06 - Classical Narrative Structure

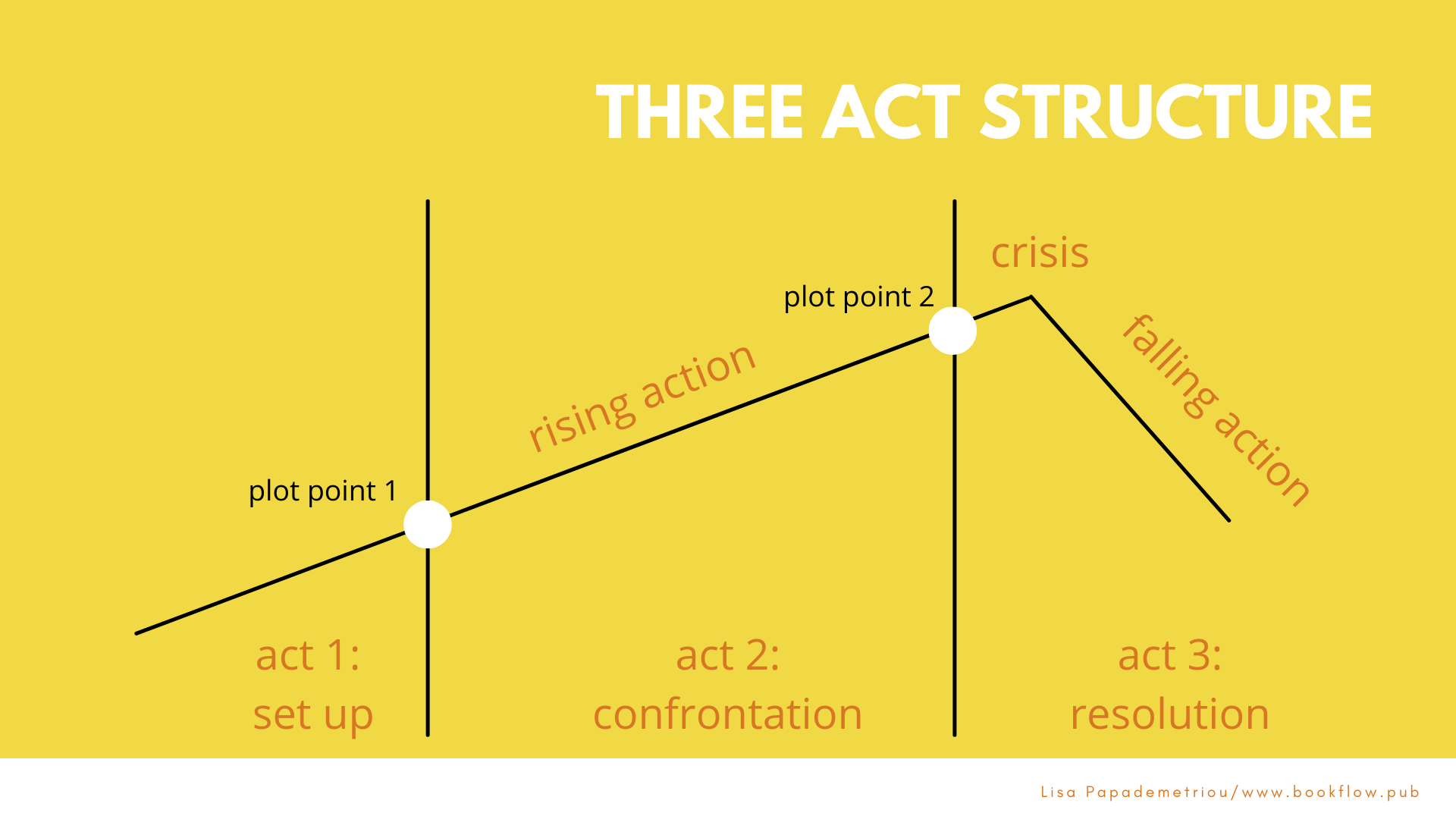

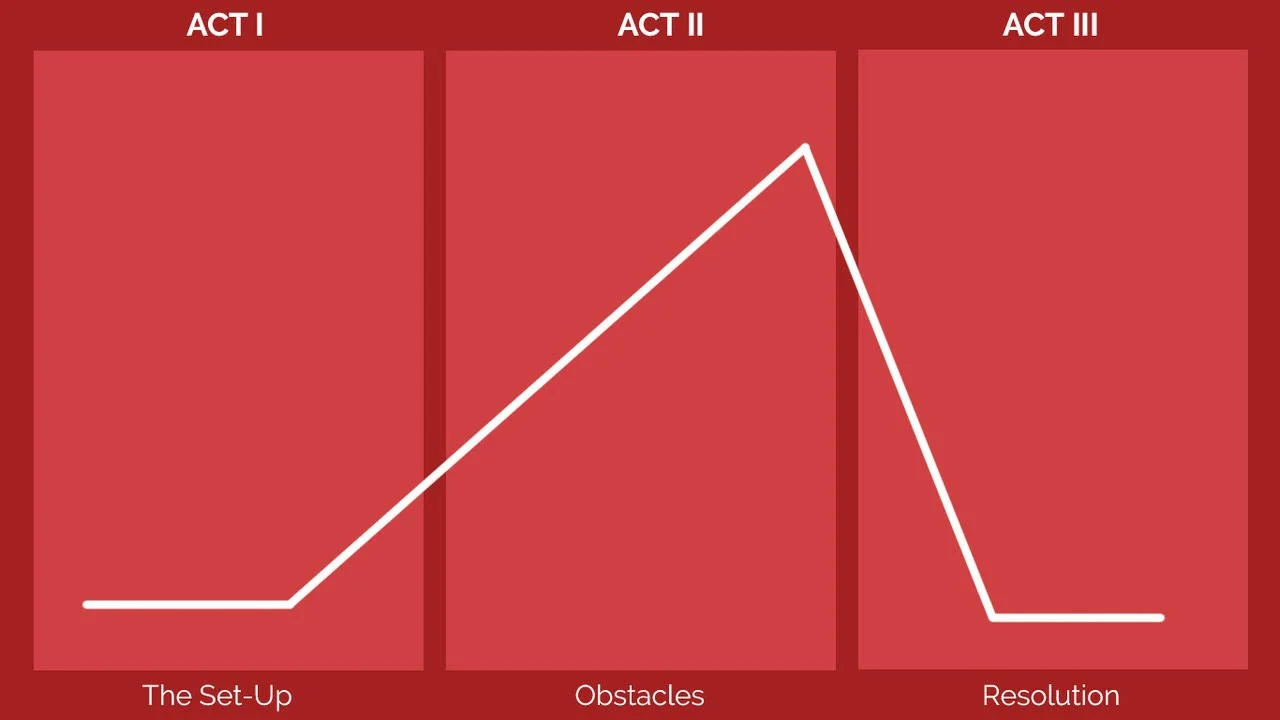

Many movies have a three act format to organize the story:

ACT I - The Setup

ACT II - The Development

ACT III - The Resolution

ACT I - THE SETUP

Introduces:

the main character in the story and their goal;

the main conflict; and

the major antagonist.

It “hooks” and captures an audience’s attention.

ACT I is typically the first 25-30 minutes of the movie.

PLOT POINT > Act one typically ends with what’s called a plot point > a major twist or surprising event that propels the story forward into another act. It provokes the beginning of another act. Specifically, it is a significant event in a story that changes the direction or outcome of the narrative often impacting the characters and the overall story arc. It’s a major turning point that pushes the story forward and keeps viewers engaged. For example, in…

Some Like It Hot (1950), the plot point in act one is when the main characters played Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis, witness a mob hit and barely escape being killed themselves;

The Planet of Apes (1968), the plot point that ends act one is when the astronauts discover that the planet they have landed on is run by apes; and

Rocky (1976), the plot point that ends act one is when that Apollo Creed has decided to give Rocky a shot at the Heavyweight Championship title.

