Artifact 03 Summary

Evidence (1977) by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan redefined narrative in photography by recontextualizing found images.

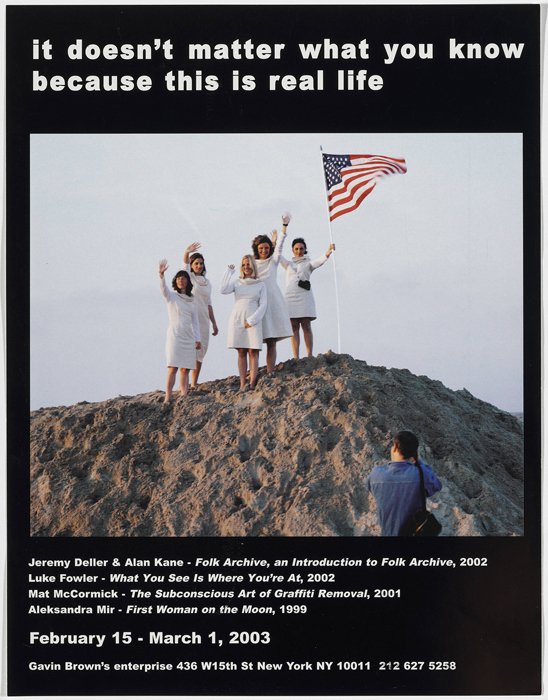

The 2015 exhibition Beyond Evidence at the Format International Photography Festival explored contemporary narrative strategies in photography.

22 artists presented diverse approaches to storytelling, questioning the truthfulness and veracity of images.

Key themes: decontextualization, participatory narratives, blending fact and fiction, and the limits of photographic representation.

Projects highlighted: collaborative storytelling with domestic workers, text-image integration, and the mythologizing of art forgers.

The exhibition challenges the idea of a single, objective narrative, emphasizing polyphony and viewer interpretation.

Origins and Impact of 'Evidence' (1977)

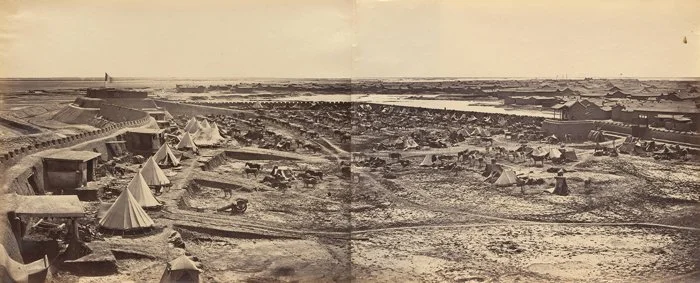

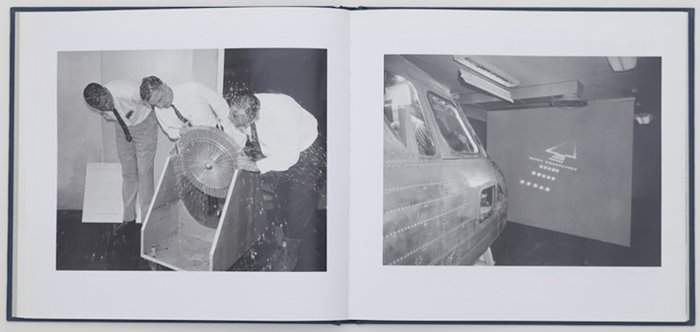

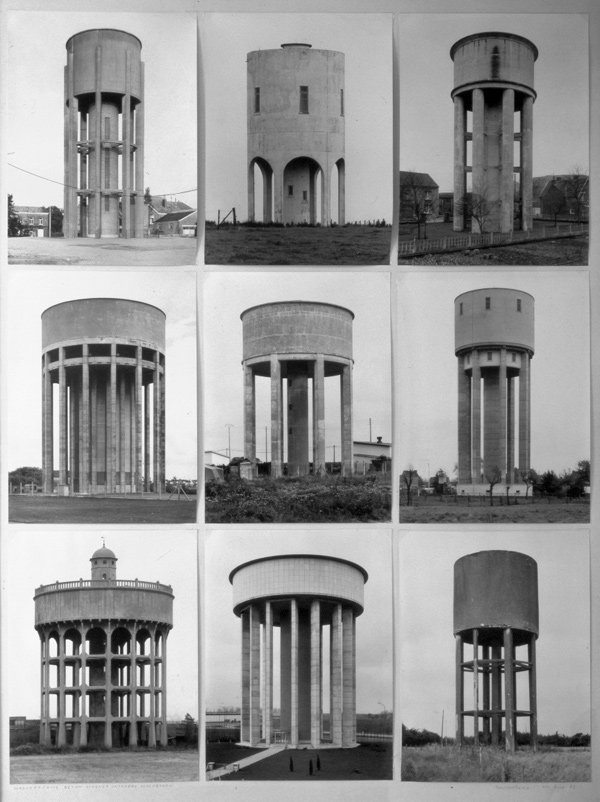

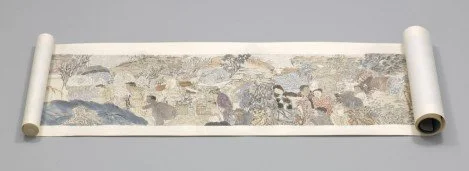

'Evidence' repurposed photographs from original contexts to create new visual narratives.

Book is now considered a seminal work in photography.

