Part 1 - Introduction

1.1. Introduction to Documents and the Documentary

Because of photography’s inextricable connection to the real world—light sensitive film records what is before the camera’s lens—many descriptive photographs are considered documents, and the mode of making them is often called “documentary.” We’re going to explore work by many different makers across eras that has engaged with this idea to help build an appreciation for just how complicated it can be. Generations of photographers have turned their cameras to the world around them with the aim of taking pictures that record, remember, or bear witness. In the twentieth century, many photographers made images in the service of larger social causes. Newspapers and magazines came to rely on photographic illustrations to underscore the meaning of their stories and, conversely, text was called upon to shape viewers’ understanding of what they were seeing.

By the 1960s, many photographers began to feel constrained by the editorial control imposed by the popular press. They sought other outlets for sharing their work including publishing their own books. This coincided with the emergence of documentary projects that were intentionally inflected with personal meaning, made to question and subvert the perceived truthfulness of the medium or call attention to its political, social, and ethical complexities. Today, photographers continue to use the camera as a means of documenting the world, acknowledging that their images are not fixed statements of fact but, rather, that they may be read and interpreted in many different ways.

Learning Objectives

Analyze the reliability of photographs and the ways photographers reveal, manipulate, and critique truth.

Examine how words in and around photographs impact our understanding of them.

Compare the ways photographers have used the documentary style for personal expression and in service to larger social causes.

ARTIFACT 01 > MOMA. “Sarah Meister: Seeing Through Photographs.” YouTube, 10 Feb 2017.

Artifact 01 Summary

Photographs are often mistakenly equated directly with their subjects, but their meaning lies in the differences—scale, dimensionality, color—between subject and image.

Since its invention, photography has served a documentary function, recording reality much like drawing or etching once did.

The 1967 "New Documents" exhibition, organized by John Tchaikovsky, highlighted a shift: photographers like Arbus, Winogrand, and Friedlander used documentary style for personal expression rather than objective record.

Gary Winogrand's iconic photograph (1973) exemplifies how choices in framing, proximity, and medium transform a scene into a layered metaphor.

Every photographer's choices—from camera type to sharing method—shape the final image, distinguishing it from the original subject and revealing the artist's intent.

Photograph Subject vs. Meaning: The Tension in Differences

Photograph's subject often equated with its meaning.

Depicted object rarely matches photograph in scale, dimensionality, or color.

Differences between subject and photograph create tension and meaning.

Photography’s Documentary Function Since Inception

Photography invented as a means to record visual information.

Previously, drawing, etching, or sketching served this recording function.

Photograph's documentary function present since its inception.

The 1967 'New Documents' Exhibition and Its Impact

John Tchaikovsky organized 'New Documents' in 1967.

Exhibition combined three leading suggestions in contemporary photography.

Photographers did not aim to change the world.

Work was not client-driven.

Images served no external purpose beyond their own creation.

Documentary Clarity vs. Personal Expression in Photography

Traditional documentary photography required clarity and sharp focus.

Arbus, Winogrand, and Friedlander used handheld black-and-white photography.

They applied documentary techniques to personal subject matter.

Gary Winogrand’s Iconic Photograph: Technical Details

Photograph by Gary Winogrand entered collection in 1973.

Represents classic mid-to-late 20th-century print.

Created from 35mm negative.

Enlarged to exhibition scale.

Printed on gelatin silver paper.

Print was trimmed after printing.

Interpreting Winogrand: Subject, Metaphor, and Artistic Choices

Gary Winogrand photographed a blonde woman and an African-American man with two well-dressed monkeys in Central Park.

Image functions as both a literal subject and a metaphor.

Winogrand's choices include camera distance and framing.

Use of 35mm camera enables spontaneous street photography.

Photograph captures fleeting, candid street moments.

Photographic Choices: Framing, Medium, and Artistic Production

Photographers make choices in framing, camera selection, and print type.

Sharing methods influence the final image's perception.

Each choice differentiates the photograph from its subject.

Photographic process creates a distinction between subject and final image.

ARTIFACT 02 > International Center of Photography. “2023 Infinity Award: Documentary Practice and Visual Journalism - Zora J. Murff.” YouTube, 30 Mar 2023.

Artifact 02 Summary

Art as a lens: Murff uses art, especially photography, to explore and critique white supremacy and the realities of being Black in America.

Historical trauma: References to Michael Brown's murder, spectacle lynching, and the impact of redlining and segregation.

Structural violence: Art interrogates systems like the juvenile justice system and the school-to-prison pipeline.

Personal narrative: The speaker shares experiences of poverty, class mobility, and complex family relationships.

Cultural identity: Explores the performance of Black masculinity and the significance of cultural markers.

Liberation and hope: Emphasizes the need for collective action and critical questioning to achieve change.

Artistic Identity and Racial Context

Identifies as an artist who is Black in a race-conscious society.

Art examines the pathology of white supremacy.

Uses photography, imagery, and art to explore related realities.

Impact of Michael Brown's Murder and Spectacle Lynching

Michael Brown murdered by Darren Wilson in 2014, Ferguson, Missouri.

Body left on Canfield Drive, visible to community.

Incident evoked history of spectacle lynching.

Event prompted personal decision to stop working.

Photography, Imagery, and the Pathology of White Supremacy

Camera used to create images enforcing racial hierarchies.

Images historically used to shame Black people.

Visual media perpetuates stereotypes and beliefs imposed by white-dominated systems.

Images reinforce and sustain discriminatory actions and ideologies.

Personal realization of the impact and intent behind such imagery.

Structural Violence and Black Resilience

Addresses multiple levels of structural violence.

Documents individuals in locations marked by police oppression and segregation.

Highlights both experiences of oppression and survival strategies.

Emphasizes resilience and adaptation within Black communities in America.

Frames survival and perseverance as central to Black American life.

Juvenile Justice System and Stigmatization

Initial work involved juveniles in the criminal justice system.

Photography used within the system for categorization and stigmatization.