ACT II - THE DEVELOPMENT

Introduces:

Plot complications and obstacles are added to the story;

Cause-Effect moments propel things forward for the main character(s);

The action points toward a necessary climax; and

ACT II is typically 50-60 minutes in length.

PLOT POINT > A plot point also ends the second act… for example, in…

Some Like It Hot (1950), act II ends is when the mobsters find the Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis characters;

The Planet of the Apes (1968), act II ends when our main character escapes his captivity; and

Rocky (1976), act II ends when Rocky comes home and tells Adrien, who is sleeping, that he can’t beat Apollo Creed. However, he tells Adrien he just wants one thing, and that’;s to go the distance with Creed to prove to himself that he’s not just some bum.

ACT III - THE RESOLUTION

Deals with:

The Climax, where the story’s main conflict comes to a dramatic confrontation, and where key struggles are waged and an eventual victor is determined (especially in Hollywood films), which is usually the hero; and

Closure is introduced into the story, which means that all the major conflicts, issues, or ideas in the story are resolved. The so-called “Hollywood ending” is the most popular kind of closure in a classical narrative.

ARTIFACT 02 > Papademetriou, Lisa. “Three Act Structure Graph.”

ARTIFACT 01 > Nelson, Kevin. “The Three Act Structure.”

MORE ON PLOT POINTS

MAJOR TURNING POINTS: Plot points are not just any event, but major events that shift the story’s momentum and influences what happens next.

CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT: Plot points often serve as catalysts for character development, forcing characters to make choices and face challenges that change them.

FORWARD MOMENTUM: Plot points ensure the story moves forward, creating a sense of anticipation and keeping viewers / readers invested.

DIFFERENT TYPES: Plot points can be used to surprise viewers / readers, introduce new challenges, or offer a fresh perspective on the story.

A PLOT POINT is any incident, episode or event that ‘hooks’ into the action and spins it around into another direction. They are a major story progression and keep the storyline anchored in place… but they do not have to be big dynamic scenes or sequences. They can be quiet scenes in which decisions are made. It can even be a moment of silence. Ultimately, the purpose of a plot point is to move the story forward, toward the resolution.

07 - Suspense vs Surprise

What’s the difference between SUSPENSE and SURPRISE?

Wikipedia notes how: “Suspense is a state of anxiety or excitement caused by mysteriousness, uncertainty, doubt, or undecidedness. In a narrative work, suspense is the audience's excited anticipation about the plot or conflict (which may be heightened by a violent moment, stressful scene, puzzle, mystery, etc.), particularly as it affects a character for whom the audience feels sympathy. However, suspense is not exclusive to narratives.”

Wikipedia describes how a surprise is an emotion representative of “…a rapid, fleeting, mental and physiological state. It is related to the startle response experienced by animals and humans as the result of an unexpected event… Surprise is intimately connected to the idea of acting in accordance with a set of rules. When the rules of reality generating events of daily life separate from the rule-of-thumb expectations, surprise is the outcome. Surprise represents the difference between expectations and reality, the gap between our assumptions and expectations about worldly events and the way that those events actually turn out.”

The course notes how in Edwin Porter’s THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY (19 ), a crowd is shown and the audience is surprised when a passenger from the crowd tries to escape and is shot to death. Porter however, could have built suspense into the scene by showing a closeup of the passenger, looking in different directions, causing the audience to wonder why this person was shown, and what they might be up to. Would they try to disarm the robbers? Join them? Or run? Doing this creates expectations in the audience by keeping them in suspense.

