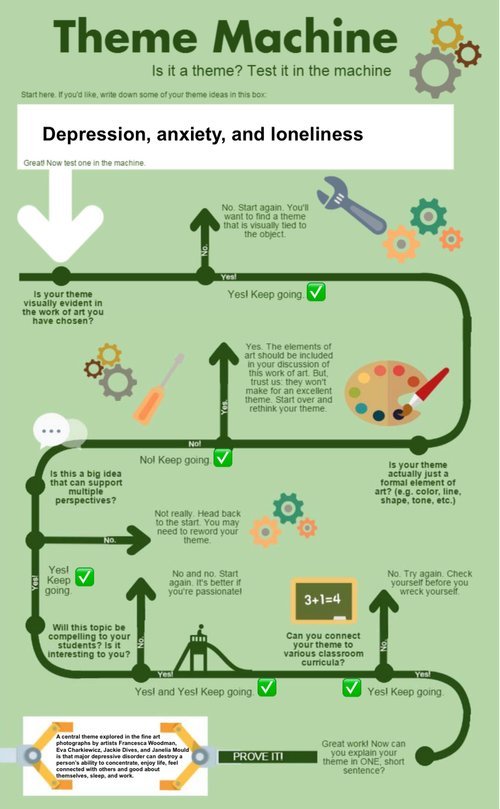

Francesca Woodman. “Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island.” Black & White Film Photograph. 1976.

Francesca Woodman’s work explores many themes related to anxiety, identity, depression, and loneliness, often through a surrealist black and white lens which helps to give her film photographs a timeless quality (surrealist art is marked by the intense unbelievable, fantastical, and irrational reality of a dream. Specifically, the Tate notes how: “It balances a rational vision of life with one that asserts the power of the unconscious and dreams. The movement's artists find magic and strange beauty in the unexpected and the uncanny, the disregarded and the unconventional”).

In “Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island, 1976,” Woodman presents herself as a solitary figure in a sparse, forgotten and desperate space. The camera is also placed further back from Woodman, so there’s space between her and her viewers, as if the viewer is watching from afar, afraid to approach the subject. The light from the window behind her is so blown out that it’s impossible to place the space in any specific location, urban or rural. Anyone observing this scene could imagine it in their own town.

Wearing only shoes and a necklace, Woodman is sitting nude on an old chair, and nothing here hides the emotional state she is in. Her face is forlorn and despondent, she looks very much lost and alone in her solitude. The shadowy silhouette of a figure on the floor feels ghostly, as if it were representative of something that used to exist, perhaps before the depression set in.

Finally, it is important to note that this reading simply comes from a reading of the photograph itself. Biographical evidence of Woodman’s life notes that she appeared to be happy during her time studying at the Rhode Island School of Design. Later, after graduating from her program, Woodman would develop depression as she struggled to get her work shown, and she did ultimately take her own life. There are some who have tried to argue that this work foreshadowed and illustrated her personal struggles with depression, but there are also those who argue that this was not the case. Olga Hubard cautioned people to be mindful of the impulse to psychoanalyze the artist, and that seems particularly important to remember when studying the work of Woodman. An artist can create imagery that explores ideas about anxiety, depression, and mental illness without the artist having to have also suffered from those maladies.

Jackie Dives. “Untitled.” Colour Film Photograph. ~1990s.

As a teenager, artist and documentary photographer Jackie Dives shot a lot of photographs on film but didn’t end up developing a lot of those rolls until after a few decades had passed. It took a lot of strength for her to develop the rolls as she knew they were taken during a period in her life when she lived with anxiety and depression. But she also considered them as representing a major gap in her artistic development, one that she was curious about. About her struggles, Dives says: “So much of my experience has been pretending not to be depressed, instead of figuring out how to live with it” (Berman).

