Part 1 - Introduction

1.1. Introduction to One and Another

Photography is a mechanical process. One consequence of this is that multiple images have been essential to the medium from its earliest days. Photographers can make multiple prints from a given negative, and can edit groups of images into series. Photographs can be gathered into albums and sequenced in books, and new meanings often emerge from these combinations. Technological advances have repeatedly facilitated the ease and speed with which photographers can produce multiple images, and the artistic possibilities have multiplied alongside them.

A photograph can be a singular, independent object, but what new possibilities and meanings occur when images are paired or combined? This week, we will explore the different ways artists have taken advantage of photography’s capacity for multiplicity—by weaving pictures together in photo books and albums; by grouping images to create a series or body of work; and by investigating the ways multiple images can be combined into new, indivisible works.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the impact of photography’s reproducibility.

Understand how photographs have been combined throughout the medium’s history to offer alternative approaches to individual images.

Consider how albums and books have expanded and facilitated access to photographs and photographic imagery.

VIDEO - MOMA. “Stephen Shore | HOW TO SEE the photographer with Stephen Shore.” YouTube, 25 Jan 2018.

VIDEO > MOMA. “How mass media representations shape us | Cindy Sherman | UNIQLO ARTSPEAKS.” YouTube, 13 Nov 2020.

Part 5 - Review & Respond

5.2. Discussion Prompts & Creative Challenges

5.2.a. Reflect on your responses to the art and ideas we explored this week. What was new or surprising to you?

As I explore photography as a student through my own emerging artistic practice, I’ve found that understanding and more importantly, actualizing the concept of a sequence or series of photographs for the purpose of connecting ideas and telling stories has become important for me. From this module, I’ve found that photography can make it easy to make a sequence or series (which Martian-Webster defines as representing “…a number of things, events, or people of a similar kind or related nature coming one after another; a group or a number of related or similar things, events, etc., arranged or occurring in temporal, spatial, or other order or succession.”) of photographs that share a thematic or narrative conceptual bond.

Specifically, Merriam-Webster describes how a sequence can be thought of as a list of elements with a particular order (the following of one thing after another; succession, or order of succession), a continuous or connected series, such as:

“a: an extended series of poems united by a single theme (a sonnet sequence);

b: three or more playing cards usually of the same suit in consecutive order of rank;

c: a succession of repetitions of a melodic phrase or harmonic pattern each in a new position;

…

f:

(1): a succession of related shots or scenes developing a single subject or phase of a film story;

(2): EPISODE (a usually brief unit of action in a dramatic or literary work; a developed situation that is integral to but separable from a continuous narrative; one of a series of loosely connected stories or scenes; an event that is distinctive and separate although part of a larger series).”

Photographer Taya Ivanova, in her article, “What is a Photo Series? (12 Cool Photo Series Ideas to Try)” for EXPERT PHOTOGRAPHY explains how:

“A photography series is a collection of images that are linked and showcased together. A series of photos will often have the same theme and have a conceptual bond. Sometimes they’re shot at the same location. And photo series are often edited in the same style to focus on coherence.

Photographer Drew Hopper, in his article, “Photo tip of the week: How to shoot a photo series” for AUSTRALIAN PHOTOGRAPHY relates the idea of shooting in a series to telling a story, as he describes how:

“Stories are integral to human culture and storytelling is timeless. In photographic practice, visual storytelling is often called a 'photo essay' or 'photo story'. It's a way for a photographer to narrate a story with a series of photographs.”

VIDEO > The Art of Photography. “SERIES BASED PHOTOGRAPHY.” YouTube, 22 Jun 2016.