In 2015, 'Evidence' inspired an exhibition at the FORMAT International Photography Festival in the UK.

Exhibition titled 'Beyond Evidence' explored contemporary narrative approaches in photography.

Curated by Lars Willumeit and Louise Clements.

Exhibited at QUAD Arts Centre, Derby.

Beyond Evidence Exhibition: Themes and Curation

Presented 22 distinct narrative positions.

Focused on storytelling as an overarching theme.

Explored challenges visual artists face in storytelling.

Examined methods for presenting images and information in narratives.

Highlighted innovation in narrative techniques beyond traditional evidence.

Narrative Strategies and the Question of Truth

Exhibition explores diverse strategies for questioning narrative creation.

Term 'evidence' in title highlights concern with truthfulness.

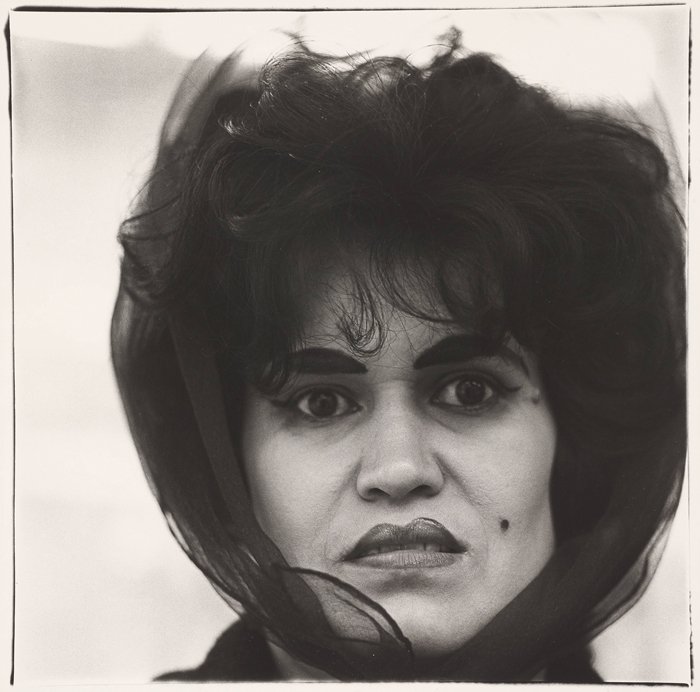

Photographers challenge the veracity of imagery.

Debate exists on photography's ability to provide meaningful narrative evidence.

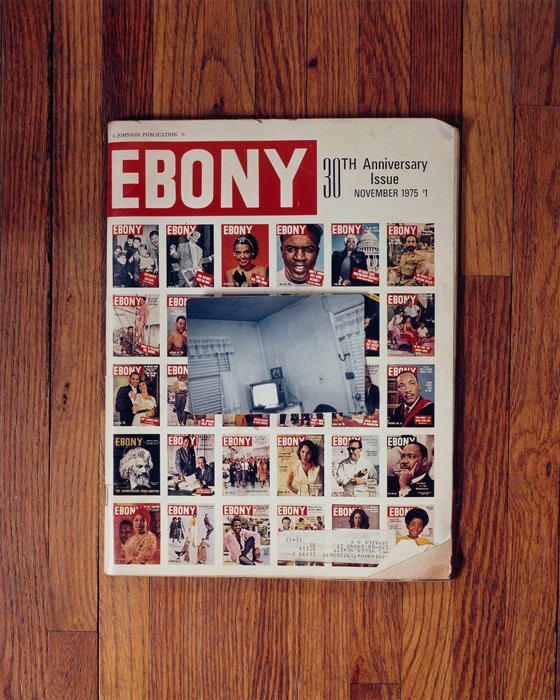

Book format, as used by Sultan and Mandel, is seminal in photography history.

Sultan and Mandel's approach inspires many young photographers.

California, especially the West Coast, was influential during that period.

Decontextualization and New Narratives in Photography

Group of artists, including Robert Heinecken and John Baldessari, worked with found photography.

Book from America influenced new approaches to photography in the group.

Book likely accessed via Creative Camera magazine.

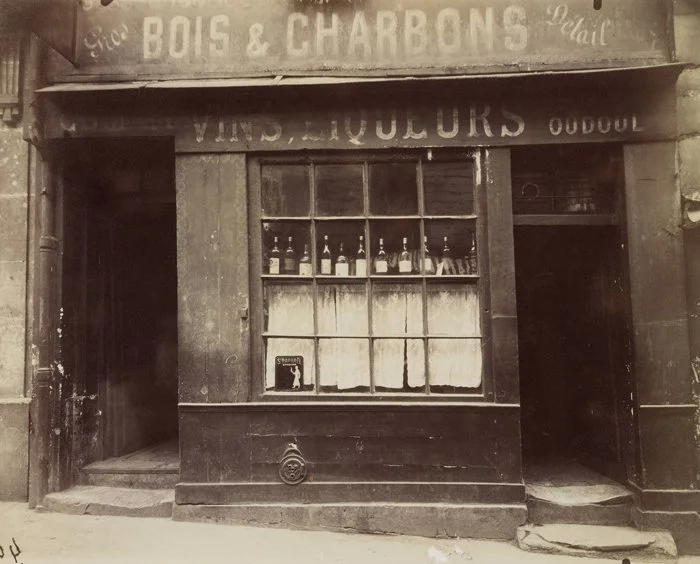

Book promoted decontextualizing images from various archives: commercial, company, governmental.

