Seeing so many of the pieces that formed RISING at Yoko Ono’s show at the Vancouver Art Gallery cut deeply into my soul, leaving me choking back tears, and leading me to again ask why so many people are so utterly cruel. It was maybe the most difficult Artist’s Date I’ve had in a long time.

I say Artist’s Date as it has a very specific reference to a concept first developed and explored by Julia Cameron, in her book, The Artist’s Way, which, for me relates as a exists as a means of defining a creative inspiration adventure. And it’s how I’ve often approached going to an art gallery. Specifically, Cameron describes how:

“An artist date is a block of time, perhaps two hours weekly, especially set aside and committed to nurturing your creative consciousness, your inner artist. In its most primary form, the artist date is an excursion, a play date that you preplan and defend against all interlopers. You do not take anyone on this artist date but you and your inner artist…”

Stepping into the Feeling of a Voyeur

It felt oddly ironic, or maybe even irresponsible to have just sat a few moments earlier watching CUT PIECE (1964), blown up so big on the gallery wall, watching it play through several times. This was the first time I had watched CUT PIECE in either a non-classroom setting with other fine art students, or later, by myself on a display that wasn’t larger than say the thirty-two inches of my computer screen, or on the small screen of my iPhone. Ono too, is very familiar with the various kinds of displays and technologies that exist, as her video art was projected, displayed on televisions, and one even involved an older iPhone.

In CUT PIECE, one guy has always stood out for me in Ono’s participatory performance artwork. He was young, maybe in his late 20s or early 30s. I feel like he could be some kind of investment banker, maybe working on Wall Street. Like all of the men and women who came up onto the stage, he was stylish, wearing a nice, crisp white buttoned up dress shirt, and dark, pressed chinos or slacks (dress pants). He went back up onto the stage at least two times, and he was eventually bold enough to actually cut the clothing that salt closest to Ono’s naked skin. Close to her stomach. Close to her breasts, to the point where he even cut the straps of her slip, and then her bra. Ono caught the bra, holding it close to her body, so as not to completely let the clothing fall to reveal her breasts, and to possibly prevent him from claiming it as a prize. But she was so vulnerable in that moment. While he was so in control, smiling as he cut and talked to people we couldn’t see. The camera moved all around Ono, and you could also see still photographers snapping away, usually directly opposite to where the video cameraman was positioned. Recording it for posterity. There are some who argue that a performance piece like this loses its power when it’s watched as a recording. But to me this black and white recording is still powerful, almost sixty years later.

I kept thinking of how it felt wrong to be watching CUT PIECE, which was so intimate and vulnerable. with Ono as the centre of the piece. She didn’t really engage anyone who came to cut pieces off of her clothing with rather large scissors. She often looked away, rarely making eye contact. At times, Ono had tears welling up in her eyes. Having taken first aid and even sculpturing courses we were taught to always move scissors that were close to the body away from say the face or chin. So it was difficult watching people cut in directions I was taught to avoid. There were times when a part of me wanted to shout out to the various men and women on the big screen, “to cut in the opposite direction for fucks sake!” But you don’t shout it, you sit there, keeping an uncomfortable personal silence. Like a voyeur perhaps. Declarative statement: as a man, I shouldn’t have watched. One more: as a man, there was nothing I could do, as I was watching a moment in history that had been recorded to be displayed on the walls of art galleries.

Although I wasn’t restrained or forced to watch, the image of Malcom McDowel as Alex in director Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film, A CLOCKWORK ORANGE came to mind as I sat there. I wasn’t yet crying on the outside, but I can imagine some people’s reaction to this work overtime probably evoked the kind of terror that is highlighted by Kubrick’s vision – terrified, shocked, and with a tear streaming down his cheek. But upon watching CUT PIECE again for this write up, I noticed how the audience was at times even laughing as the performance continued. I’d like to think it was a kind of defensive laughter, but it didn’t really feel like that. At one point, when the man I mentioned above cut her bra straps, someone in the audience can be heard exclaiming, “stop him!” But no one did, and the performance continued.

Re-enacting & Reinterpreting Performance Based Artworks

I’ve seen CUT PIECE re-enacted by other female and even male artists. But they weren’t as powerful. In some videos, the settings, were too clean. The old hardwood flooring of the stage Ono sat on appeared very haggard and was far from pristine, it felt like you shouldn’t be there. And while I can admire male artists re-enacting difficult pieces, the few I’ve seen don’t pack any punch, and I think that’s because this piece is so rooted in critiquing patriarchal structures, such as the objectification of women, as well as exploring the concept of the male gaze (although that specific term wouldn’t come into existence until almost eight years after the first performance of CUT PIECE), which are issues males don’t really face on a day to day basis. Another large issue for me is the fact that Ono is of Asian descent, which evokes ideas about how Asian women can be fetishized, something that doesn’t exist for individuals of Caucasian descent who performed the piece (although when women perform this, it’s still more powerful than when men reenact it). One final critique of these re-enactments is that, from the ones I’ve found on YouTube, those who post clips of these reenactments often overlay some kind of soundtrack, and they also speed up the footage so it goes by more quickly. On the pieces that did this, I offered comment that they should consider not doing these thing, as part of the power of the original piece was watching it play out in real time, creating more tension in the mind of the viewer. This isn’t to say that Ono didn’t manipulate time, but instead of speeding up the footage, she would utilize jump cuts to edit out more mundane things like people walking onto and off of the stage.