Mary Warner Marien, in the 5th edition of her book, “Photography: A Cultural History” describes how:

“The idea of the photographic series—that is, of creating and arranging images in meaningful sequences—was increasingly adopted in historical, archeological, travel, scientific, medical, and even art photography. During the medium’s earliest years, compilations of dissimilar and unrelated images, such as those found in Lerebours’s Excursions Daguerriennes and Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, were prevalent. But as photography proliferated, arrangements of related images were published more frequently. Photographic series expanded the notion of photography from that of an image-making process to something akin to writing. Nineteenth-century albums and books containing interrelated pictures underscored the photographer’s skill in building up what the twentieth century would know as the photographic essay. Slowly, commentators began to concede that some photography—series, aesthetic endeavors, and scientific improvements—involved intellectual exertion, a claim that would serve to distance professional and serious amateur photographers from itinerant and part-time practitioners” (49).

Later, Warner Marien explains how photographic series have become a modern and contemporary tool of photographers:

“Many postwar photographers worked in extensive series based on life experiences, be they road trips or observations gained through insight and meditation. The scope of these series, dramatized by the photographer’s unique perspective on how to order the images, propelled the photographic book into prominence. The rhythm, connections, and contradictions of form and subject generated by sequenced images had a lasting impact on contemporary photographic practice” (355).

Finally, Maria Short, Sri-Kartini Leet, and Elisavet Kalpaxi, in their book, “Context and Narrative in Photography,” examine how Bernd & Hella Becher used their series to explore the German industrial landscape, describing how:

“The way in which an image is presented is an important aspect of the context in which it is seen and therefore interpreted. Size, shape and ordering of images are the main ingredients that inform how a series of images relate to each other or highlight the significance of a single image.

Typology sets, or series, are a simple but effective way of enabling the viewer to compare the detail within a group of photographs. Typology is simply the study of types. Photography can be used in a consistent manner to produce a set of related images, as with Jamie Sinclair’s images, and illuminate aspects of either the subject or conceptual approach. The presentation of the typology group, such as in a grid formation, can be integral to the interpretation and also an exercise in considering how viewers understand the relationships between one image and another within the exhibition space. The German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher photographed industrial buildings for over forty years, starting in 1959, and made black-and-white photographs of types of industrial structures using a large format camera, often exhibited in grid format. They employed a rigourously consistent way of working – each structure was photographed from a similar angle and under similar lighting conditions. In relation to their presentation, Michael Collins (2002) explains in Tate Magazine: ‘By placing photographs of similar subjects alongside each other, the individual differences emerge, making the fine details in each picture more noticeable, more distinct. Drawing on this, they began exhibiting the pictures as typologies... the typology was the work... a symphony of industrial structures.’ Presenting their work in a grid, as mentioned in chapter 1, ‘The Photograph’, was one of the methods the Bechers employed to draw attention away from documentary and toward form. In other bodies of work, such as Lalage Snow’s, noticing the ‘fine details’ is integral to the documentary function of the work” (97).

VIDEO > Michael Blackwood Productions. “BERND AND HILLA BECHER: 4 Decades [trailer].” YouTube, 15 April 2019.

5.2.b. Which of the artists or works particularly resonate with you or open up different perspectives on art or the world today?

Knowing that Frances Benjamin Johnston worked as a female commercial portrait photographer, as well as one of the first photojournalists, while pursuing a career as an artist resonated with me. From the discussion about her practice, it appears that she worked to bridge the gap between photography as being simply representational to existing as works of fine art. In the series of works she did for the Hampton Institute, she brought her experience as a commercial photographer to the table, in how she carefully composed the frame and directed the subjects appearing within it. This process would have allowed her to craft and design the vision she had for each photograph as well as for the entire series.

5.2.c. What new questions did this week raise for you?

This week did provide me with the opportunity to explore the idea of photographic series or sequences in greater detail. I am curious about what leads a photographer to the decision that multiple photographs could be shot to explore a concept, idea, story, or theme as opposed to using a single image to represent that concept, idea, story, or theme. As a student of photography, I understand how it can be more difficult to edit a series down so one is using less photographs, or even a single photograph, to communicate a photographer’s overall intent. This is also true for writing, as a common exercise for writers is to write something, and then go back to edit it by cutting it in half, and still conveying the emotions and ideas of the original piece. A similar exercise for screenwriters or playwrights is to write a scene with dialogue, and then cut the amount of dialogue in half, and then in half again, and then without any dialogue. I think when one works with film photography, you definitely think more as you are usually limited by how many images you can shoot: 24-36 images on a 35mm roll of film. Maybe a dozen with medium format film, and then just a single plate with large format film cameras. I think it can be a good practice for any creative person - to learn how to work with less. But then, depending on the subject, if you are the Bechers for example, photographing many industrial buildings in Germany, then the strength comes through the repetition of the images, combined with how they are composed, and displayed.