First exposure to functional images not created by famous photographers.

Images lacked titles and context, increasing fascination.

Shifted focus from well-known photographers to anonymous creators.

Inspired by Duchamp's concept that context defines art.

Adopted approach of using found photographs as art without alteration.

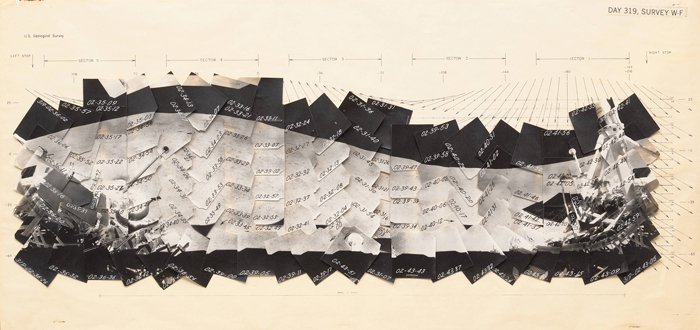

Artists reviewed approximately 2 million images, selected 59 for the book 'Evidence'.

Recontextualization of images created new poetic or narrative functions.

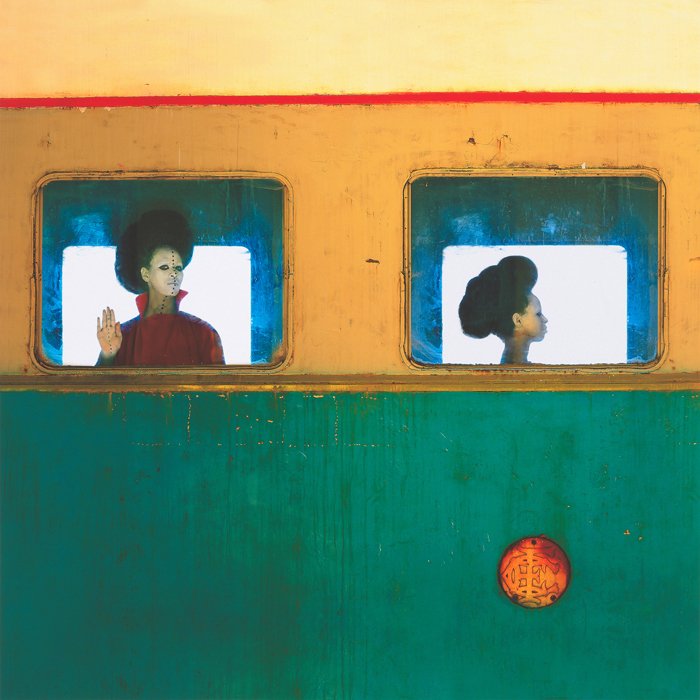

Poetic Narrative and Visual Storytelling

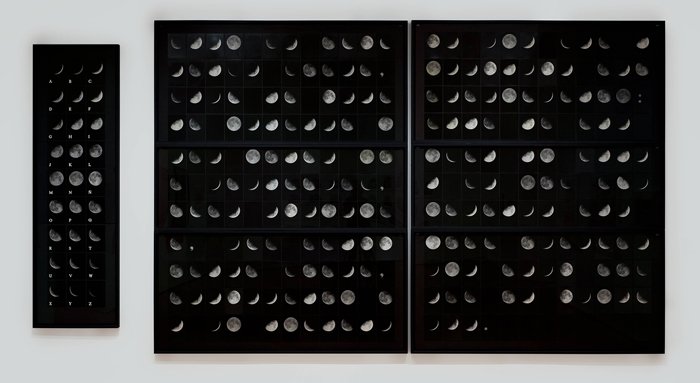

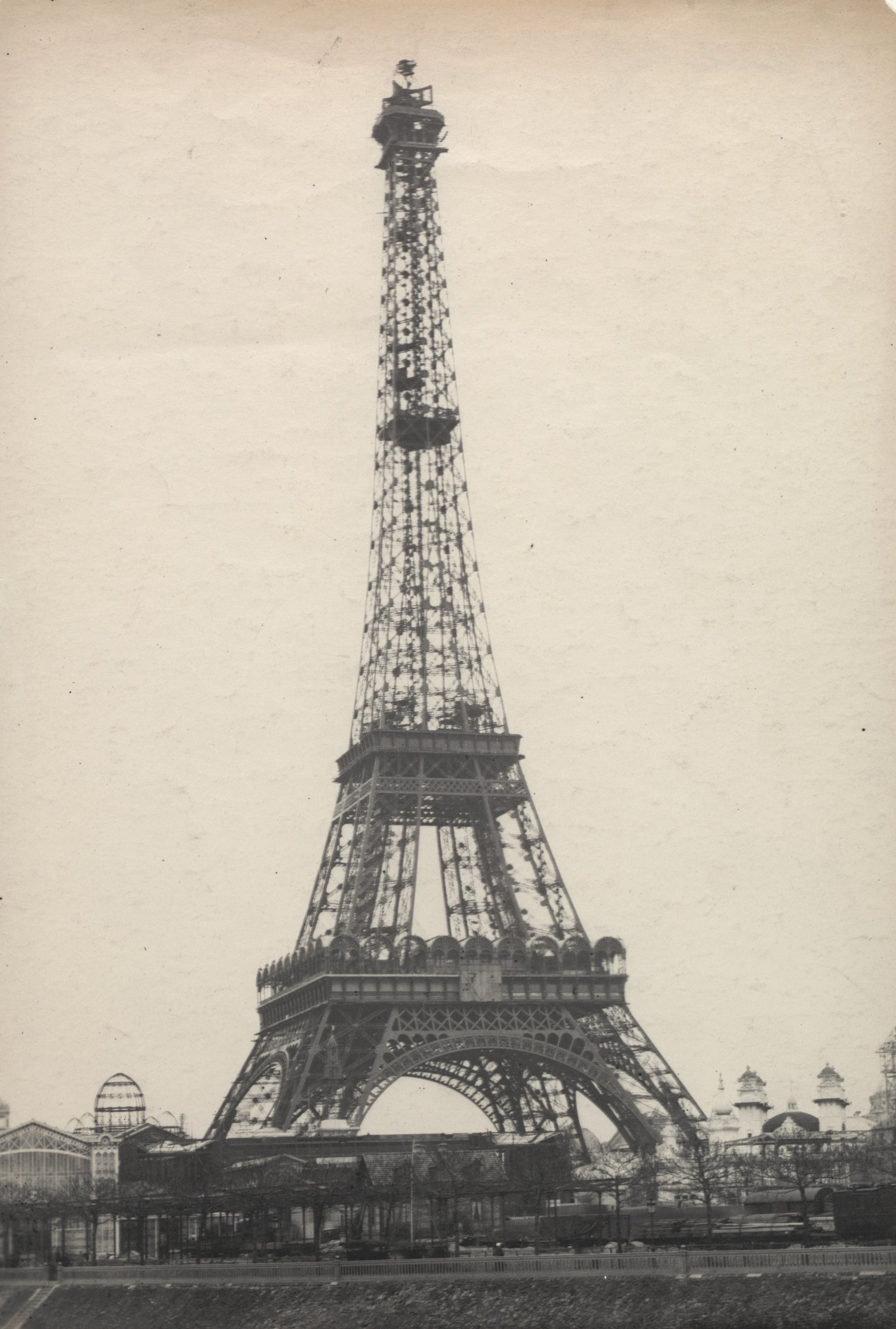

Placing images in new relationships creates new narratives.

Mandela and Sultan used double-page spreads to form poetic visual narratives.

Decontextualization removes images from original archival context.

Recontextualization places images into new sequences within books.

Double-page spreads establish inter-iconic relationships between images.

Sequencing spreads generates a non-linear visual narrative.

Photographs acquire new meanings through this process.

Original archival photographs become part of the creators' new work.