In spending time with CUT PIECE, I also reflected on the parallels between it and Marina Abramovic’s RHYTHM 0, performed a decade later in 1974. Abramovic’ s work used 72 objects that could be used on Abramovic in any way as a participant desired. According to the Tate website, the objects included:

“gun, bullet, blue paint, comb, bell, whip, lipstick, pocket knife, fork, perfume, spoon, cotton, flowers, matches, rose, candle, mirror, drinking glass, polaroid camera, feather, chains, nails, needle, safety pin, hairpin, brush, bandage, red paint, white paint, scissors, pen, book, sheet of white paper, kitchen knife, hammer, saw, piece of wood, ax, stick, bone of lamb, newspaper, bread, wine, honey, salt, sugar, soap, cake, metal spear, box of razor blades, dish, flute, Band Aid, alcohol, medal, coat, shoes, chair, leather strings, yarn, wire, sulphur, grapes, olive oil, water, hat, metal pipe, rosemary branch, scarf, handkerchief, scalpel, apple”

The Tate website’s description of the piece also noted how:

“…for a period of six hours, visitors were invited to use any of the objects on the table on the artist, who subjected herself to their treatment. The artist has stated, ‘the experience I drew from this work was that in your own performances you can go very far, but if you leave decisions to the public, you can be killed’ (quoted in Ward 2009, p.132).”

So, the similarities between the two pieces appears to be clear, but Abramovic expanded upon Ono’s work in terms of the duration and length of the performance, as well as in regards to the much wider variety of tools made available for audience members to use. Art Critic Frazer Ward, in his book NO INNOCENT BYSTANDERS: PERFROMANCE ART AND AUDIENCE, was present for the performance, described how:

“It began tamely. Someone turned her around. Someone thrust her arms into the air. Someone touched her somewhat intimately. The Neapolitan night began to heat up. In the third hour all her clothes were cut from her with razor blades. In the fourth hour the same blades began to explore her skin. Her throat was slashed so someone could suck her blood. Various minor sexual assaults were carried out on her body. She was so committed to the piece that she would not have resisted rape or murder. Faced with her abdication of will, with its implied collapse of human psychology, a protective group began to define itself in the audience. When a loaded gun was thrust to Marina's head and her own finger was being worked around the trigger, a fight broke out between the audience factions."

Interacting With & Reflecting on Performance & Video Based Artworks

I can’t say this surprised me, but in looking up the short film FLY online, it’s Internet Movie Database rating is only 4.4 / 10. By contrast, CUT PIECE has 6.5 / 10 on the same website. I wasn’t surprised by these ratings because these two works aren’t traditional films, they are avant-garde pieces of video art. The camera lenses in each of these films cover difficult and untraditional subjects, and the resulting images that are in no way easy to consume. There is also no overall traditional narrative to any of these video works, but there are many metaphors that can be found buried within the images that make up these pieces.

People watched CUT PIECE for a much longer time than they did FLY. FLY was more than double the length of CUT PIECE, running at approximately 25 minutes to CUT PIECE’S 9 minutes. More people spent time watching CUT PIECE. They sat with it and watched it for longer periods of time than they did other works. I found it interesting how people would watch FLY for a bit and then read the description on the wall before walking away. Only one other piece was longer, BOTTOMS (1966), which ran at approximately 80 minutes. I didn’t watch this one for its entire length, only a few seconds really, as I was cognizant that I wouldn’t have had enough time to wander through the entire show if I did watch all of it, as the gallery was closing at 8pm that night, and I had arrived around 6:30pm. In an activity posted online for kids visiting the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, it’s noted how: “Researchers in museums have found that 30 seconds is the average amount of time visitors spend in front of works of art.” And from my anecdotal evidence, of a few short videos I shot of people interacting with FLY, this definitely seems to be the case. But it also seemed dependent on what part of the film a viewer saw when they approached. If it was a more abstracted view of the body, or a part of the body such as a closeup of the face, people stayed with it. They moved away from it if it showed a breast, and especially when it showed a vulva.

Thinking About Flies

Specifically, FLY opens with a fly crawling across a white surface, and then up alongside the leg of the woman, before eventually flying up a bit to land on the leg, the camera up so close that at first one wasn’t sure what they were seeing. Was it a leg? A foot? Toes? Ono’s camera moved from tight shots of the body to wider shots. At times, parts of the body were very abstracted, and held a quiet beauty. Some shots were like watching the landscape of a desert, with all of its desolation expanding out towards a far off horizon line. At other times, one was very aware of what Ono’s camera was looking at. Be that a shot taken with the camera on the bed, between the woman’s legs, looking directly at a single housefly crawling over her vulva, and even disappearing briefly between the woman’s labia majora before coming back out again. It was definitely uncomfortable to watch, even as an artist who has consumed imagery like this before. I say Ono’s camera, but I’m forgetting that the film is also directed by her husband, John Lennon, so it’s difficult to say who directed the placement of every single shot, although I assume there was a lot of agreed upon decisions made by this husband and wife team in the making of their film.

At first, I thought the subject on the bed was Ono herself, as she was the prominent figure in CUT PIECE and FREEDOM. But the credits for the short film revealed that the figure was Virginia Lust. With a name like that I actually thought she might have been a porn actress. There’s little to no information about her that comes up on a simple Google search. IMDb lists her as an actress, and there is a single entry for a gallery director who ran her own gallery in New York City during the same time that Ono was working in the city as an artist. So it’s entirely possible that the gallery director and publicist was the same person who appeared in Ono and Lennon’s film. Knowing who the figure is definitely changes the meaning of the piece for me, especially as a male viewer. Or maybe not… ultimately, it’s still a woman, a solitary and nameless figure as you don’t learn her name until the film’s end credits. It could be any woman at the end of the day, and the way she didn’t move, the way she just laid on her back, it was like she had been tossed aside, perhaps a sex doll of sorts, not being used, not even waiting to be used again, just lying there. Just another object for flies to land on. Eventually, Ono’s camera moves up away from the body it spends the majority of the piece focussed on, to move towards a nearby window, to the blue cast sky of the lonely rooftop that sat across from the window.