Portraiture, Anonymity, and Representation

Photographer intentionally avoided showing child's face in portrait session.

Encounter prompted negotiation about subject's representation.

Child's gesture (scratching neck) influenced composition.

Session raised questions about subject's preferred visibility.

Anonymity in portrait parallels system's removal of personal aspects.

Other visual elements compensated for lack of facial identity.

School-to-Prison Pipeline and Personal Revelation

Report discussed school-to-prison pipeline statistics.

Statistics personalized by relating to own child.

Realization led to valuing art as a solution or intervention.

Redlining, Urban Policy, and Economic Disenfranchisement

"At No Point In Between" set in North Omaha, Nebraska.

Area characterized by vacant lots, condemned buildings, and homes.

1930s: Federal government implemented redlining, a form of government-endorsed segregation.

Redlining assigned low (D) ratings to predominantly Black neighborhoods, reducing land value.

Low ratings discouraged investment in these neighborhoods.

North Freeway construction rerouted from white to Black neighborhood due to community opposition.

Freeway construction caused mass exodus from Black neighborhood.

Abandonment of homes and businesses followed, reducing economic activity.

Economic disenfranchisement resulted from policy and infrastructure decisions.

Redlining and infrastructure projects described as mechanisms of systemic racial oppression.

Socioeconomic Mobility and Racial Identity

Grew up in poverty.

Remained poor through mid to late 20s.

Secured a teaching job.

Achieved success in the art world.

Recently experienced socioeconomic mobility.

Reflected on class mobility and racial identity in artwork.

Highlighted societal perceptions of a Black man achieving wealth (e.g., driving a 7 Series).

Acknowledged racial identity as a persistent boundary despite economic advancement.

Masculinity, Performance, and Cultural Markers

Described wearing a foil grill, bare-chested, with a chain.

Explored masculinity as a performance within black culture.

Identified the grill as a significant cultural marker.

Suggested the grill serves as a way to adopt or display a certain identity.

Family, Vulnerability, and Healing

Speaker described efforts to address personal marginalization.

Visited father in Mississippi after 10 years of no contact.

Father left when speaker was 5 or 6 years old.

Relationship characterized as disjointed and disconnected; described as strangers.

Primary goal of visit: create a portrait of father.

Murff describes the fear he experienced regarding acceptance by father.

Upon arrival, immediate hug exchanged, conveying unconditional love.

Acknowledged father's past harmful actions toward family and others.

Murff maintains love for father due to early lessons in love.

Experience described as profound and transformative, unlocking personal growth.

True Colors: Affirmations in a Crisis

Book titled 'True Colors or Affirmations in a Crisis'.

Described as a manual for understanding Black identity in America.

Structured around personal life stories and experiences.

Exposes inner thoughts and personal history.

Includes first self-portrait from initial photography class.

Work spans entire artistic career.

Connecting Past and Present: Historical Memory and Public Symbols

Connected historical and recent events: Watts riots (1990s), Minnesota riots after George Floyd's murder (2020).

Emphasized critical analysis of public images and monuments.

Referenced Christopher Columbus statue in Syracuse, NY, depicting him standing on severed heads of indigenous people.

Highlighted public monuments as reflections of societal value systems.

Innovation in Art Books: Embedding Rap Lyrics

Gatefold spread featured in book.

Inside contains lyrics to a rap track by Tay Butler (former graduate).

Leslie Martin (Aperture) stated this is the first rap track embedded in an Aperture book.

Book represents a literal and symbolic first for Aperture.

Liberation, Conspiracy, and the Call for Change

Murff describes personal awakening to societal realities.

Section titled 'Liberation.'

Identifies blackness in America as a central theme.

Highlights anti-black violence and oppression as systemic issues.

References historical and ongoing injustices: slavery, incarceration, lynching, redlining.

Describes these injustices as forms of black genocide.

Argues change requires a critical mass advocating for rights.

Views art as a tool for social change and personal liberation.

ARTIFACT 03 > TroikaEditions. “FORMAT 15 Beyond Evidence.” YouTube, 6 Apr 2015.

Artifact 03 Summary

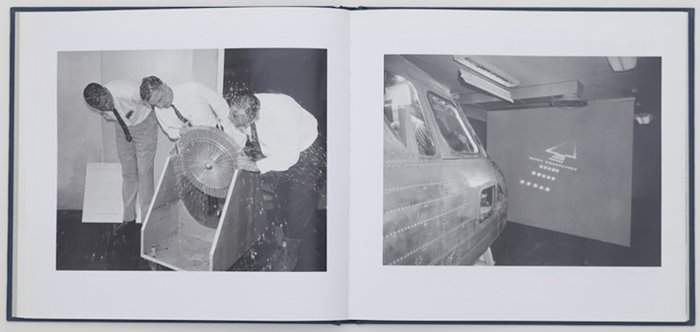

Evidence (1977) by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan redefined narrative in photography by recontextualizing found images.

The 2015 exhibition Beyond Evidence at the Format International Photography Festival explored contemporary narrative strategies in photography.

22 artists presented diverse approaches to storytelling, questioning the truthfulness and veracity of images.

Key themes: decontextualization, participatory narratives, blending fact and fiction, and the limits of photographic representation.

Projects highlighted: collaborative storytelling with domestic workers, text-image integration, and the mythologizing of art forgers.

The exhibition challenges the idea of a single, objective narrative, emphasizing polyphony and viewer interpretation.

Origins and Impact of 'Evidence' (1977)

In 1977, Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan published 'Evidence' in California.

'Evidence' repurposed photographs from original contexts to create new visual narratives.

Book is now considered a seminal work in photography.

In 2015, 'Evidence' inspired an exhibition at the FORMAT International Photography Festival in the UK.

Exhibition titled 'Beyond Evidence' explored contemporary narrative approaches in photography.

Curated by Lars Willumeit and Louise Clements.

Exhibited at QUAD Arts Centre, Derby.