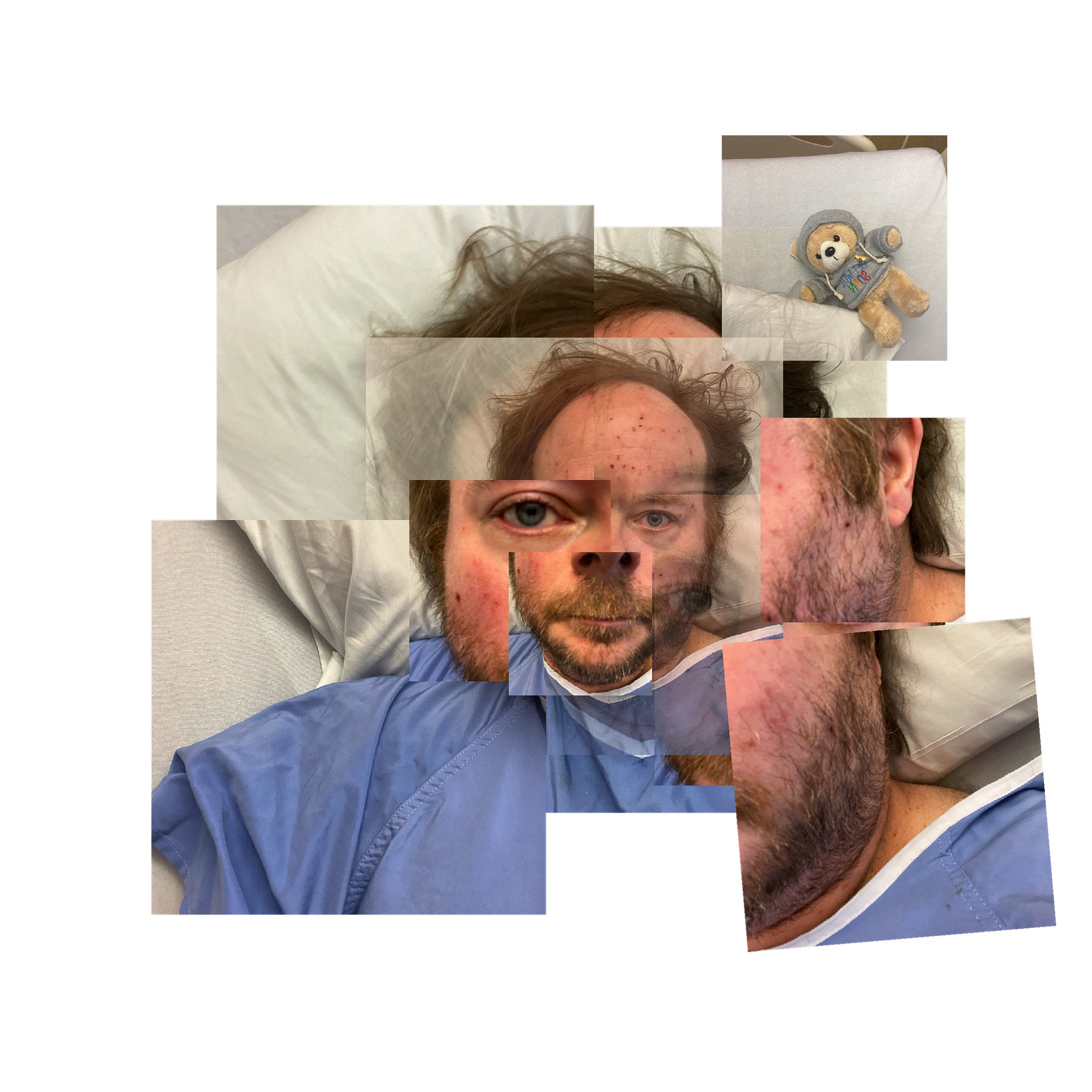

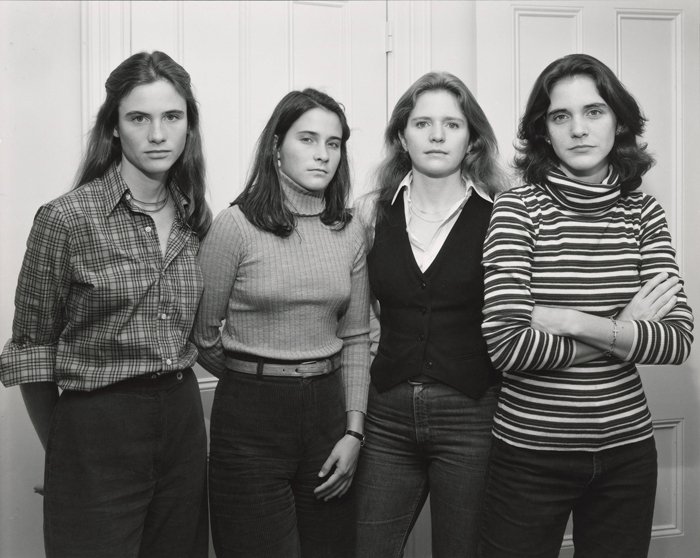

Participatory and Polyphonic Narratives: Worker Magazine

Worker Magazine Cooperative enables domestic workers to create their own photographs.

Focuses on open-ended, collaborative narratives rather than singular, linear stories.

Emphasizes participatory, collective, and polyphonic storytelling.

Narratives are co-created, not authored by a single voice.