Review…

Some of the ways artists take advantage of photography's capacity for multiplicity include:

By weaving pictures together in photo books and albums;

By grouping images to create a series or body of work; and

By combining multiple images into new, indivisible works.

Zoe Leonard uses order and repetition to build a narrative in her series, Analogue.

For the series, Circulation: Date, Place, Events, Takuma Nakahira did not take and meticulously compose the photographs several years before displaying them at the Seventh Paris Biennale.

Frances Benjamin Johnston's The Hampton Album:

Featured photographs used to promote the work of the Hampton Institute;

Saw Frances Benjamin Johnston depict both vocational and academic activities at the Institute; and

Saw it’s photographs exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900.

Leslie Hewitt likes to "explore the limits of a single photograph, a single perspective" by layering images, objects and materials and photographing them.

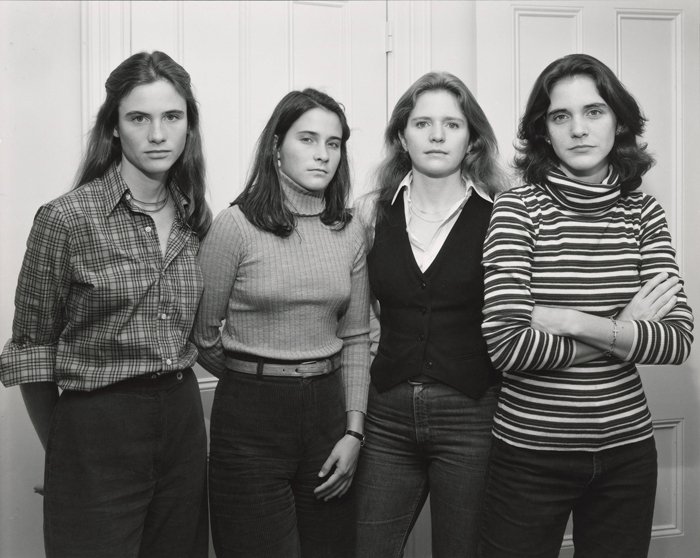

The following is consistent about all the photographs in Nicholas Nixon's series The Brown Sisters:

The sisters always stand in the same order;

Nicholas Nixon always uses an 8 × 10 inch view camera;

Each year one photograph is added to the series; and

Nicholas Nixon's wife always poses for the photos.

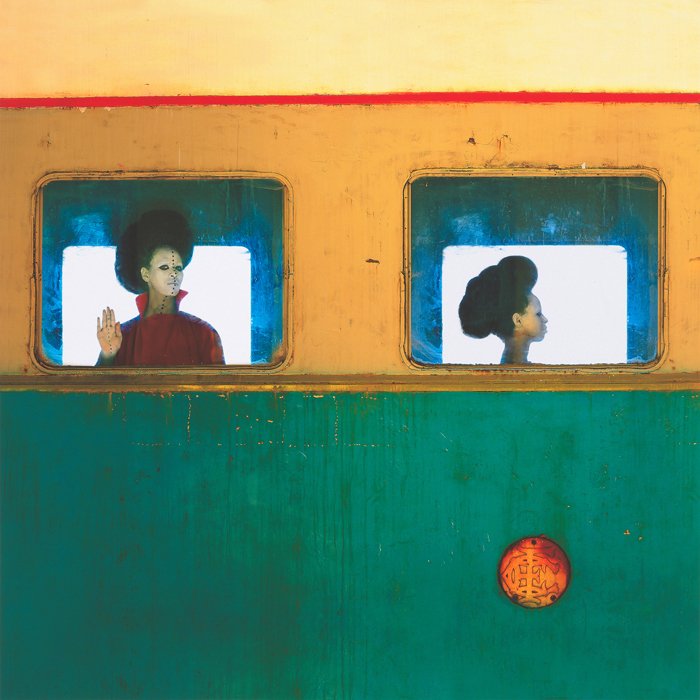

The Departure and All in One by Aida Muluneh both belong to the series The World is 9.