Beyond Evidence Exhibition: Themes and Curation

Presented 22 distinct narrative positions.

Focused on storytelling as an overarching theme.

Explored challenges visual artists face in storytelling.

Examined methods for presenting images and information in narratives.

Highlighted innovation in narrative techniques beyond traditional evidence.

Narrative Strategies and the Question of Truth

Exhibition explores diverse strategies for questioning narrative creation.

Term 'evidence' in title highlights concern with truthfulness.

Photographers challenge the veracity of imagery.

Debate exists on photography's ability to provide meaningful narrative evidence.

Book format, as used by Sultan and Mandel, is seminal in photography history.

Sultan and Mandel's approach inspires many young photographers.

California, especially the West Coast, was influential during that period.

Decontextualization and New Narratives in Photography

Group of artists, including Robert Heinecken and John Baldessari, worked with found photography.

Book from America influenced new approaches to photography in the group.

Book likely accessed via Creative Camera magazine.

Book promoted decontextualizing images from various archives: commercial, company, governmental.

First exposure to functional images not created by famous photographers.

Images lacked titles and context, increasing fascination.

Shifted focus from well-known photographers to anonymous creators.

Inspired by Duchamp's concept that context defines art.

Adopted approach of using found photographs as art without alteration.

Artists reviewed approximately 2 million images, selected 59 for the book 'Evidence'.

Recontextualization of images created new poetic or narrative functions.

Poetic Narrative and Visual Storytelling

Placing images in new relationships creates new narratives.

Mandela and Sultan used double-page spreads to form poetic visual narratives.

Decontextualization removes images from original archival context.

Recontextualization places images into new sequences within books.

Double-page spreads establish inter-iconic relationships between images.

Sequencing spreads generates a non-linear visual narrative.

Photographs acquire new meanings through this process.

Original archival photographs become part of the creators' new work.

Participatory and Polyphonic Narratives: Worker Magazine

Worker Magazine Cooperative enables domestic workers to create their own photographs.

Focuses on open-ended, collaborative narratives rather than singular, linear stories.

Emphasizes participatory, collective, and polyphonic storytelling.

Narratives are co-created, not authored by a single voice.

Images serve as actors within a political movement for visibility and self-representation.

Viewers are invited to interpret and complete the narrative themselves.

Contrasts with Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan’s approach of transforming found images into personal work.

Limits of Photography and Text-Image Integration

Photographs have limitations in accurately transmitting certain information.

Documentary photographers often combine text and images to enhance storytelling.

Lucas Anzella integrates text, images, and web hyperlink-inspired graphic design.

Some information cannot be shown with pictures alone; some is weaker without visuals.

Anzella's project, 'The Many Moments of an M85 Xenon's Arrow Retraced,' uses the reverse trajectory of a cluster bomb as a metaphor.

Project traces connections from a bomb victim through various roles (miners, graphic designers, fuse engineers) to investment companies.

Deutsche Bank cited as an example of financial involvement in companies producing submunition fuses.

Many components and relationships in the story are not visible or photographable.

Photography alone cannot depict dense, interconnected relationships.

Anzella's work exemplifies artistic research into the limits of photographic storytelling.

Other artists in the exhibition and festival also address the challenge of telling complex, layered stories.

Blending Fact and Fiction: Case Studies of Conmen and Forgers

Seralina Mayhoffer and Sarah Pickering both address stories involving deception and identity.

Seralina Mayhoffer's work 'Dear Clark' focuses on con man Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, alias Clark Rockefeller.

Gerhartsreiter impersonated various identities, including a Rockefeller, brain surgeon, and actor, over 30 years in the US.

'Dear Clark' combines photographic interpretations, real documents, fictional elements, and staged photographs.

Project began as a portrait series; Mayhoffer wrote to Gerhartsreiter but received no reply.

Mayhoffer explores the concept of photography as a tool for deception, paralleling the con man's methods.

Work presents a non-hierarchical mix of fact and fiction, reflecting the elusive nature of the subject.

Project examines both the figure of the con man and Mayhoffer's own perceptions of deception.

Mythologizing and Re-mythologizing in Art and Media

Sarah Pickering created an installation at Derby Museum for the Format Festival.

Installation juxtaposed works by forger Sean Greenhalgh, original Joseph Wright paintings, and works in Wright's style.

Exhibit included police evidence, TV props, and press clippings.

Explored how stories about forgers are recreated and mythologized by various actors (media, police, museums).

Newspaper reports and museum exhibitions each emphasized different aspects of Greenhalgh's life.

Sarah focused on narrative development from a single story, not on distinguishing real from fake.

Sean Greenhalgh forged a wide range of objects: Egyptian sculptures, Roman metalwork, Cubist paintings.

A forged Gauguin clay sculpture by Greenhalgh was acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago and featured in multiple books and exhibitions.

Despite being exposed as a fake, the sculpture's false history persists in archives and media.

Metropolitan Police's V&A Museum exhibition reconstructed Greenhalgh's workshop as a garden shed, reinforcing a mythologized narrative.

The shed narrative originated from media and dramatizations, not factual evidence.

Police and media contributed to the mythologizing of Greenhalgh as a working-class hero.

Uncertainty remains about Greenhalgh's use of his forgery profits.

Truth, Trust, and the Role of the Viewer

Seralina and Sarah mixed fact with fiction in their work.

Sputnik Collective fabricated a murder story from documentary archives.

Documentary photography does not present absolute truth.

Images and books cannot convey a singular, complete truth.

Exhibition questions trust in images removed from context.

Curatorial vision challenges the concept of truth in art.

Show highlights limits of didactic, singular narratives.

Multiple narratives provide a more accurate world depiction.

Collective awareness of storytelling's power is increasing.

Project reflects frustration with the idea of a single truth channel.

Photography presents only a surface, not full reality.

Desire for truth persists despite photography's limitations.

Forensic and evidence photography cannot guarantee objectivity.

Visual evidence is shaped by social processes and context.

Photographer acts as the first filter: topic, subject, aesthetics.