Related to the idea of a surprise, is the plot twist. Wikipedia explains how: “A plot twist is a literary technique that introduces a radical change in the direction or expected outcome of the plot in a work of fiction. When it happens near the end of a story, it is known as a twist ending or surprise ending. It may change the audience's perception of the preceding events, or introduce a new conflict that places it in a different context. A plot twist may be foreshadowed, to prepare the audience to accept it, but it usually comes with some element of surprise. There are various methods used to execute a plot twist, such as withholding information from the audience, or misleading them with ambiguous or false information. Not every plot has a twist, but some have multiple lesser ones, and some are defined by a single major twist. Since the effectiveness of a plot twist usually relies on the audience's not having expected it, revealing a plot twist to readers or viewers in advance is commonly regarded as a spoiler. Even revealing the fact that a work contains plot twists – especially at the ending – can also be controversial, as it changes the audience's expectations. However, at least one study suggests that this does not affect the enjoyment of a work.”

SECTION 03 DISCUSSION QUESTION

A typical movie goer will make a decision about whether he/she will like the movie around the ten minute mark of the movie. To put it another way, the story has to capture attention and interest ASAP. Name and explain a movie that you’ve seen where this was certainly true for you.

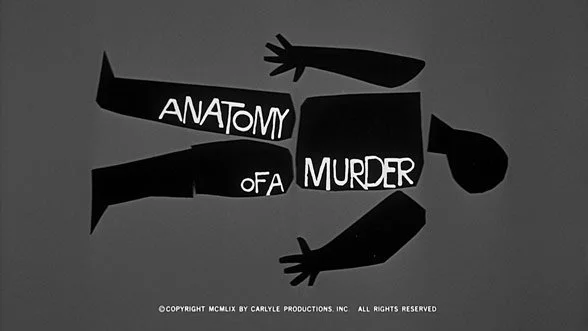

I find I’ve approached movies with an intention to want each movie going experience to be the best one it can be. I try to go in with no expectations, regardless of what I know about the film beforehand. But there have certainly been films where I have felt I will like a movie from watching its opening frames. For example, I recently watched director Otto Preminger’s 1959 feature film Anatomy of a Murder, a crime thriller starring James Stewart. First and foremost, the film’s title itself was intriguing to me. Specifically, the Oxford Dictionary defines ‘anatomy’ as being: “…the branch of science concerned with the bodily structure of humans, animals, and other living organisms, especially as revealed by dissection and the separation of parts.” But here, the anatomy is tied to the anatomy of a murder: specifically the structure and components of the dastardly deed as discovered through what the audience assumes will be a judicious and meticulously conducted investigation.

A frenetically energetic jazz score by American jazz pianist and composer Duke Ellington opens with the moans of an horn, and continues over the opening credits sequence and into the first moments of the film itself. I particularly loved the opening credits animation by graphic designer Saul Bass, which feature black cutouts of body parts superimposed over a fixed grey background. The first appearance of these parts gives the audience a full look at this abstracted body, with the film’s title laid over the body in a raw, printed capitalized white coloured font, as seen in Artifact 01 below. The text has the feel as if it could be text printed by an officer onto a police crime scene report, recording the telling details of the grizzly event transpired.

ARTIFACT 01 > Bass, Saul. “Opening credits title from Anatomy of a Murder.” 1959.

On one level, the overall image evokes that of a chalk outline one would find at a crime scene marking where a dead body had been found. But on another level, there is weight to the graphical pieces which serve to imitate the formation a whole, but one that has also been dismembered into individual parts (legs, torso, arms, and head). As the opening sequence continues, different parts of the body are focussed on individually, popping onto and off of the screen, or sliding in and out of view as the names of those involved in the production are either laid on top of, or beside the various appendages. The parts move at a quick but steady pace with the improvisational feel of Ellington’s score. Near the end of the sequence, an arm and the head appear on screen, and are each sliced into three parts as if they were being subjected to dissection through an autopsy. Apparently Preminger opened many of his films in a similar manner, as did other contemporary directors of his time including Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick where the animation and the music were woven together to provide a glimpse into the overall theme of the story being presented. Finally, “PRODUCED AND DIRECTED BY OTTO PREMINGER” appears in the same font over a completely black background.

ARTIFACT 02 > MovieTitles. “Saul Bass: Anatomy of a Murder (1959) title sequence.” YouTube, 28 Sep 2017.