Images serve as actors within a political movement for visibility and self-representation.

Viewers are invited to interpret and complete the narrative themselves.

Contrasts with Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s approach of transforming found images into personal work.

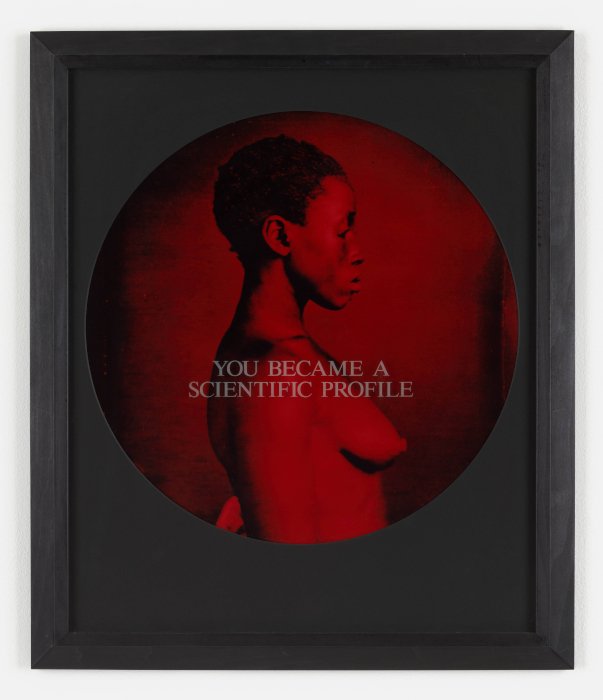

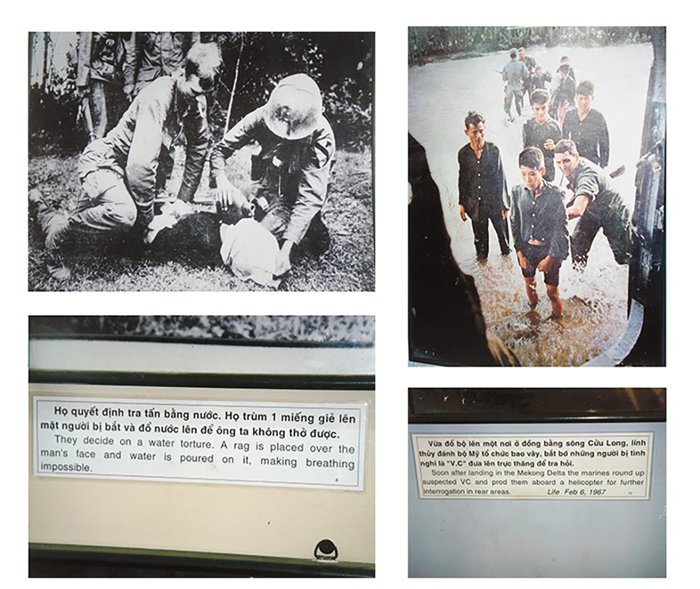

Limits of Photography and Text-Image Integration

Photographs have limitations in accurately transmitting certain information.