Exhibition presentation is the second filter.

Viewer reception is the third and most important filter.

Viewer is considered a collaborator in interpreting the work.

Ambiguity and Open-Ended Narratives

Artist has no control over viewer interpretation.

Viewers form independent judgments about images.

Narrative and sequence exist in photographic works.

Photographs arranged to create climax and denouement.

Narrative is ambiguous and open-ended by design.

Ambiguity is intentional artistic language.

Viewer perception of narrative is subjective and optional.

Part 5 - Review & Respond

5.2. Discussion Prompts & Creative Challenges

5.2.a. Reflect on your responses to the art and ideas we explored this week. What was new or surprising to you?

I feel it’s important to remember how the “documentary in photography” is a subject that reflects on two considerations. First, it reflects on what it means for a photographer to make a photograph. That is, it reflects on how the meaning conveyed by a photograph will always be impacted by the choices a photographer makes when shooting and editing it. Secondly, documentary photographs are also impacted by how they are displayed and discussed.

Which of the artists or works particularly resonate with you or open up different perspectives on art or the world today?

Anna Atkins’s work stands out for both its aesthetic beauty and contribution to botany. Her use of the cyanotype process allowed her to make impressions of the ferns she was studying rather than the drawings that had been done before. It’s also inspiring to learn that she is considered the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographic images, and may have been the first woman to create a photograph.

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s work, Evidence, was a book published with archival photographs that were not produced by Sultan and Mandel. Their work explores the idea of context and how it impacts the meaning behind both individual photographs and photographs presented together as a part of a series (in this case, a book). Specifically, the photos were taken out of their original contexts, and placed into new ones without any other reference as to where or when the photographs were taken. The photos also speak to the idea that although they are of events that actually happened, but as a viewer looks at the work they are bringing their own context to bear when determining what the photographs might mean.

What new questions did this week raise for you?

Photography has always had the potential and the ability to capture and document events around the globe. And today, more than ever before, with the availability of digital cameras of high quality built into small hand held smart phones, events large and small, can be documented and sent out to the world within minutes, even seconds. Even many high quality digital cameras, can be paired to a smartphone, tablet, or computer to allow a photo to be downloaded and redistributed very easily.

In 2011, the revolution in Egypt, often referred to as the Arab Spring, is considered to be the world’s first smartphone revolution as they played an integral role in getting the story out about what was taking place.

That same year, in Vancouver, Canada, many people were able to capture and distribute images and videos of the riot that broke out in the aftermath of the NHL Stanley Cup Playoff loss of the Vancouver Canucks to the Boston Bruins. Bystanders to actual rioters posted images to social media, which law enforcement were able to use to identify and charge those who took part in the looting and destruction of stores, cars and other property. But there have been questions about some photos, and whether they faithfully represent what happened. For example, one famous photo shows a couple on the ground kissing. Some have questioned whether this was a decisive moment that was captured.

https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2011/jun/17/vancouver-kiss-couple-riot-police

Ultimately, it’s the almost universal accessibility of photography today has really brought new meaning to the idea of documentary photography and the citizen journalist.

5.2.b. Creative Challenge: Cropping Photographs

How does the way a photograph is cropped affect how we connect with the subject of the image? For example, in Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, the focus on the mother’s face may help viewers to empathize more deeply with the family’s plight. Share a photograph that you have cropped and say why you made that decision. Alternatively, post a photograph you have found and explain how the composition or cropping influences how you understand the image.