Reflections on Sound

There was sound to FLY, but given the film was being played on a small television, it was difficult to hear the work. When one worked to listen, they heard almost cartoonish and comical sounds of a person imitating the sounds flies made. But one particular piece, PAINTING TO HAMMER A NAIL, originally shown in 1966, made it very difficult to listen to the surrounding video pieces. NAIL invited viewers to to literally pound nails into a large wooden, white gessoed panel. The hammering of nails by so many guests was almost nonstop, and it formed a part of the gallery’s soundscape as soon as one entered the exhibition space. It was definitely unsettling and off putting. And at first, I didn’t know where this noise was coming from, or how it was produced. As I watched CUT PIECE, my mind did wonder where the noise was coming from and I actually assumed it was the soundtrack of another ONO video playing in the next area of the gallery. I definitely did not think that it was from actual gallery goers interacting with another artwork.

But it’s so important to note how the sound of nails being hammered absolutely dominated the soundscape of the gallery, making it difficult to fully experience pieces like FLY. The sound of nails being pounded into the wooden canvas was loud and sharp, moving across the higher end of the decibel scale. The sound of the atmosphere created by the sound of the hammer hitting nails reminded me of the climatic scene of the 1997 Paul Thomas Anderson film, BOOGIE NIGHTS, where the central characters visit the house of a drug dealer, where an unnamed Asian fellow was setting off small firecrackers. That action really heightened the tension in the scene, in a way that I’ll never forget. And for me, the nails being hammered into the wooden panel exists at a similar level of providing discomfort – it kept me on my toes as I moved through that area of the gallery, it didn’t let me settle into watching or interacting with any of the pieces in that immediate area. Oddly enough, the only time when I felt present in that immediate area, was when I was hammering the nails myself. I channeled the 1986 film THE KARATE KID 2, where Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) teaches his student Daniel (Ralph Macchio) about finding balance and presence through breathing, which allowed him to strike a nail and pound it into a two by four with a single blow. I’m proud to say I was able to strike three nails in the Ono piece in this exact manner.

Lightening things up

Of course, not all of the works in this immediate area were as dour as FLY or CUT PIECE. Many works were much more lighthearted. INSTRUCTIONS FOR LIFE which Ono started in 1955 again provided a more immediate chance for interaction between viewers and the artworks in the gallery setting. Specifically, the Vancouver Art Gallery described the works that it displayed as THE INSTRUCTIONS FOR YOKO ONO, as follows:

“…a new kind of relationship with the viewer through an invitation to play an active part in the completion of the artwork. None of the works came to the gallery in crates with the status of original, unique art objects in the traditional sense. Instead, Ono conceived of these works to be produced by the exhibitor with agency given to the viewer to complete the work – a fleeting physical and mental communication that upends the traditional commercial system.”

These small pieces helped provide a break from the more serious works in the area. But they weren’t meaningless, each provided a means of reflecting on the present moment, and one’s place in life. Here are a few of them, which were printed directly onto the gallery walls:

Art as a Means of Exploring Serious Issues

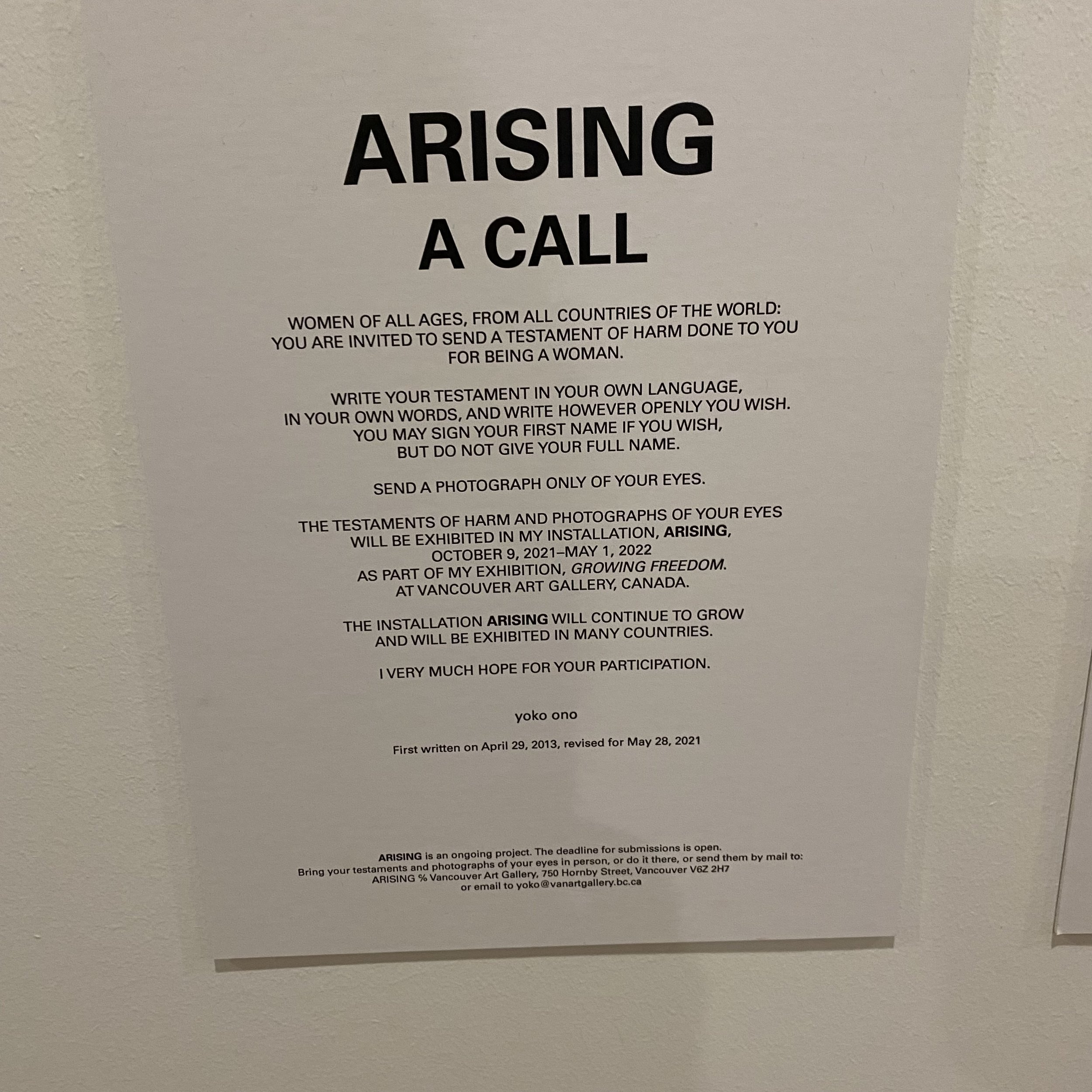

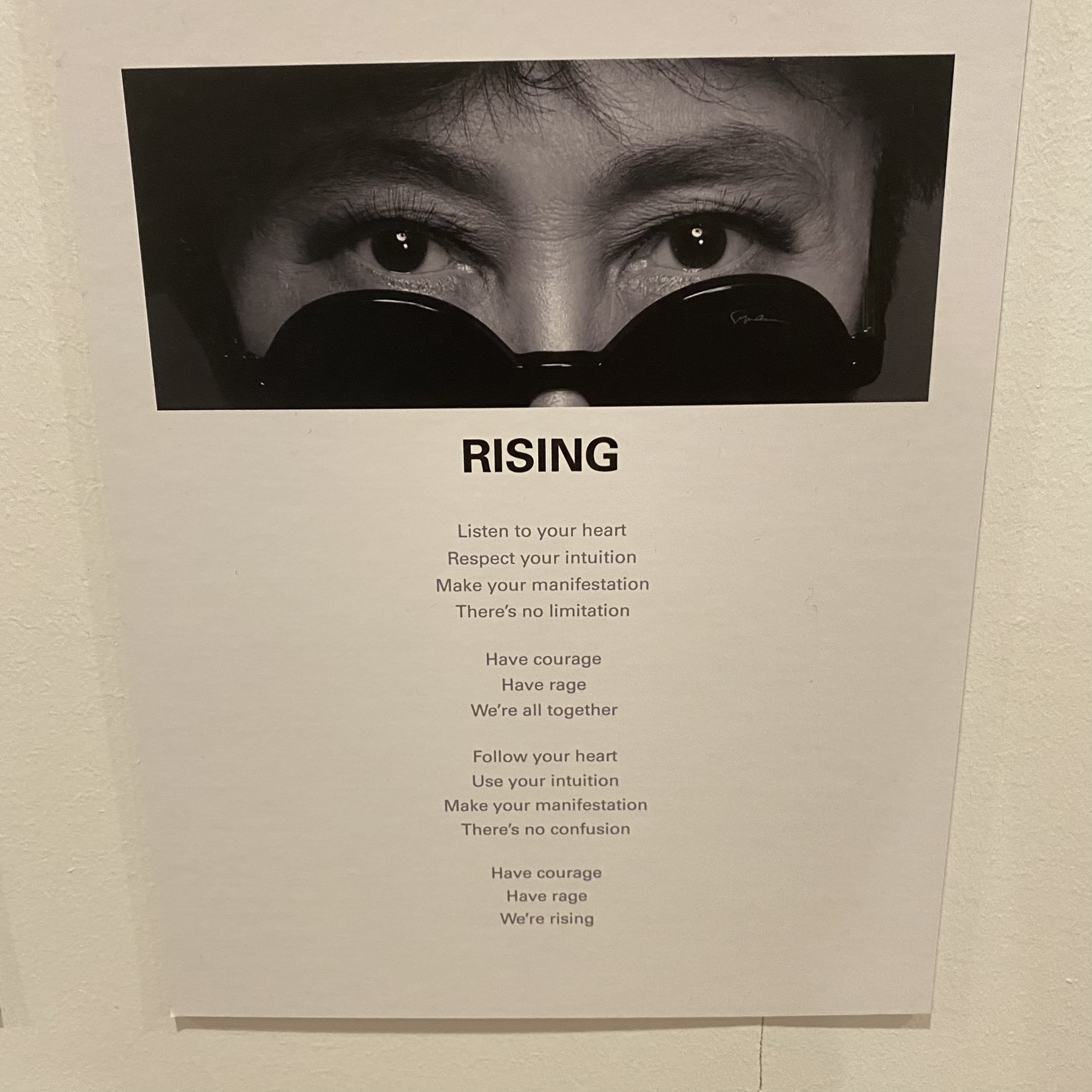

RISING touched on the stories of survivors of assault. Sexual assault primarily. Rape. Formerly, RISING was composed of row after row of testimonials printed onto single blank letter sized page. Above each block of text appeared below a closeup snapshot of a single pair of eyes. These photos and testimonials were all anonymously submitted in response to an ongoing call Ono has put out for this project.