Documentary photographers often combine text and images to enhance storytelling.

Lucas Anzella integrates text, images, and web hyperlink-inspired graphic design.

Some information cannot be shown with pictures alone; some is weaker without visuals.

Anzella's project, 'The Many Moments of an M85 Xenon's Arrow Retraced,' uses the reverse trajectory of a cluster bomb as a metaphor.

Project traces connections from a bomb victim through various roles (miners, graphic designers, fuse engineers) to investment companies.

Deutsche Bank cited as an example of financial involvement in companies producing submunition fuses.

Many components and relationships in the story are not visible or photographable.

Photography alone cannot depict dense, interconnected relationships.

Anzella's work exemplifies artistic research into the limits of photographic storytelling.

Other artists in the exhibition and festival also address the challenge of telling complex, layered stories.

Blending Fact and Fiction: Case Studies of Conmen and Forgers

Seralina Mayhoffer and Sarah Pickering both address stories involving deception and identity.

Seralina Mayhoffer's work 'Dear Clark' focuses on con man Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, alias Clark Rockefeller.

Gerhartsreiter impersonated various identities, including a Rockefeller, brain surgeon, and actor, over 30 years in the US.

'Dear Clark' combines photographic interpretations, real documents, fictional elements, and staged photographs.

Project began as a portrait series; Mayhoffer wrote to Gerhartsreiter but received no reply.

Mayhoffer explores the concept of photography as a tool for deception, paralleling the con man's methods.

Work presents a non-hierarchical mix of fact and fiction, reflecting the elusive nature of the subject.

Project examines both the figure of the con man and Mayhoffer's own perceptions of deception.