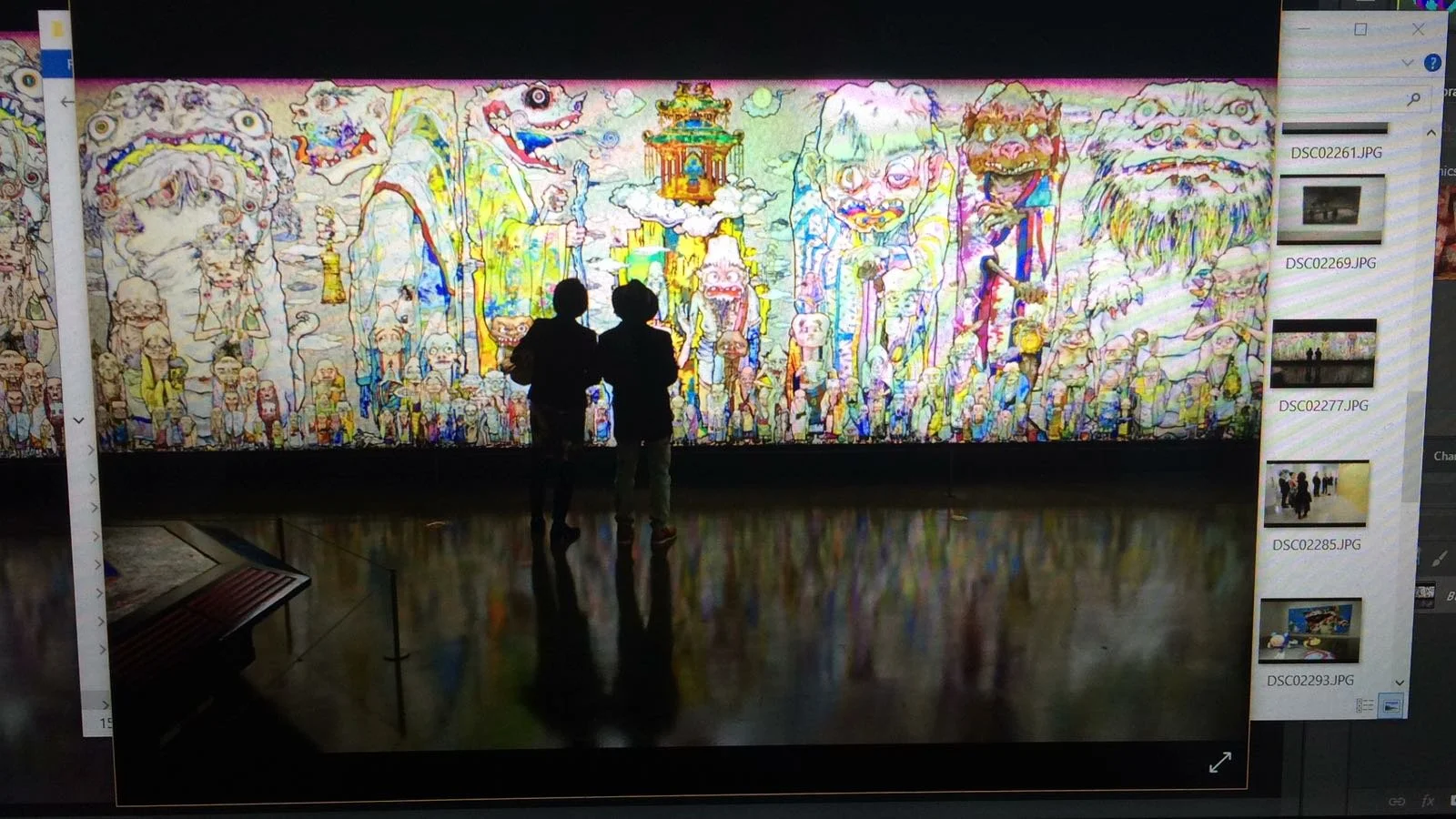

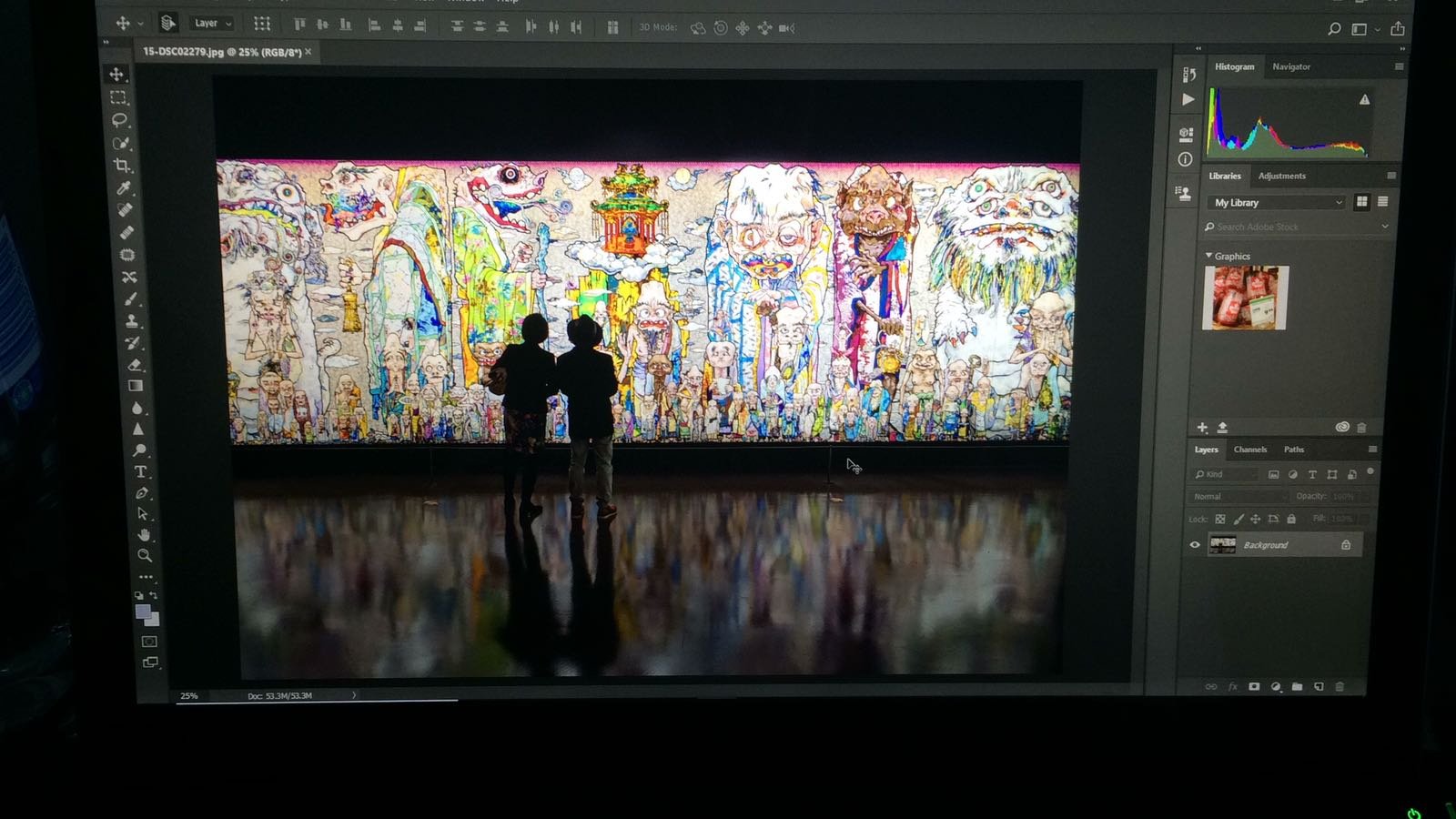

I took this photograph at the opening of an art exhibition featuring the work of Japanese artist Takashi Murakami held on February 2, 2018. I don’t usually crop my photos but did a specific crop available in Photoshop that let me ensure the main artwork was straight across the horizontal plane of the image. A more dramatic change had me using Photoshop’s clone stamp tool to remove the visual distraction of the base of a sculpture that protruded into the bottom left corner of the image. When I shot the image, I found there was no way to get the figures in the frame straight on without the base being visible, nor could I move further to the right without unwanted items on the right protruding into the image.