Formally, this image is an untitled colour photographic self-portrait shot on film and the content it contains also informs the ideas about a teenager hiding her struggles with anxiety and depression. This untitled 1990s image was digitally scanned from its film’s negative for inclusion in the Georgia Straight article. It was also printed for display at a one night only, four-hour long exhibition held on March 30, 2017, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The size of the print is like the size of photo one would get from a one-hour photo lab, ~5”x7.

Overall, this photo has an off-white monochromatic colour palette that serves to informs its overall tone. It helps to secure the image in a kind of dreamlike state – a moment captured in time and held there for viewers to see. David Kastan and Stephen Farthing, speaking in their book ON COLOUR, described how monochromatic black and white, as well as sepia images, can exist simply as the colour of memories (201). Specifically, Kastan and Farthing explain how monochromatic greys can become a representation of, “Not of what we remember but the color of memory itself, which is always, at least in part, a kind of amnesia” (201). They further note how the greyness of black and white monochromatic photographs “…works to sequester their images securely in the past.” Here, Dives is wearing a simple, plain sweater that is either light tan, or even white in colour. The background of this photo is also very sparse, and contextually, this self-portrait of Dives is very minimalistic [an art movement that began in the 1960s as a rebellion against abstract expressionism and modernism. Minimalist art (whether it was in music, literature, or the visual arts), was characterized by extreme spareness and simplicity] in its feel than some of her other self-portraits. Ultimately, it’s safe to suggest that both the monochromatic tone and minimalist feel of this photograph lends to the emptiness one can feel when lost in the haze of despair.

Shot with a snapshot aesthetic, this photo also has a slight vignetting, which Adobe describes as: “…a darker border - sometimes as a blur or a shadow - at the periphery of photos. It can be an intentional effect to highlight certain aspects of the image or as a result of using the wrong settings, equipment or lens when taking a photo.” The vignette here enhances the overall ghostly feel to the image, and it removes it from being grounded in any one specific place and lends to the idea that the subject of the photo, whose facial expression conveys the emotion of someone barely surviving, exists in a kind of fog, both existentially and physically.

Unlike the work of Woodman, we can connect the ideas associated with anxiety and depression to the feelings Dives’s experienced as a teenager because Dives talks about this context in relation to the photographs she took during this time in her life. Dives has also discussed how she views photography as a kind of therapy and way of working through and exploring her experiences.

NOTE: This section on Dives primarily used work from a much larger piece I wrote in fall 2022 for a course at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, IDEA 2900, which can be found here.

Janelia Mould. “{ADORNMENT}.” Colour Photograph. 2018.

Janelia Mould is a fine art photographer who also explores the depression that impacted her life through her photographs. Like Woodman, Mould’s works are surreal and dreamlike, and often only show parts of her body. Speaking with My Modern Met, Mould notes: “I have purposefully left out the head and some limbs… I wanted to give a glimpse on how a person with depression might experience life, through creating a character that never feels fully complete” (Stewart).

Like Dives and Charkiewicz, Mould shoots her portraits in colour, but here her 2018 photo is grainy, and not tack sharp, mimicking the feel of an older roll of colour film, possibly shot in low light with a high ISO. It gives the portrait a hazy feel, as though the figure exists out of time, lost in the fog of despair. Here, it’s suggested that the unknown figure is also nude like Woodman, leaving the figure vulnerable to a viewer’s gaze.

On her belly is something that appears to be a tattoo, only here it’s an embroidery the figure is applying to herself in an almost nonchalant manner. There’s no blood, no suggestion that she is in pain as she threads the needle with red thread. This is telling as the pain associated with depression is also usually hidden below the surface of those who are suffering. It’s also interesting to see the figure do this to herself as some psychologists have linked the getting of tattoos to be representative of a person’s struggles with mental illness. One study conducted in July 2016 of 2,008 adults living in the United States found that “…people with tattoos were more likely to be diagnosed with mental health issues and to report sleep problems” (Wood). But by changing the tattoo to an embroidery, Mould is making a link to a tradition that is strongly feminine in its craft. It may also be leaning into the long held notion that more women suffer from depression than men, although there are psychologists who believe the difference lays in the possibility that women are more likely to report having depression than men.