I originally wrote on Instagram how some of the eyes were definitely the eyes of survivors, where I felt a great strength in some of the eyes. I also noted how other eyes felt as though they were still broken with grief – lost in the memories of what they had endured. But I’m not sure I expressed myself correctly: this is not to say that those who were still suffering were weak. Vulnerable, yes, but at a different stage of grieving and dealing with the abuse they had endured. But all of them were strong, for the very act of sharing their stories, which is the bravest thing anyone can do. The stories weren’t easy to read. For some, it was a single act of abuse. For others, generational abuses… and maybe I’m using the wrong word phrase but one story discussed abuse received from her grandfather. And from her father. And her boyfriend.

Ono’s works are important for the fact that they all explore important issues that women face everyday. What made interacting with this show difficult for me was the fact that issues Ono dealt with in works that are now around fifty years old are all still prevalent today. Moving through RISING was a bit more difficult for me because I immediately recognized the eyes of one of the stories that were shared. The chances of this happening shouldn’t be shocking, as the statistics are sadly very clear – in the United States alone, 1 out of 6 women has been the victim of an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime (and this number is 1 out of 33 for men). And these numbers are likely very conservative, as over sixty percent of sexual assaults go unreported to the police. I nervously reached out to her a few days after seeing the show, to confirm that it was her, and it was. I also did the bare minimum I knew to do, I apologized to her for having to experience what she did. And this is why I was so moved to tears, because one of these very personal stories hit closer to home simply because I knew the survivor.

Concluding thoughts

Between the works placed at the start of the show, and the ones near the end, were works created by Ono in collaboration with John Lennon, which I just couldn’t look at for very long. I found these difficult to look at, especially one which was a framed piece, that contained the simple words, I LOVE JOHN. Across from it was another similar piece, which simply said, I LOVE YOKO. I thought I had a beloved once, who I told I LOVE YOU so often, but I guess I never showed it as well as I could have. We too made some amazing art pieces together. But she left me long ago, and now I don’t think she ever makes art anymore, and that breaks my heart. I take the blame for us not working.

I’m so sorry.