Overall, I think the image is stronger without the base being seen. I do wish I had stood further back though, so the couple’s shadow reflection on the floor was completely within the frame. A friend of mine, who is much stronger than I am with using Photoshop, suggested I remove the thin white line seen running along the bottom of the artwork. I ultimately chose to leave it in as it represents part of what’s in many galleries - a protective stanchion that keeps people from getting too close to the artwork. I also didn’t want to remove it because it reminds one that this is still an art gallery.

5.2.b. Creative Challenge: Words IN Pictures

Dorothea Lange and other FSA photographers understood how including signs, such as billboards and hand-painted notices, could help capture economic and social conditions. Take or share a photograph that includes words and explain how the words influence your understanding of the photograph.

This was a photo I took on March 7, 2023. I was attracted to the words “DREAM BIG” which I made the focus of the composition. It was spray painted on the door of an older strip mall, which has several empty shops and an abandoned movie theatre that shuttered during the pandemic. Along the back of this mall sits a relatively unused parking lot and a laneway. As such, it does have homeless people frequenting it, as the lot itself is somewhat hidden from the main roadway. The area is close to a major bus route, although buses don’t go past this specific spot. The overall area this small strip mall sits in is more of an upper class neighbourhood, so it can be odd to stumble onto this area as a lot of what surrounds it features newer pristine buildings.

I found it interesting that the words “DREAM BIG” are the most prominent words in the image. The graffiti tags above it are largely illegible to someone just passing by, which is okay, as the purpose of tags is for an artist to have their tags recognised by other artists in their area. A small election sticker is slapped above “DREAM BIG,” encouraging people to vote for anyone but Chesney, a local municipal council member. The door itself is interesting, it feels strong and tough, cemented in by the heavy bricks around it which make up the rest of the building. There are four locks on the door, two of which have rust forming on the edges. Ultimately, “DREAM BIG” feels like a message for the poor that frequent the area, and for those occupying the middle and upper class of the area, all of whom may be unhappy with the direction their lives have taken them.

From: December 23, 2019

When I started this course in December 2019, it had different reflective questions attached to some of the weekly units. The following are my responses to the original Week 03 questions attached to this course.

In what instances might we accept photographs as evidence or accurate records?

In this week’s slideshow it was noted how “Photographers often seek to capture a reliable view of the real world through a camera’s lens.” Ultimately, this quote emphasizes the idea that photographs can serve as objective documents of evidence and an accurate record of what has happened, as portrayed within the photograph itself. On the MoMA website, it is mentioned how “Photography is often perceived as an objective, and therefore unbiased, medium for documenting and preserving historic moments and national and world histories, and for visualizing and narrating news stories.” It also notes how photographs can “...bear witness to history and even serve as catalysts for change.” The MoMA overview also notes how these photographs can stir emotion in people, “foster sympathy,” and shed light on important issues, “...people, places and events.”

What makes photography’s relationship to truth so complicated?

Photography’s relationship to the truth is complicated for several reasons such as:

a photographer’s relationship to what they are photographing;

the decisions made about what photos are selected to be shown (either online, or in a magazine or in an exhibition) by a photographer, publisher / editor, or a curator;

the decisions made in how digital or analog editing by a photographer, photo curator and / or photo publisher; as well as

how shown photographs are discussed by viewers.

First, in terms of how the relationship between photography and the truth is complicated the unit’s slideshow does discuss how most photographers try to produce reliable images of the world they encounter. But this can be complicated, as the slideshow also noted how a photographer’s formal decisions impact the relationship the content of their photographs have with the context of the truth being presented, as: “...all photographs are necessarily shaped by how the photographer frames his or her subject, a process that introduces a personal point of view or perspective into even the most seemingly objective documentary photographs. Knowing this, some artists play with the notion of authenticity in their photographs.” Further to this, in the video interview with photographer Mike Mandel, Mandel discusses how people forget about the choices photographers make when he describes how: “The photograph is a complete abstraction… from the fact that we use different f-stops to create different depths of field, different illusions of motion. And different dark room capabilities of enhancing contrast, and all the things built into photography that people just totally ignore, and just read right through...”

Secondly, the decisions made about what photos are selected to be shown (either online, or in a magazine or in an exhibition) by a photographer, publisher / editor, or a curator can also impact how photography’s relationship to the truth is complicated. Maurice Berger, in her 2015 article for The New York Times, called “Gordon Park’s Harlem Argument,” explains how: “‘The Making of an Argument’ is an illuminating exercise in visual and racial literacy, investigating how words and images communicate multifaceted realities, convey points of view and biases, and sway or manipulate meaning” where “...the hundreds of photographs taken for the story were whittled down to the few published in Life, the editorial selection process, as Mr. Lord noted in his catalog essay, raised questions about authorship and meaning: ‘What was the intended argument? And whose argument was it?’ “ Ultimately, it seems reasonable to assume that the answers to these kinds of questions will shape the truths each viewer negotiates with the images.