Sohrab Hura's series Snow:

refers to the history of violence in

Kashmir;

show the passage of time through the lens of changing seasons; and

Saw Hura listen to the stories of people he met in Kashmir to create the series,

Books have served as the source material for Iñaki Bonillas' series Marginalia.

The photograph Trolley -New Orleans by Robert Frank:

was included in the photo book The Americans 1958);

depicts a segregated bus with white

passengers seated toward the front and

Black passengers toward the back; and

was taken only weeks before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Zoe Leonard. Analogue. 1998–2009. Chromogenic color prints and gelatin silver prints, each 11 × 11" (27.9 × 27.9 cm).

Detail from Zoe Leonard. Analogue. 1998-2009.

Takuma Nakahira. C-177 from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events. 1971. Gelatin silver print, printed 2013, 12 5/8 × 18 7/8" (32.1 × 48 cm).

Takuma Nakahira. C-084 from the series Circulation: Date, Place, Events. 1971. Gelatin silver print, printed 2013, 12 5/8 × 18 7/8" (32.1 × 48 cm).

Frances Benjamin Johnston. Stairway of the Treasurer's Residence: Students at Work from The Hampton Album. 1899–1900.

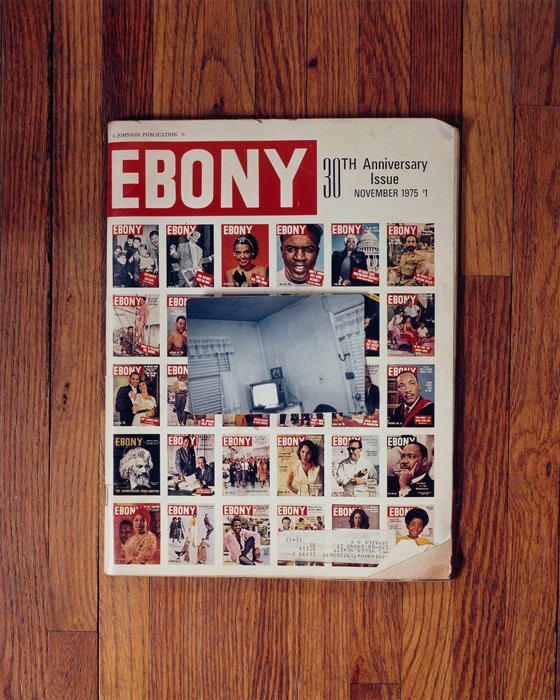

Leslie Hewitt. Riffs on Real Time. 2002–05. Chromogenic color print, 30 × 24" (76.2 × 61 cm).

Nicholas Nixon. The Brown Sisters, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 1977. Gelatin silver print, 7 11/16 × 9 11/16" (19.6 × 24.5 cm).

Nicholas Nixon. The Brown Sisters, Truro, Massachusetts. 2011. Gelatin silver print, 17 15/16 × 22 5/8" (45.6 × 57.5 cm).

Aïda Muluneh. The Departure. 2016. Pigmented inkjet print, 31 1/2 × 31 1/2" (80 × 80 cm).

Sohrab Hura. Untitled from the series Snow. 2015–ongoing. Pigmented inkjet print, 24 x 24" (61 x 61 cm).

Iñaki Bonillas. Marginalia 7. 2019. Pigmented inkjet print, 50 13/16 × 43 5/16" (129 × 110 cm).

Robert Frank. Trolley–New Orleans. 1955. Gelatin silver print, 9 1/16 × 13 3/8" (23.1 × 34 cm).