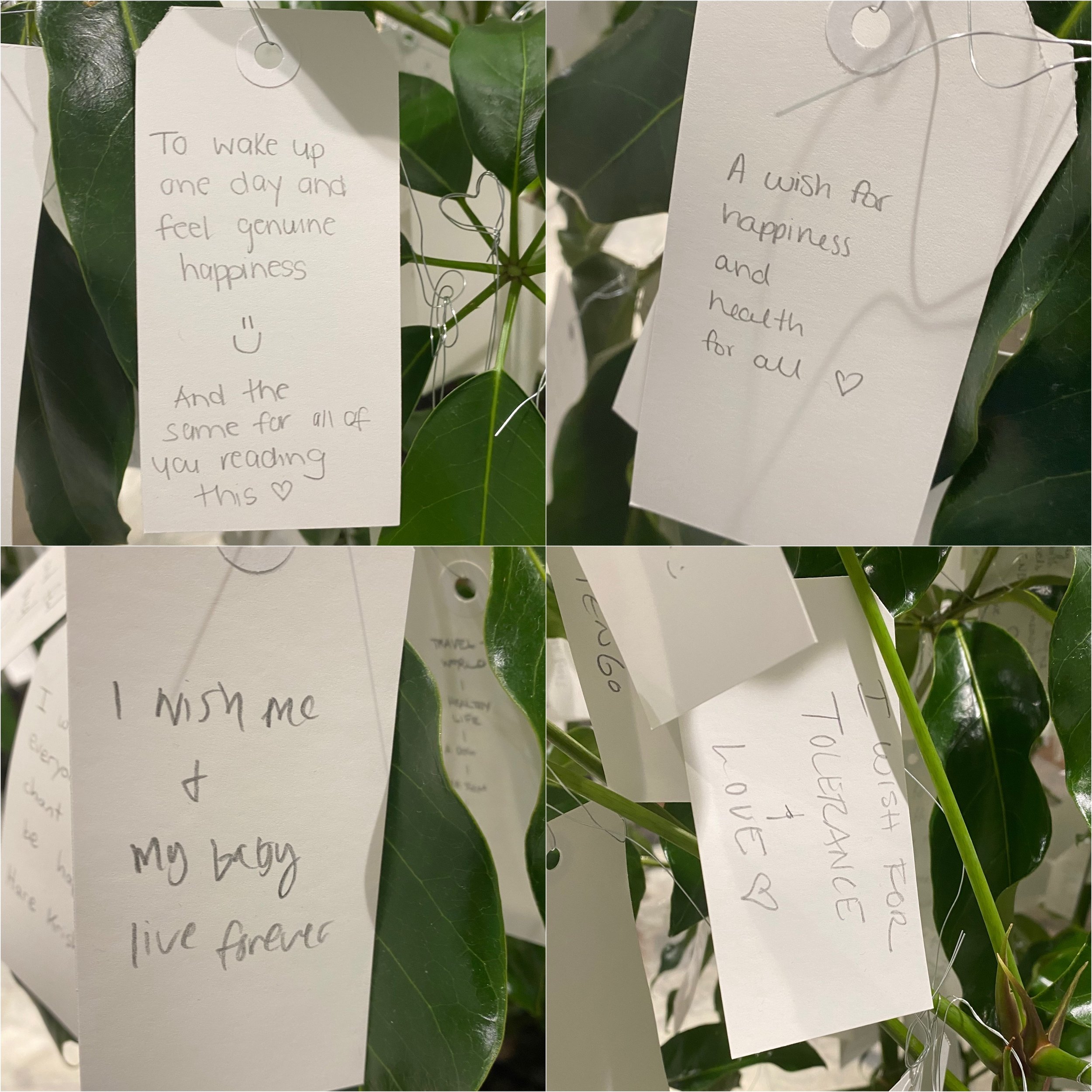

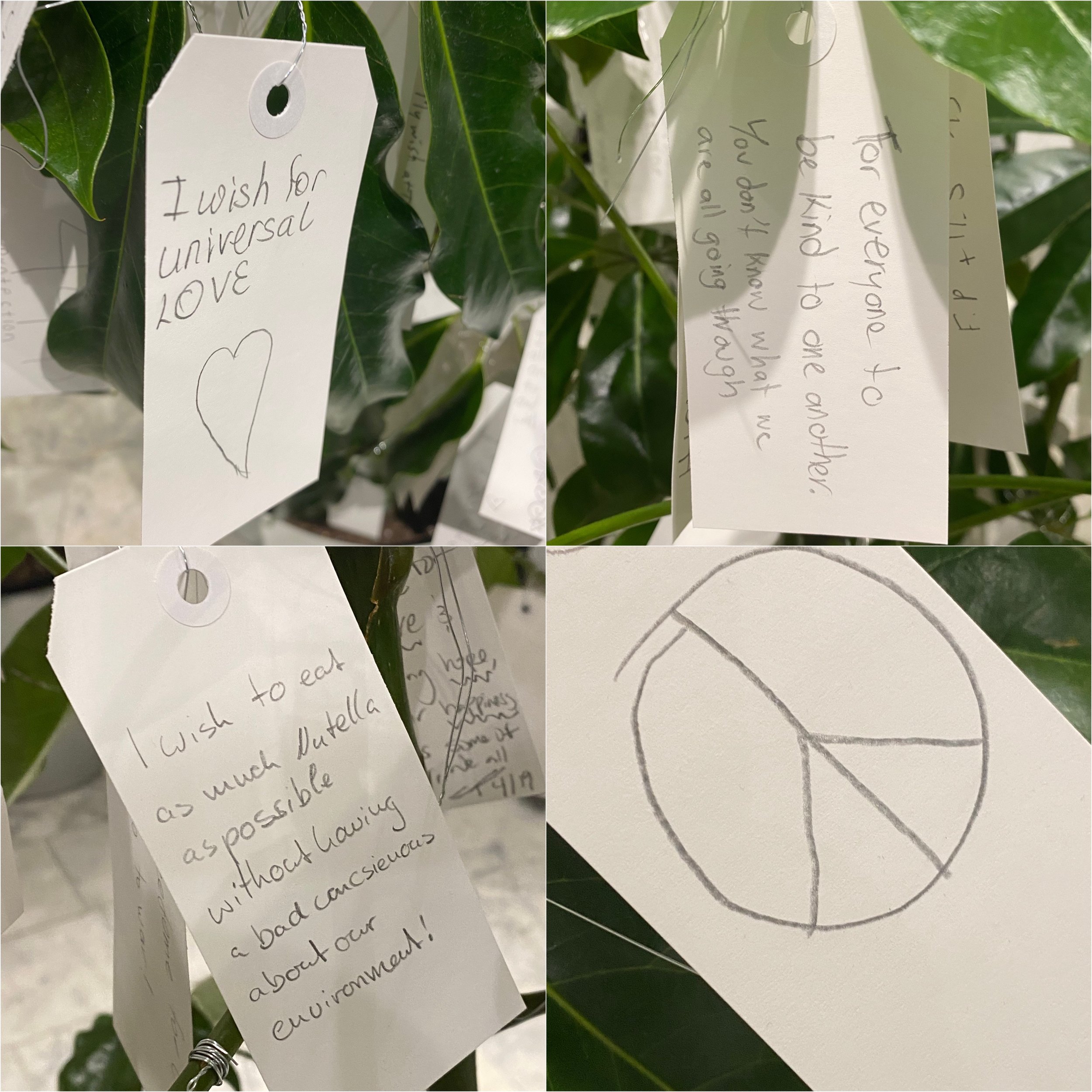

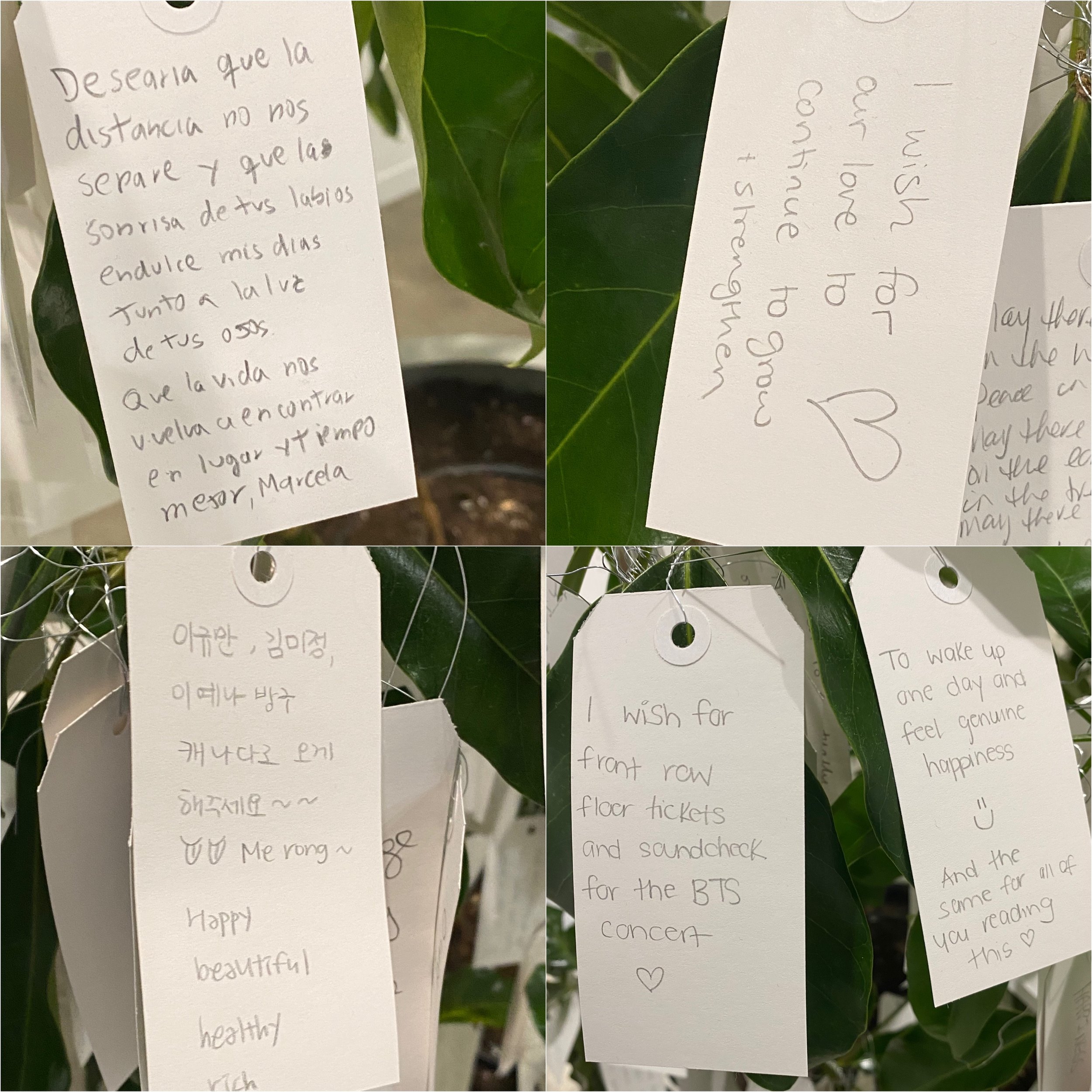

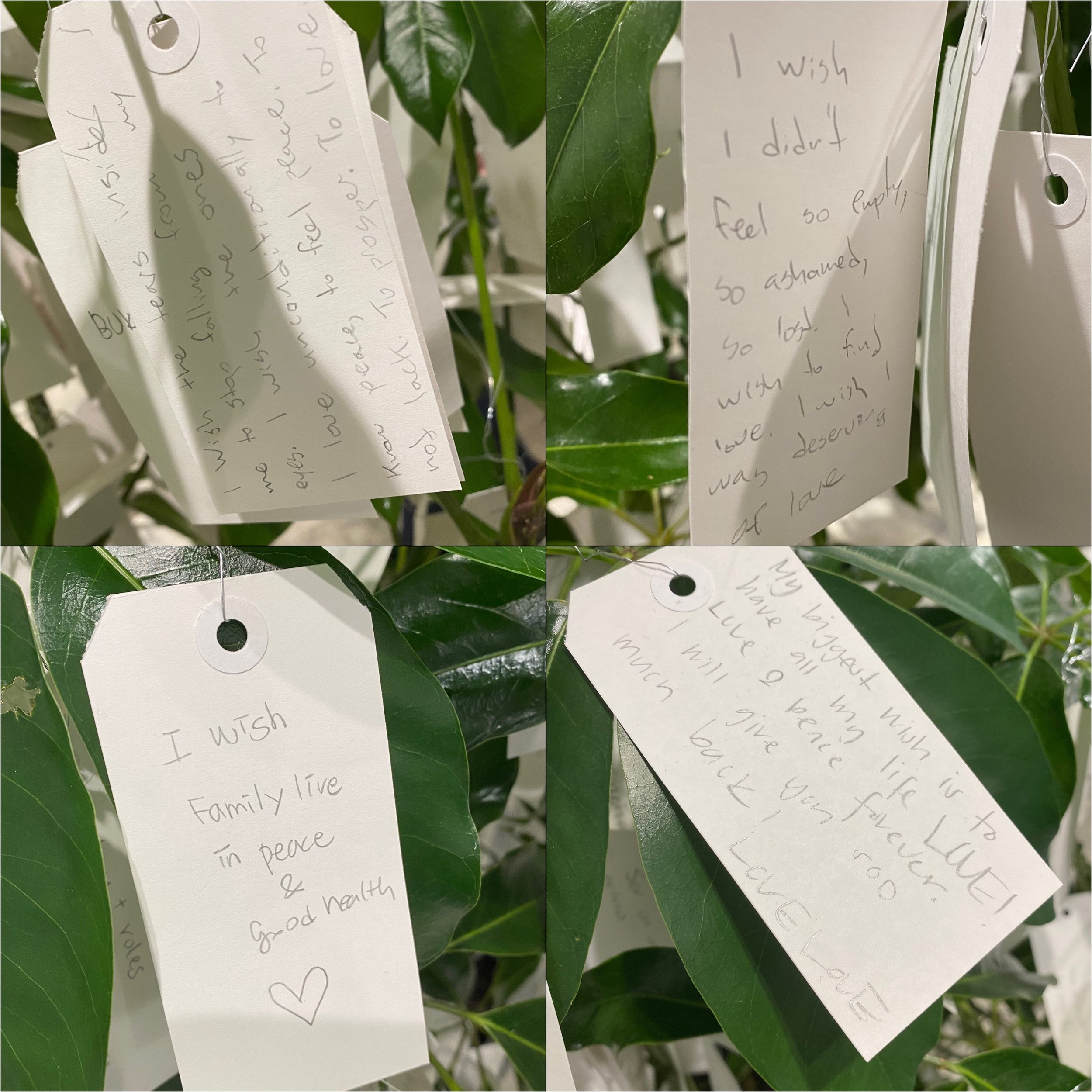

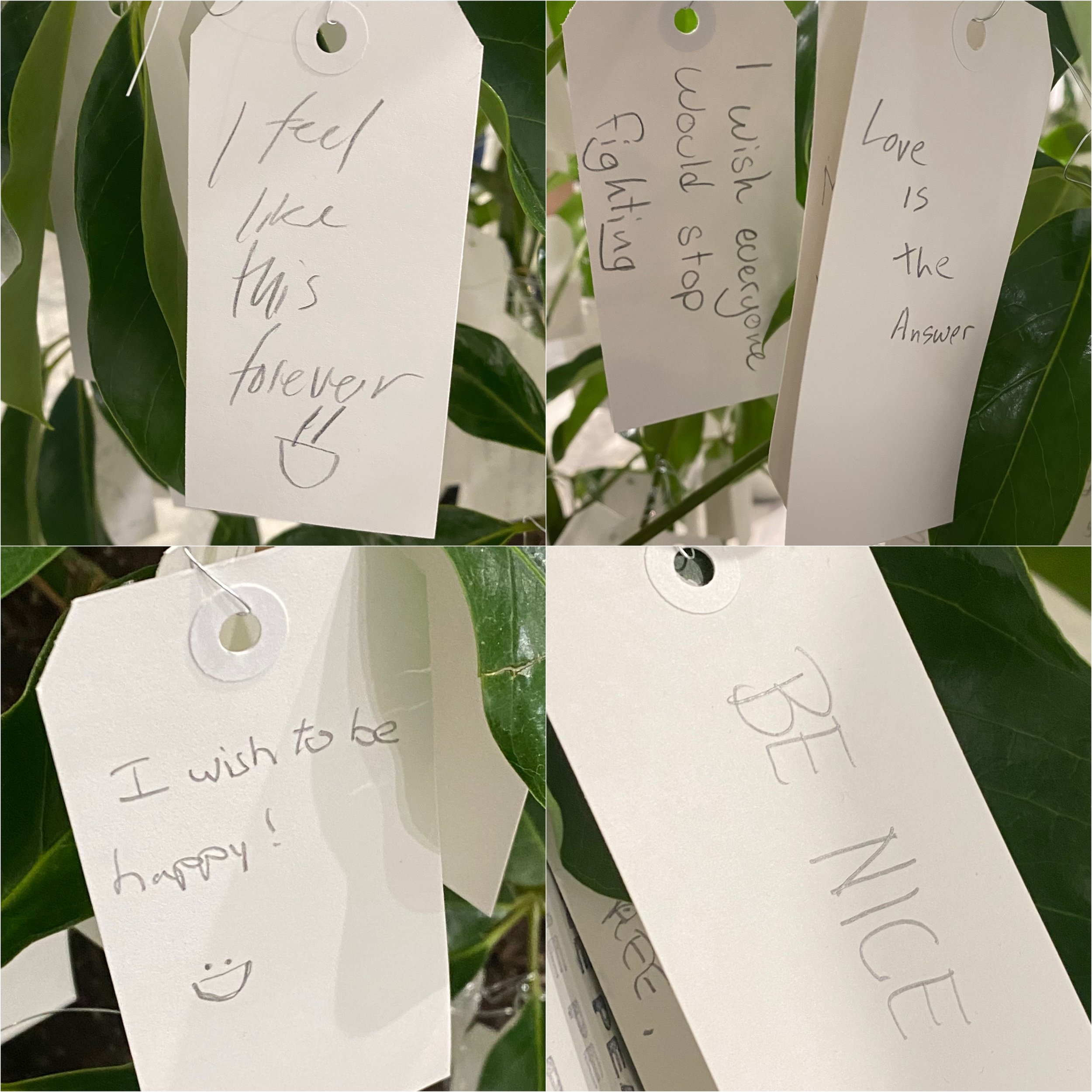

As I left the small area that was dedicated to RISING, i entered into an area that held works which appeared to be collaborations with local First Nations. I held my head down, as the tears were streaming down my face. The sobbing and choking back tears was difficult as I moved through WISH TREE (1996 / 2021), another interactive piece which encouraged visitors to record a wish and place it on any one of several trees that were in the area.

I wish I hadn’t waited until the last week to see this important show. My depression has made it difficult to get out to shows, and this was, in fact, the first art show I’ve attended since February 2020. It’s an experience I don’t think i’ll ever forget. It was a uniquely solitary experience, and deeply moving. If I could, I’d go back with an entire day free to really live with every piece in the exhibition.

This post originally started life as one of my subverted selfie project posts on Instagram.

Instructor Feedback

“Your submissions were wide-ranging, creative, honest, expressive as well as carried many rich insights, personal and societal, emotional and spiritual. There was enough there to also count toward Assignment#3 and the individual presentation. These are thus considered complete. Thus, the only component missing is the final applied research paper/portfolio worth 18 marks. You received a high A/cusp of A+ overall for 82% of the course, which makes your current grade in IDEA 3302 a B.” - Dr. Rajdeep Gill, April 25, 2022