Finally, Mould has called this piece “{ADORNMENT},” which refers to an embellishment or colourful decoration. A decorative distraction to keep people’s focus on something superficial. With each of Mould’s photos in this series, she quotes an author, in this case, Rachel Wolchin:

"I assure you, l'm not put together at all.

Nor am I broken.

I'm recovering -

finding the beautiful in the ugly and stitching it into my life."

The quote emphasizes a desire to overcome the depression, but it leaves one wondering if the approach is in any way sufficiently sustainable.

Eva Charkiewicz. “Everything Passes Away.” Colour Photograph. 2021.

Eva Charkiewicz is another fine art photographer who explores the depression she’s experienced through the self portraits she’s produced. Like Dives, Charkiewicz sees her creative process as being therapeutic, noting how: “I want to show you my world (my four walls) – my photographs. I became interested in photography after being diagnosed with clinical depression. Photography helped me and still helps me with my emotions” (The Perspective Point).

Her 2021 photo, Everything passes away… is deceptively simple in its construction, and similar to the Dives photo above in its monochromatic use of colour. There’s an overall bluish grey tonal haze punctuated by her muted orange-red sweater. The red is reminiscent of a kind of life blood that’s being drained from the figure. And the blue grey haze feels like a wash of colour that’s been painted onto the image, one that also has a slight grainy effect that is evocative of the grain found in Mould’s photograph.

There are two figures visible, and the bodies of both figures face forward but there heads are turned towards each other, looking away from the viewer. All of these elements succinctly captures the isolating feeling that depression can have, leaving people turning inward, unaware of the world around them. That the figure on the right is more opaque than the one on the left suggests something about the individual is being lost due to the depression. It’s not that dissimilar to the impression of a figure on the floor of Woodman’s image.

Part Three: Summary (100-200 words)

What interested you about the theme you chose?

Why did you select these artworks?

Which age group or grade level did you have in mind when selecting this theme?

How would you introduce this theme to your students? What question could you ask or what activity could you develop to give them an entry point into the theme?

Ultimately, I was interested in the theme of depression as I’ve personally suffered from major depressive disorder for most of my life. And for better or for worse, it’s a theme I’ve also explored in my own fine art photography and non-fiction writing.

Seeing how other artists examine this malady through their own work also interests me, irregardless of whether or not they have personally suffered (to this end, I am reminded how Olga Hubard cautioned people to be mindful of the impulse to psychoanalyze the artist and their process, which is why I started with an examination of work by Francesca Woodman).

In terms of an age range for presenting this work to, I believe the work could be shown and discussed with those who are aged 13 and older. The work shown here by Woodman and Dives was done while they were teenagers, and the issues of depression, anxiety, and loneliness impacts many teenagers. It’s also known that making art can serve as a kind of therapy for working through difficult feelings and struggles.

To that end, I’d introduce the theme of depression by having students share moments when they’ve felt sad or depressed, or moments when they’ve seen family or friends feel that way. We’d then discuss how art could provide a way for expressing those feelings. Finally, I’d have students create an artwork that expresses the emotions they’ve felt or seen others feel, as discussed earlier in the session. Students could use whatever medium of expression they felt drawn to: collage, drawing, painting, photography, or even writing a poem or short story - fiction or memoir.

Works Cited…

Berman, Sarah. “Faded Snapshots from Teen Years Spent Lost and Depressed.” Vice, 19 Feb 2017.

The Perspective Point. “Eight artworks inspired by mental health problems.” The Guardian, 17 Jan 2018.

Stewart, Jessica. “Interview: Photographer Explores Own Depression with Surreal Self-Portraits.” My Modern Met, 10 Mar 2017.

Tate. “ART TERM - SURREALISM.”

Wood, Janice. “People With Tattoos More Likely to Also Have Mental Health Issues.” PsychCentral, 27 Jan 2019.

Peer Reviewed Feedback