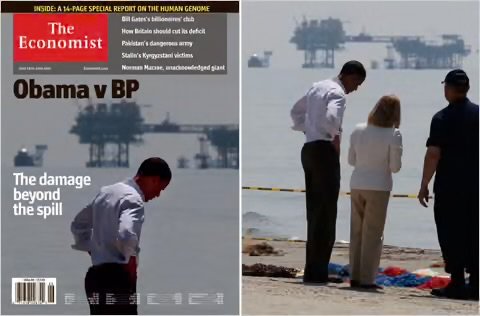

Thirdly, the decisions made in how digital or analog editing by a photographer, photo curator and / or photo publisher can impact the can impact photography’s relationship to truth. Today, using digital software tools such as Adobe Photoshop, it’s become ever increasingly simple to alter photos. If I had a dime for every time I’ve heard someone exclaim how “...that photo must have been Photoshopped,” I’d be able to buy a really nice dinner. Today, we live in a world where the noun ‘Photoshop’ has become an active verb and this undoubtedly has created a mistrust of photographs (and by extension, videos) as being representative of the truth. In this week’s slideshow, the discussion Carleton Watkins revealed how: “Watkins affixed to its mount a certificate vouching for the authenticity of its content.” Today, this doesn’t always happen. In photographer Ted Forbes’s 2015 YouTube vlog entry, “Photography: Truth or Beauty,” Forbes discusses the implications the Economist dealt with when it was revealed how their cover photo of President Obama was glaringly edited to remove several individuals. Forbes discusses how the impact of these changes to a Reuters image created a dramatic image that shows Obama “...staring down, pointedly deep in thought in front of the Gulf itself with an oil rig in the background.” Hany Farid, in his essay “Photo Forensics: From Stalin to Oprah” notes how dictators “...understood the power of photography. They understood that if you could remove someone from a photo, you could effectively remove them from history.” To this end, the individuals with Obama in the Reuters photo have effectively been removed from history. Following publication, Reuters ended up issuing a statement saying how they did not alter the photo, and that they did not support photo manipulation. Here is a screen capture of the Economist photo as compared with the Reuters original:

Photo > Greenslade, Roy. “Exposed - The Economist’s image of a lonely president who was not alone.” The Guardian, 06 Jul 2010.

And you can find Forbes’s video here:

Video > The Art of Photography. “Photography: Truth or Beauty.” YouTube, 19 Feb 2015.

The Guardian reported on this July 6, 2010 in an article titled “Exposed - The Economist’s image of a lonely president who was not alone.” And MotherJones has a good article from July 10, 2010 about this, titled: “Photoshopping the News.”

Today, truth in photography and the media in general has become even further complicated by the tribalism that has taken over politics, as exemplified (but certainly not limited to) by people such as American President Donald Trump who has declared the media to be ‘the enemy.’ But what’s interesting to note is how this has been an issue that photographers have struggled with for decades, and it’s one whose roots stretch farther back than the development of Photoshop. Handy Farid, in his 2015 article “Photo Forensics: From Stalin to Oprah” argues that “Photography lost its innocence almost at its inception.” For example, in this week’s slideshow discussion of photographer Gordon Parks, it is noted how: “Of the hundreds of images Parks took, Life’s editors chose 21, which they cropped, printed, and sequenced into a narrative emphasizing the drama and sensation of the conflicts. Many magazine photographers, including Parks, resented the way the meaning and interpretation of their work was skewed. In subsequent decades, they and other photographers who had largely depended on illustrated magazines for their livelihoods reclaimed editorial control of their images by publishing them elsewhere, without such manipulation.”

Finally, photography’s relationship to truth is also complicated by how photographs are discussed by artists and viewers. The introduction to this unit touches on this idea, saying how: “...text was called upon to shape viewers’ understanding of even seemingly straightforward pictures.” The introduction also stated how: “Today, photographers continue to use the camera as a means of documenting the world, acknowledging that their images are not fixed statements of fact but, rather, that they may be read and interpreted in many different ways.” In many ways, these readings and interpretations are the foundation for how photographs are discussed. As time moves forward, so to does the context of viewers who examine photographs, highlighting how images are interpreted and discussed can change over time. In “The Photographic Record” article on the MOMA website, it is noted how: “Many contemporary artists have taken on photographs and photographic archives as the subject of their own work, re-examining and re-interpreting the histories they convey through methods ranging from appropriation to digital manipulation of existing images. In doing so, they seek to reveal biases, challenge accepted histories, and construct new narratives.” Wang Ya Mu, in response to Hany Farid’s article “Photo Forensics” argues that: “Since image tampering is nothing new, it somehow creates a wide space for different readings for people with different political inclinations regarding “authenticity”... we have shifted from the paradigm of to-see-is-to-believe to believe-what-you-believe.”

In what ways do a photographer’s artistic choices and point of view affect the meaning of a picture?

In my answer to question two above, I quoted the introduction to this week’s slide show which described how every photograph is influenced by the formal decisions a photographer makes when composing and making an image. These choices can include in-camera choices that impact how the photo is framed and exposed; and the choices can also include post-processing decisions (whether they occur in the darkroom or on a computer), such as: how a photograph is printed in terms of contrast and filter choices, whether a negative or digital photo is cropped, or whether it is processed using traditional techniques or alternative techniques, as well as whether pictorial elements are added or removed.

The photographer also has influence over the content of their photographs in respect to the context in which it is created - both of which affect the meaning of the final image that is produced. This week’s slideshow revealed how the context that say Gary Winogrand brought to the decisions he made in selecting his subject matter of the everyday differed from the context that Carleton Watkins brought to his photographs that were designed to attract people to come purchase land in the American west. Both photographers brought very different contexts to the photographs they created, contexts which were impacted by the needs of their time, as well as the history of photography up until that point in their lives.

It’s interesting though how on the MoMA website’s discussion of Dorothea Lange’s photography, it has been noted that commissioned photographs can negatively taint how a photograph is considered, and that such photographs can even be viewed as examples of propaganda in support of a very specific agenda or point of view. To this, Lange argued that: “Everything is propaganda for what you believe in, actually, isn’t it? I don’t see that it could be otherwise. The harder and the more deeply you believe in anything, the more in a sense you’re a propagandist. Conviction, propaganda, faith.”

Finally, in moving beyond the focussed discussion of this week’s unit - I read how Pete Brook, in his article for Wired Magazine called, “Photographs are No longer Things, They’re Experiences” argues that today, in our immediate contemporary moment, “Photography is less about document or evidence and more about community and experience.” Brook interviews Stephen Mayes, director of “VII Photo Agency,” who argues that the move from analogue to digital photography marks a move from a fixed image to a fluid image, where: “Analog photography is all about the fixed image to the point that fixing is part of the vocabulary. The image doesn’t exist until it is fixed. It can be multiplied, reproduced and put in different contexts but it is still a fixed image. The digital image is entirely different: it is completely fluid. You think about dialing up the colour balance on the camera, there’s no point at which the image is fixed. More importantly than that, images now live in a digital environment. Given that an image is defined by its context it exists in a perpetually fluid environment in which the context is never fixed. Images’ meanings morph, move and can exist in multiple places and meanings at one time.” This clearly moves control of an image from that of the content producer photographer or publisher and into the hands of individual viewers.