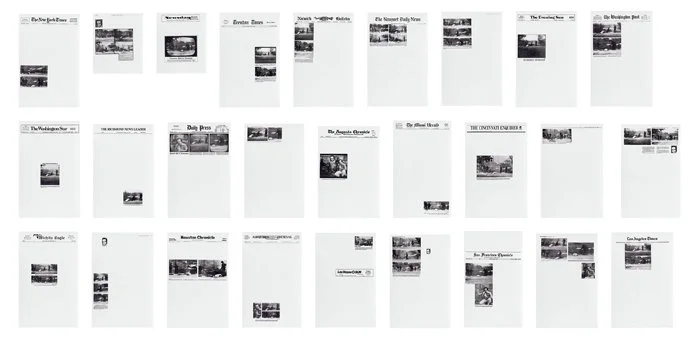

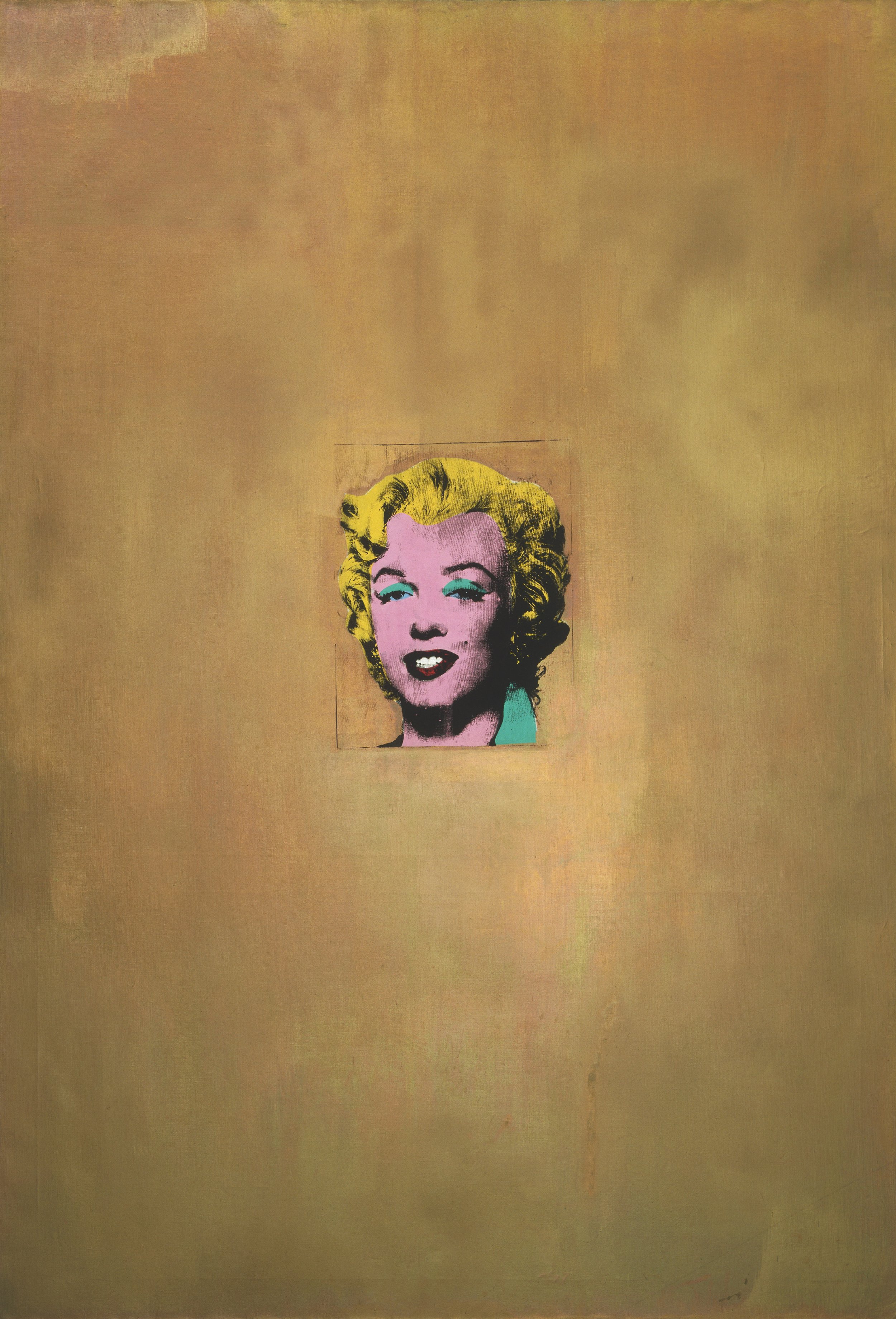

Mythologizing and Re-mythologizing in Art and Media

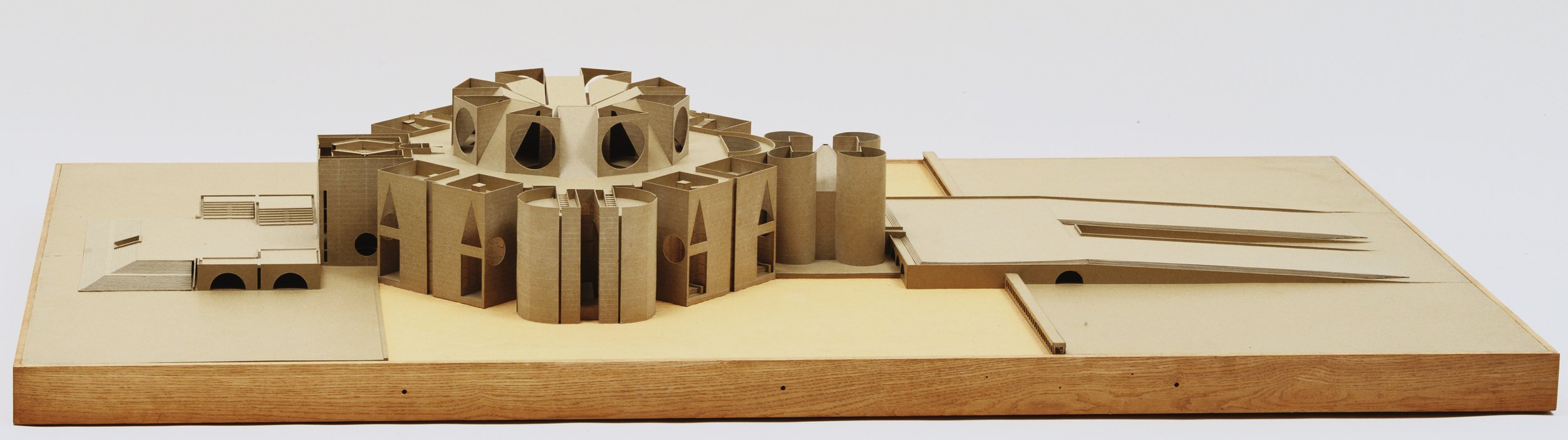

Sarah Pickering created an installation at Derby Museum for the Format Festival.

Installation juxtaposed works by forger Sean Greenhalgh, original Joseph Wright paintings, and works in Wright's style.

Exhibit included police evidence, TV props, and press clippings.

Explored how stories about forgers are recreated and mythologized by various actors (media, police, museums).

Newspaper reports and museum exhibitions each emphasized different aspects of Greenhalgh's life.

Sarah focused on narrative development from a single story, not on distinguishing real from fake.

Sean Greenhalgh forged a wide range of objects: Egyptian sculptures, Roman metalwork, Cubist paintings.

A forged Gauguin clay sculpture by Greenhalgh was acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago and featured in multiple books and exhibitions.

Despite being exposed as a fake, the sculpture's false history persists in archives and media.

Metropolitan Police's V&A Museum exhibition reconstructed Greenhalgh's workshop as a garden shed, reinforcing a mythologized narrative.

The shed narrative originated from media and dramatizations, not factual evidence.

Police and media contributed to the mythologizing of Greenhalgh as a working-class hero.

Uncertainty remains about Greenhalgh's use of his forgery profits.