Preminger shot Anatomy of a Murder in black and white, a choice purportedly made to keep production costs down, but, like so many film noir features before it, I found that this choice was one which helped to reinforce the film’s moral ambiguity. A car driven by star Jimmy Stewart’s character moves towards the screen, and passes the camera as the camera pans to follow the car’s movement. I liked how Preminger’s camera followed the movement, allowing the action of the car to come close to it and give us a closer glance at Stewart. The car’s headlights are bright in the relative darkness of the evening, the sky bright in the distance as the sun sets - it’s dusk. I appreciated how Otto Preminger used visual cues to present information about his characters and their setting to us, eliminating the need for expository dialogue. In essence, Preminger is following the ‘show, don’t tell’ guideline of storytelling by showing his audience information, allowing a viewer’s eyes to move over the screen during each shot to pick up information as they watch, as opposed to telling them that information through expositional dialogue. For example, the car passes by a city limits road sign that identifies Stewart’s destination as being “IRON CITY.”

As the car moves away from the camera, there is a dissolve from this brief scene on the outskirts of town to a city street lined with businesses but devoid of people and other cars. Stewart passes a lone individual, named Toybull, who is standing outside a shop door and they exchange a familiar hello. Stewart continues driving and the camera shifts its focus from Stewart to the lone man who turns and enters the building he’s in front of. The camera cuts to the inside of the shop, it’s a pub, and Toybull walks behind the bar and his dialogue with Mr. McCarthy (Arthur McConnell), an older man sitting at the bar, provides information that Mr. McCarthy knows the Stewart character. “Hey, your pal just drove into town, Mr. McCarthy” Toybull says. McCarthy comes across as a kindly older gentleman, fairly well dressed, but someone who enjoys his liquor. He tells Toybull that he will have to pay his bar tab tomorrow, which Toybull is agreeable to. Toybull trusts McCarthy. So, after putting back another shot, McCarthy bids Toybull goodnight and leaves the bar.

The scene then cuts back to another street, and Stewart’s character is seen driving to park in front of a darkened house. Another cut from beneath an overhang on the house, and another sign is visible which reads: “PAUL BIEGLER ATTORNEY AT LAW” with another sign below it reading “ENTRANCE.” He’s dressed rather informally, wearing a hat, jacket, a plaid shirt, and slacks. He’s also carrying a backpack, a satchel briefcase, and two long, slender tubes. He unlocks a door and the scene again cuts to have the camera inside the house, watching Stewart’s character entering the premises. Preminger’s carefully constructed mis-en-scene is on full display in Stewart’s home. Antlers hang mounted on the wall near the door and a note is stuck on one of the lower frontal tines. He takes time to read it before entering a mudroom where he places the tubes in a corner, and takes a fishing jacket out of the backpack to hang on a hook. To the right of the screen is a wooden pendulum wall clock, methodically counting the seconds of time that pass by us all. Time plays an important role in this legal drama, although at this early point in the film Stewart’s character is at a point where he’s primarily turned his time and attention to assorted hobbies such as fishing, playing the piano, and spending time with his friend McCarthy, and his assistant, Maida Rutledge (Eve Arden). The walls are painted halfway up to a chair-railing, with wallpaper decorating the wall from the chair-rail to the ceiling, giving a rather formal, faux-opulent feel to the space. He then takes the satchel into a kitchen, where he takes several fish out of it and places them into a sink with cold running water running over them. He has not removed his hat or jacket, but turns around to return his attention back to the note attached to the antlers.

He takes the note and heads down a hallway, turning on lights as he goes, until he enters a formal study. Floor to ceiling bookshelves line the walls behind him, lined with law books. Today, it’s almost a cliche to see a lawyer’s office lined with shelves containing legal texts: but regardless of when a story like this takes place, it’s these case study summaries of past precedents that makeup the heart of any lawyer’s practice. And in 1959 it’s a world that many watching a film like Anatomy of a Murder may not have glimpsed before.

If Biegler is our story’s hero, it seems his mentor McCarthy has plunged him headfirst into the hero’s journey without Biegler’s consent.