Review…

Many photographers have used their cameras to take pictures that record, remember, or bear witness to both historical and personal events.

In publishing the guide Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843), Anna Atkins is considered to be:

The first female photographer; and

The first person to publish a book illustrated with photographs.

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandal’s Evidence seeks to explore the ways in which context influences our understanding of photographic images.

Dorothea Lange’s photograph, Migrant Mother (1936), was used to document and raise awareness of the impact of the Great Depression on families across the United States.

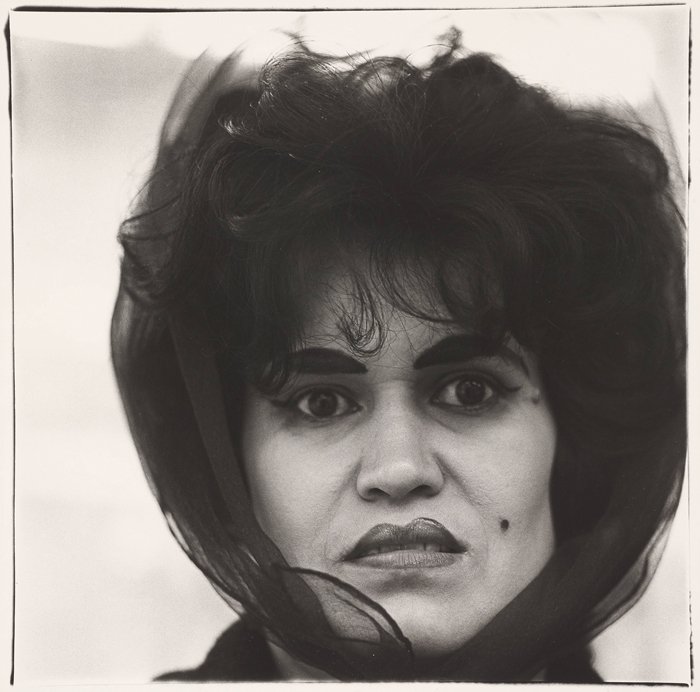

Opening in 1967 at the Museum of Modern Art, the exhibition New Documents presented the work of Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winograd, all known for working in the documentary mode to make personal statements.

The following statements are true about Gordon Parks and his photo essay “Harlem Gang Leaders”:

It was published in Life Magazine;

The series captured the life of Red Jackson, a leader of the Midtowners Gang; and

Many of the images are ambiguous in their meaning and subject to multiple interpretations.

Arthur Rothstein was criticized for staging their photographs and exaggerating experiences during the Great Depression.

Gauri Gill’s series, Acts of Appearance, was a collaborative project between the artist and her subjects.

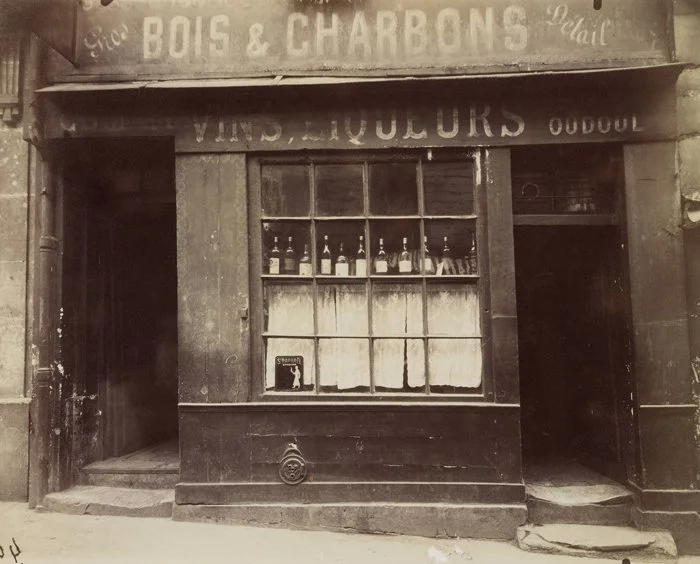

Eugene Atget made more than 10,000 pictures of Paris, France.

By the 1960s, many photographers began to feel constrained by the editorial control imposed by the popular press, including the editors of newspapers and magazines.

Anna Atkins. Aspidium Lobatium. 1853. Cyanotype (photogram), 12 3/4 × 8 5/8" (32.4 × 21.9 cm).

Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel. Evidence. 1977. Artists’ book. Publisher: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. © 1977, 2003 Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan. © 2003 D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc. All illustrations © 2003 Mike Mandel and/or Larry Sultan.

Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California. 1936. Gelatin silver print, 12 13/16 × 10 1/8" (32.6 × 25.8 cm).

Garry Winogrand. Central Park Zoo, New York City. 1967. Gelatin silver print, 8 7/8 × 13 3/8" (22.5 × 34 cm).

Lee Friedlander. New York City. 1962. Gelatin silver print, 5 1/4 × 8" (13.3 × 20.3 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Carl Jacobs Fund.

Diane Arbus. Puerto Rican Woman with Beauty Mark, New York City. 1965. Gelatin silver print, printed by Neil Selkirk, 14 11/16 × 14 5/8" (37.3 × 37.2 cm).

Gordon Parks. Harlem Gang Wars. 1948. Gelatin silver print, 10 15/16 × 10 1/2" (27.9 × 26.7 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Arthur Rothstein. Skull, Badlands, South Dakota. May 1936. Gelatin silver print, 7 3/8 × 7 1/2" (18.7 × 19 cm).

Gauri Gill. Untitled from the series Acts of Appearance. 2015–ongoing. Pigmented inkjet print, 28 × 41 15/16" (71.1 × 106.5 cm).

Eugène Atget. Boutique, 12 rue des Lyonnais. 1914. Albumen silver print, 6 7/8 × 8 11/16" (17.5 × 22 cm).