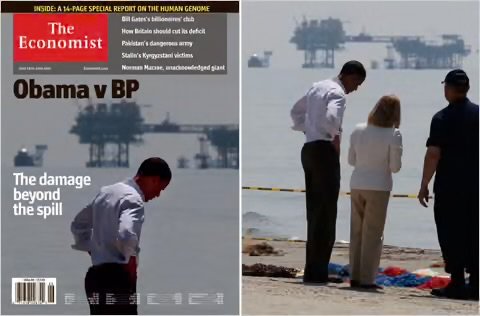

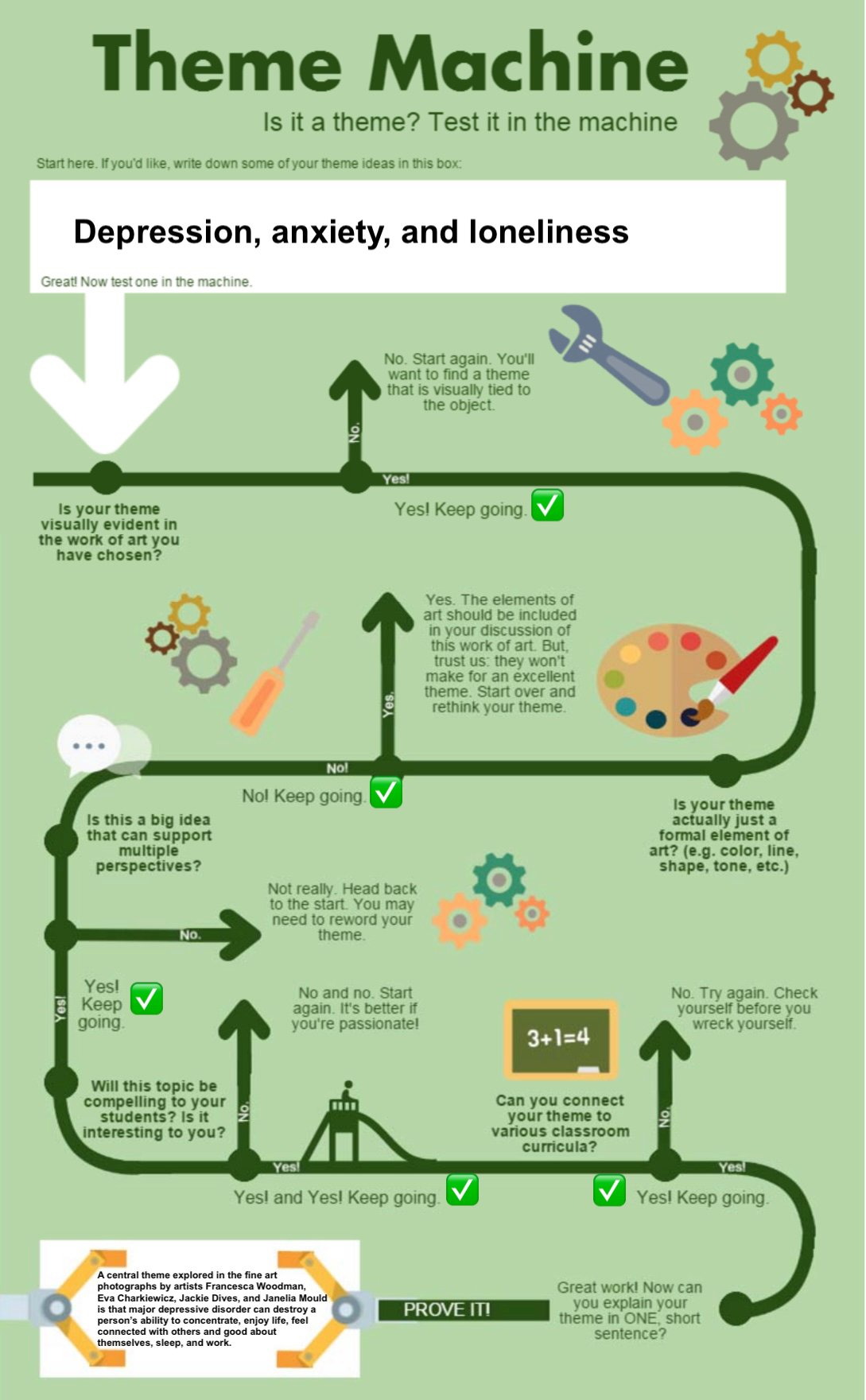

Truth, Trust, and the Role of the Viewer

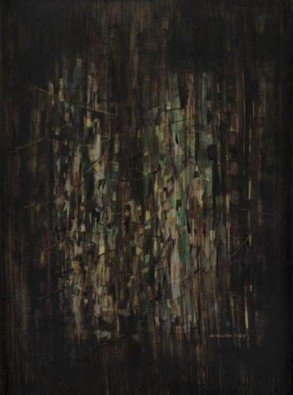

Seralina and Sarah mixed fact with fiction in their work.

Sputnik Collective fabricated a murder story from documentary archives.

Documentary photography does not present absolute truth.

Images and books cannot convey a singular, complete truth.

Exhibition questions trust in images removed from context.

Curatorial vision challenges the concept of truth in art.

Show highlights limits of didactic, singular narratives.

Multiple narratives provide a more accurate world depiction.

Collective awareness of storytelling's power is increasing.

Project reflects frustration with the idea of a single truth channel.

Photography presents only a surface, not full reality.

Desire for truth persists despite photography's limitations.

Forensic and evidence photography cannot guarantee objectivity.

Visual evidence is shaped by social processes and context.

Photographer acts as the first filter: topic, subject, aesthetics.

Exhibition presentation is the second filter.

Viewer reception is the third and most important filter.

Viewer is considered a collaborator in interpreting the work.

Ambiguity and Open-Ended Narratives

Artist has no control over viewer interpretation.

Viewers form independent judgments about images.

Narrative and sequence exist in photographic works.

Photographs arranged to create climax and denouement.

Narrative is ambiguous and open-ended by design.

Ambiguity is intentional artistic language.

Viewer perception of narrative is subjective and optional.